Fort Swatara, built in 1755 during the French and Indian War (1754-1763), guarded a natural passage in the Blue Mountains of Pennsylvania called Swatara Gap, about a mile north of Lickdale, then called Union Forge.

The garrison was also known as “Smith’s Fort” after Captain Frederick Smith, one of its commanding officers. It was part of a defensive chain of forts that extended throughout the frontier of Colonial Pennsylvania.

Fort Swatara was the only stronghold of its type, constructed and stationed by military troops, during the French and Indian War in what is now Lebanon County.

Additionally, there were more than 10 private fortified houses in the area including Light’s Fort in Lebanon, Fort Zeller near Newmanstown, the Isaac Meier Homestead in Myerstown and George Gloninger’s Fort in Pleasant Hill, which are often mentioned as places of refuge.

Read More: Light’s Fort a poster child for need of local historical preservation

Read More: The Isaac Meier Homestead: “The Old Fort” of Myerstown

Read More: The Heinrich Zeller House (Fort Zeller): Lebanon County’s secluded historical treasure

The French and Indian War

The French and Indian War was a conflict in North America between the colonies of Great Britain and those of France.

Although each side used Native American allies, British colonists called the conflict the French and Indian War, now its standard historical name. The conflict is viewed by many historians as the American theater of the Seven Years’ War (1756-1763), which spanned much of the globe.

In North America, it primarily was a dispute over the control of the upper Ohio River Valley, which included the strategic junction of the Allegheny and Monongahela rivers, the lucrative fur trade, and the location of several French forts, especially Fort Duquesne (present-day Pittsburgh).

The war started in May 1754 with the Battle of Jumonville Glen (in what is now Fayette County, Pennsylvania) as colonial Virginia militiamen and their Native American allies, commanded by 22-year-old Lt. Colonel George Washington, ambushed a French scouting party. Washington’s forces took 20 prisoners and killed and scalped 10, including French commander Coulon de Jumonville, who was tomahawked to death by a British ally, Mingo (Iroquoian) chief Tanacharison.

Washington then built and took post at Fort Necessity in anticipation of a French counterattack. The fort was poorly located, as it was surrounded by higher hills and woods, which made it vulnerable to enemy fire. Its design was also inadequate as it was not much more than a rudimentary wooden stockade surrounded by a ditch. Washington’s forces were reinforced with a company of 100 regular British infantry and additional militia troops from Virginia, bringing his forces at Fort Necessity to a total of 393 troops.

On July 3, 1754, as expected, the French retaliated in what is now known as the Battle of Fort Necessity. A unit of 600 French regulars and Canadian militia, with about 100 natives, overwhelmed Washington’s troops, killing 31 and wounding 70. Washington was forced to surrender (the only time he ever surrendered during his military career). The French destroyed and burnt Fort Necessity, and Washington and his surviving troops were released on parole and marched back to Virginia.

It became clear to Great Britain’s King George II that irregular colonial militia were no match for the highly trained French regular army. General Edward Braddock was ordered to seize Fort Duquesne and expel all French settlers and their allies from British territorial claims. On July 9, 1755, Braddock’s British Army unit was ambushed and decisively defeated at the Battle of Monongahela. Braddock was mortally wounded and died a few days later.

Over the following four years, the British suffered a string of defeats including the Battle of Fort Oswego (1756) and the Siege of Fort William Henry (1757) as French ground troops outmaneuvered and dominated British regulars and colonial militia.

Great Britain’s fortunes turned as British statesman William Pitt assumed control of the British war effort in North America. Pitt recruited experienced and qualified officers and convinced the British Parliament to invest heavily in gaining control of Great Britain’s territorial claims in North America.

The superiority of the British Royal Navy soon was evident as a series of naval victories and blockades cut off the majority of French supplies and troop reinforcements. The war was bankrupting France, and King Louis XV was scrambling to find resources to support it. French morale deteriorated as they were being defeated by British forces who had learned successful frontier war tactics.

Several major British military victories including the capture of Louisbourg and Fort Duquesne (1758), the Battle of Quebec (1759), and the French surrender of Montreal (1760), which was the final battle of the war in the North America, led the way towards a British victory.

The French and Indian War officially ended, along with the Seven Years’ War, with the signing of the Treaty of Paris on Feb. 10, 1763. It propelled Great Britain into the dominating European power in North America. However, British policies of imposing taxes on North American colonists to help pay for the enormously expensive war were a leading cause of social discontent and a major factor in starting the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783).

Why a Military Garrison at Swatara Gap?

In the years leading up to the French and Indian War, the relationship between Native Indians and European settlers were generally peaceful in the Pennsylvania colony. However, the onslaught of the war sparked a series of raids on Pennsylvania frontier settlements by Indians allied with the French. On Oct. 16, 1755, the Penn’s Creek massacre occurred near present-day Selinsgrove, in which members of the Lenape tribe killed 14, kidnapped 11 and wounded one man who managed to escape and tell the story.

