Justin Bollinger remembers stories about how difficult it was for his grandfather to lose the family farm through eminent domain proceedings to build Middle Creek Wildlife Preserve in 1970.

“It was really tough for my grandfather because he was born and raised in the farm home and he worked on the farm that the family lost,” Justin said about his grandfather, Paul Bollinger. “We would often drive through the ‘project,’ which is what he called it because it was named Project 70. We’d drive around and he’d point out where the buildings and fields were for our farm and neighboring farms.

“That was hard because they had a life there and when you talk about all of their neighbors, that meant they also had a community — an entire rural community that was displaced.”

In September 1970, Paul and Justin’s grandmother, Ethel, purchased a new farm: 113 acres located in the 700 block of State Route 419 near Myerstown. It’s a farm the family has owned for 52 years and, thanks to the recent placement of their property into the county’s farmland preservation program – for perpetuity.

The addition of the Bollinger Family Farm into Lebanon County’s farmland preservation program is a historic event: it signified 20,000 acres preserved since the first farm in Heidelberg Township, which consists of 91 acres, was placed into the program 30 years ago in 1992.

Justin said his wife Rebekah and his parents Donald and Sharon Bollinger made the decision to place their farm into the farmland preservation program for aesthetic and economic reasons.

“It is important to us to maintain these spaces to grow food locally and to secure the local food chain but to also preserve a way of life in our communities,” said Justin, who lives with his family on the farm and rents the land to two neighboring farmers. “Agriculture is the backbone of the economy in our local communities.”

Curtis Martin, vice chairman of the Lebanon County Agricultural Land Preservation Board (LCALPB), said 179 easements totaling 19,996 acres in Lebanon County are in the county program, which was created statewide in 1981 with passage of the Pennsylvania Agricultural Land Preservation Program (Act 43).

Before a farm can enter the preservation program, however, it has to be participating in an Agricultural Security Area, according to Martin.

“ASAs are driven by landowners that have 250 contiguous acres and those individuals can apply for an ASA, which helps prevent condemnation of their land,” said Martin, a 10-year board member who preserved his South Annville farm in 2009. “If land that is in an ASA happens to be condemned, the condemnation has to go through a review process.”

The statewide ag preservation program began to gain steam in 1987 with Pennsylvania voter approval of a $100 million bond referendum to establish a funding source, but some of that momentum was lost due to farmers who were initially leery of participating in a program they knew little about.

“I know there was some resistance to entering the program,” Martin recalled. “Conservative Amish and Mennonite communities did not want to participate in it, so they created the Lancaster Farmland Trust, a very similar program. There was also fear of how much control farmers might give up by participating in the program.”

Another major sticking point in Lebanon County was the Clean and Green Act – a 1974 law enacted to implement the constitutional amendment to preserve farmland through preferential property tax assessments. The issue with entry into Clean and Green was the requirement that a farm had to be reassessed to enter the program.

“There was a lot of resistance to reassessment,” said Martin. “The previous assessment was bringing in farmland at a lower evaluation than the Clean and Green would have brought into it, so farmers resisted entering Clean and Green.”

By 1989, Lebanon County Commissioners helped to initiate participation by approving a resolution to appropriate $50,000 for fiscal year 1990 for the purchase of agricultural easements. In 1991, the county commissioners established LCALPB and the board received 12 applications that same year – of which nine were approved for agricultural preservation easements (ACE), according to a timeline of significant preservation events in Lebanon County.

Aside from the initial resistance, another issue was how to fund the program. The state began in 1993 to collect a two-cent per pack tax on cigarette purchases to fund ACEs, an initiative that generates over $20 million annually for agricultural land preservation.

Funding the initiative has always been a concern. In fact, another 34 farms totalling over 3,660 acres wait to be preserved in Lebanon County, but a shortfall in funding prevents that from happening.

“We have eight farms in the process of being preserved and another 28 applicant farms,” said Martin. “Those applicant farms are those who are on a waiting list. We need $7 million to cover all the farms that are approved but are on the waiting list.”

The $1.5 million raised for ag preservation in 2022 pales in comparison to the financial need.

Funding comes from local municipalities who make annual contributions and Lebanon County, which also provides administrative services, according to Martin. Other funding sources include private donations and monies received locally via the Marcellus Shale fund.

The county gained $177,000 last year for land that was removed from Clean and Green. Property owners must pay back the difference in what they paid in taxes while being in the program and what they would have owed for the previous seven years plus 6 percent interest for land that’s removed from Clean and Green.

“The state matches our county contribution at a rate of $1.40 for every dollar we raise,” added Martin. “We had raised locally in the neighborhood of around $700,000 to $800,000 in 2022 from various sources.”

The statewide program, which surpassed 600,000 acres preserved in 2021, had received an infusion of funding in 1999 when the state created its Growing Greener program, which included an additional $100 million in commonwealth funding for farmland preservation efforts. In 2005, $80 million was added via the state’s Growing Greener II initiative.

The added funding in 2005 helped the county’s program achieve a record year in 2006 of preserving farmland with 16 farms and 2,312 acres preserved in perpetuity.

“It was a record year because that’s when the bond issue monies were available after multiple bond issues were approved,” added Martin.

For Justin Bollinger, entry into the program not only preserves his grandfather’s farm but the legacy of the family who originally settled the land over 300 years ago.