Swatara Gap, being a natural passage in the Blue Mountains of Pennsylvania, was an area through which marauding Indians launched several attacks against frontier settlers. In 1755, Peter Hedrick and other local Swatara Gap area settlers defended themselves as they fortified Hedrick’s log-walled farmstead and surrounded it with a rudimentary log stockade.

In 1756, Benjamin Franklin persuaded Robert Hunter Morris, deputy governor of Colonial Pennsylvania, and the Provincial Council to establish an armed military force and build a chain of forts to protect the frontier settlements. Franklin and Lt. Colonel Conrad Weiser, First Battalion of the Pennsylvania Regiment, were appointed to direct the construction of the series of forts between the Delaware and Susquehanna rivers. Swatara Gap was identified as an area where one of these forts was to be built.

Fort Swatara as an Active Garrison

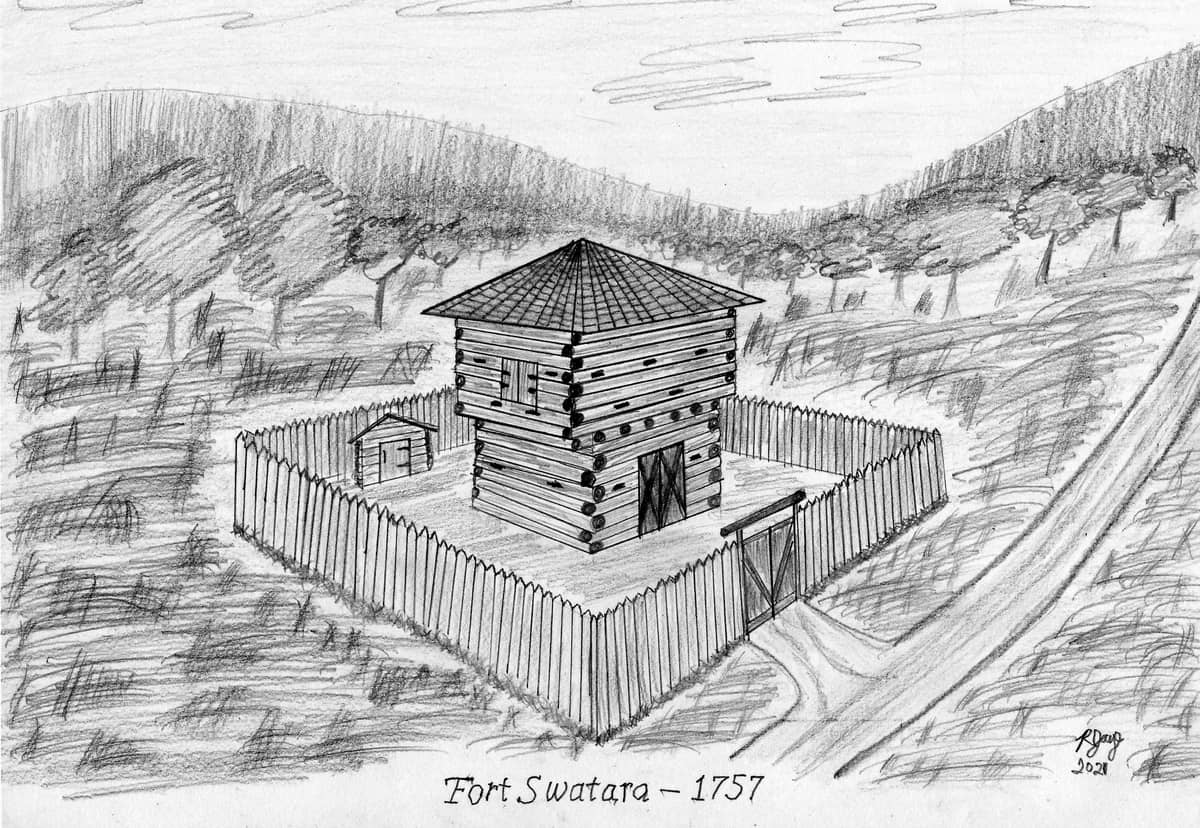

On Jan. 25, 1756, Capt. Frederick Smith and a company of 50 men received orders from the deputy governor of Colonial Pennsylvania to take posts at Swatara Gap. Smith’s orders were to either occupy and reinforce the existing Hedrick stockade or build a new fort. It is believed that the troops quickly built Fort Swatara by erecting a log blockhouse and magazine shed for ammunition storage surrounded by a sturdy log stockade.

Smith was paid 165 British pounds sterling for the work completed at Fort Swatara.

In the summer of 1756, two settlers were killed by marauding Indians near Fort Swatara, prompting Weiser to order Smith to send eight troops to protect settlers as they worked in their fields, eight to patrol the area west of the fort and 16 to guard settlers near the fort, and to deploy 21 troops to occupy nearby Fort Manada.

In August 1756, several Indian attacks near Fort Swatara resulted in the death of one settler, two of Smith’s troops and three child kidnappings within two miles of the fort. Several other settlers were killed by Indians as they were relocating from the area.

In the fall of that year, William Denny, the new deputy governor of Colonial Pennsylvania, sent Smith and some of his troops to assist in the defense of Fort Augusta, a stronghold in what is now Sunbury, despite the ongoing Indian attacks near Fort Swatara. In Smith’s absence, Capt. Christian Bussey was placed in command of Fort Swatara. Smith returned to Fort Swatara at the end of spring 1757 to find his outpost depleted of troops, as many had been deployed elsewhere.

Smith came under scrutiny for his harsh treatment of officers, poor record-keeping and inadequate communication with his superiors. He was abruptly replaced by Lt. Phillip Martzloff.

Fort Swatara was still lacking a sufficient number of troops as Indian attacks continued. In August 1757, Indians killed five local settlers (two of whom were brothers), kidnapped a mother and child, and wounded a soldier. Martzloff’s leadership was soon criticized by his troops and he was ordered to report to another fort for reassignment. Samuel Weiser, Conrad Weiser’s son, temporarily commanded Fort Swatara in Martzloff’s absence. In February 1758, upon Martzloff’s return to Fort Swatara, the deputy governor of Colonial Pennsylvania ordered him replaced by Lt. Samuel Allen.

Fort Swatara’s command issues continued as a visiting officer reported that Allen’s inventory was lacking items such as serviceable arms, kettles, blankets, powder horns, tomahawks and provisional tools. The inadequate number of troops and lack of various supplies at Fort Swatara certainly did not help matters during new Indian raids in the Blue Mountains during April 1758. These raids resulted in the death of four more settlers and a kidnapped woman near Fort Swatara.

By mid-1758, the British were gaining control of the French and Indian War, and Indian attacks in the Blue Mountains were subsiding. Richard Peters, provincial secretary, ordered the troops stationed at Fort Swatara and other frontier forts along the Blue Mountains to join British military units as they advanced on major French outposts. Fort Swatara was abandoned and never used again for military purposes.

Marking the Fort’s Location

In July 1932, officials from the Lebanon County Historical Society finalized arrangements for the dedication of two boulders with copper plates to designate the location of Fort Swatara.

The smaller boulder stands in a field where the fort actually stood, and the larger one stands along the roadside not far from the fort’s site.

The epitaph on the larger boulder’s plate reads: “Fort Swatara of the French and Indian War. Erected in the fall of 1755. It stood 500 feet south of this spot, directly north of the run of water flowing east and west. Commanded by Capt. Frederick Smith, of Chester County, of the First Battalion of the Pennsylvania Provincial Regiment, Lieut. Colonel Conrad Weiser commanding. Finally abandoned in 1758, Capt.-Lieut. Samuel Allen in command. It consisted of a block house pierced for musketry fire and surrounded by a stockade. This boulder tablet placed by the Lebanon County Historical Society. Capt. H.M.M. Richards, President.”

A Pennsylvania Historical Marker

On July 14, 1999, a roadside Pennsylvania Historical Marker for Fort Swatara was dedicated along state Route 72 about a mile north of Lickdale.

It reads: “Fort Swatara – Originally built by Peter Hedrick, 1755. The stockaded blockhouse was improved in early 1756 by Capt. Frederick Smith to guard Swatara Gap and protect the frontier settlements. Site is on Fort Swatara Drive about a half a mile from this intersection.”

Fort Swatara’s Legacy

There were no major battles near Fort Swatara; however, several soldiers and many settlers were killed (including a pregnant woman who was found mutilated and scalped), and several women and children were kidnapped during raids by marauding Indians. Fort Swatara did prevent Indian raids from progressing to the more populated communities in what is now Lebanon County.

After the colonial Pennsylvania militia forces abandoned Fort Swatara in 1758, local settlers probably dismantled the structure and used its logs and other building materials to construct or renovate homesteads or farmsteads in the area. No physical remnants of Fort Swatara survive above ground today.

Fort Swatara was the last of the chain of French and Indian War forts along the Blue Mountains of Pennsylvania to be marked with a permanent memorial, but has since taken its place among other garrisons of importance in the history of colonial Pennsylvania.

Questions about this story? Suggestions for a future LebTown article? Reach our newsroom using this contact form and we’ll do our best to get back to you.

Build the future of local news.

Cancel anytime.

Monthly Subscription

🌟 Annual Subscription

- Still no paywall!

- Fewer ads

- Exclusive events and emails

- All monthly benefits

- Most popular option

- Make a bigger impact

Already a member? Log in here to hide these messages

You know us because we live here too. LebTown’s credibility comes from showing up, listening, and reporting on Lebanon County with care and accuracy. Support your neighbors in the newsroom with a monthly or annual membership, or make a one-time contribution. Cancel anytime.