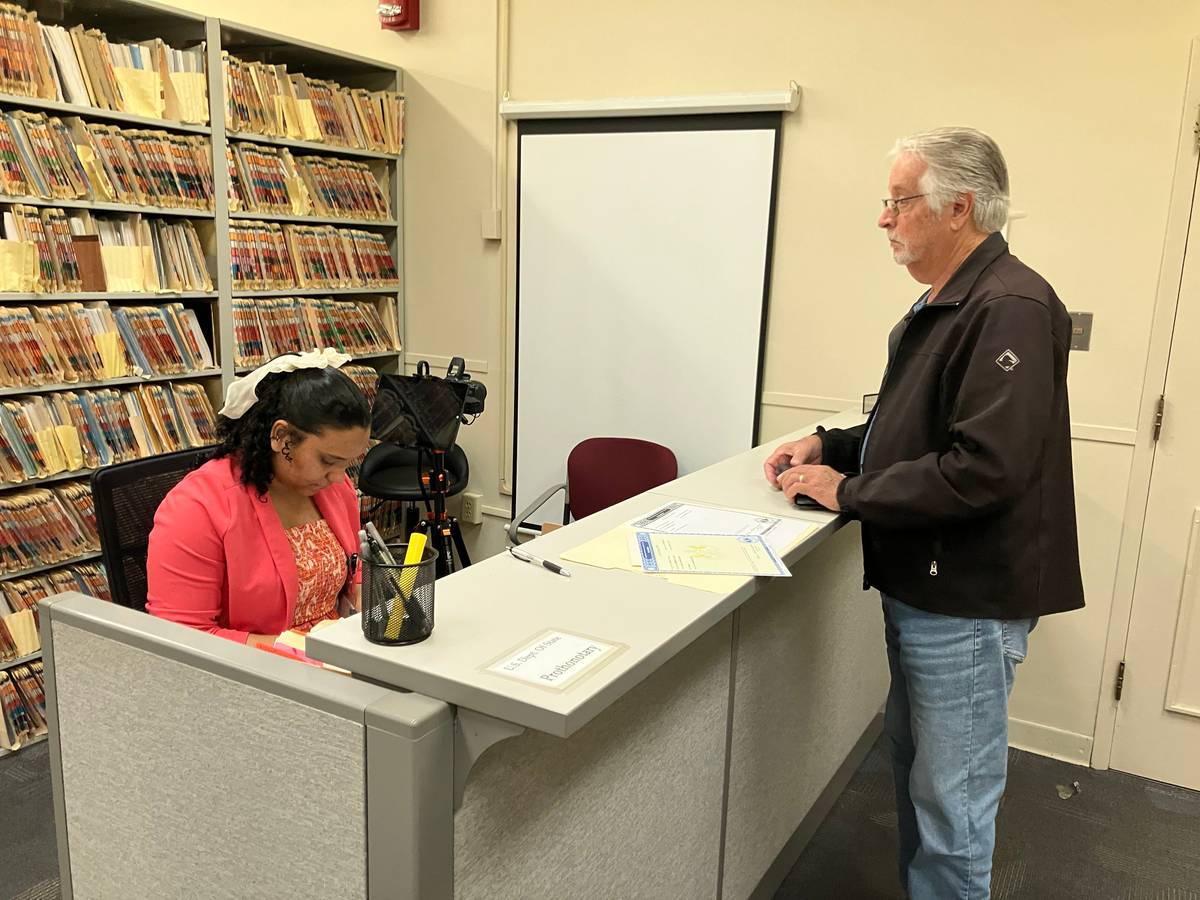

“A unique aspect of the property is that we had the opportunity to get to know the ninth- or tenth-generation family member whose ancestor owned the farm in 1720,” said Bollinger, who met Greg and Keely Moyer at a recent celebration of 30 years and 20,000 acres preserved in Lebanon County. “Their ancestor was a German immigrant who came from the Schoharie region of New York and who made their way down the Susquehanna River, possibly as part of Conrad Weiser’s group.”

Bollinger said the Moyers were happy to be invited to the dedication ceremony, and said Greg told him that his genealogical research indicates that the Heinrich Meier (German) Moyer (English) family owned the farm for the first 150 to 160 years.

“It was special for them since he (Greg) has an interest in family genealogical history,” added Justin. “They were happy to know that the (Moyer) farm will always remain a farm. ‘It’s been 300 years since the farm was settled,’ Greg said to me, ‘and you are preserving it, which is a really special thing.’”

Over 300 years after the farm was first established, Justin enjoys the time he spends on the farm with his wife and children.

“It means a lot to be able to sit outside at the farm with my wife and kids and we’re really blessed to live in such a beautiful area and to reminisce about the memories I have of how we got the farm to where it is today,” said Justin.

“It is rewarding, and gratifying and humbling to know that we – Rebecca and I – are a part of stewarding this land for future generations. When you are charged with being responsible for a farm. It really makes you take root in a place, which I think gives you stability and is healthy for the good of the local community.”

Questions about this story? Suggestions for a future LebTown article? Reach our newsroom using this contact form and we’ll do our best to get back to you.

Be part of Lebanon County’s story.

Cancel anytime.

Monthly Subscription

🌟 Annual Subscription

- Still no paywall!

- Fewer ads

- Exclusive events and emails

- All monthly benefits

- Most popular option

- Make a bigger impact

Already a member? Log in here to hide these messages

Trustworthy local news is built on facts. As Lebanon County’s independent news source, LebTown is committed to providing timely, accurate, fact-based coverage that matters to you. Support our mission with a monthly or annual membership, or make a one-time contribution. Cancel anytime.