The midterm elections could loosen marijuana restrictions in the United States, as four states put ballot initiatives on legalization to a vote.

Voters in Utah and Missouri will choose whether patients should gain access to medical marijuana.

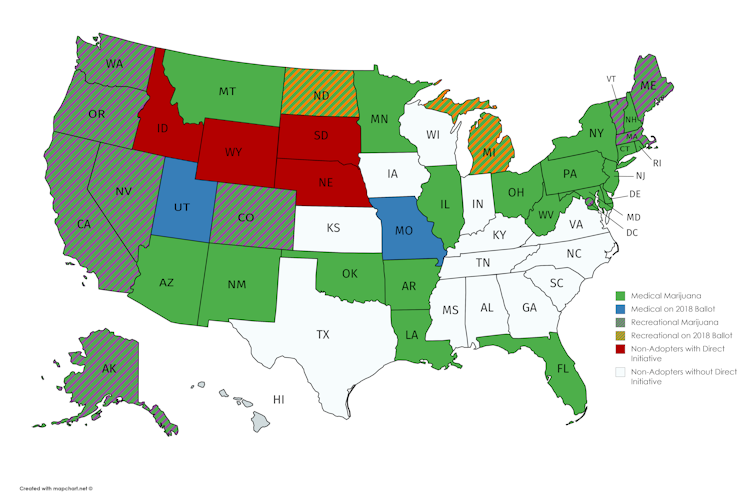

In Michigan and North Dakota, where medical marijuana is already legal, residents will decide whether to allow it for recreational use. If so, they would join nine U.S. states, Washington, D.C., Canada and Uruguay in launching a regulated recreational marijuana market.

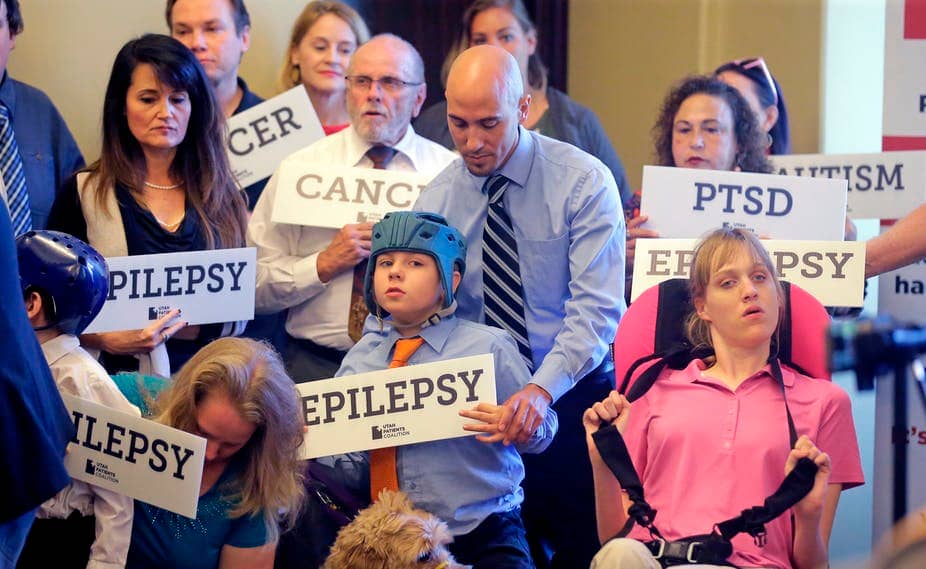

Another 22 American states have adopted comprehensive medical marijuana programs since 1996, when California became the first to recognize the medicinal uses of marijuana in easing the symptoms of serious illnesses like HIV, cancer, epilepsy, PTSD and glaucoma. Recently, marijuana’s potential value for treating chronic pain has garnered attention as an alternative to opioids.

No tipping point

Support for marijuana legalization has never been stronger in the United States.

Seventy-two percent of Democrats and a narrow majority of Republicans – 51 percent – support legalization, according to Gallup.

Polling suggests that the upcoming marijuana initiatives in Michigan, Utah and Missouri will pass, while legalizing marijuana seems less likely in conservative North Dakota.

Strong public support and successive waves of state-level legalization in election years has led many policy analysts to argue that marijuana has reached a tipping point in the United States.

Two-thirds of all U.S. states will likely have some kind of legal marijuana by the end of this year. After that, the argument goes, its nationwide expansion is inevitable.

As marijuana policy researchers, we question that narrative.

Our research indicates that medical marijuana progress may well stall after this latest round of ballot initiatives. Recreational marijuana may continue to expand into states with legal medical marijuana but will ultimately hit a wall, too.

The reason for our caution has to do with the particular way marijuana legalization has occurred in the United States: at the ballot box.

Ballot initiatives have power

So far, every recreational marijuana law passed has occurred via ballot initiative, not through the state legislative process. Seven of the first eight medical marijuana laws – those in California, Alaska, Oregon, Washington, Maine and Nevada – were also adopted via ballot initiative.

Such direct initiatives – where citizens can put a policy on the ballot for approval – are a powerful, if nontraditional, form of policymaking in the United States.

Rather than relying on lawmakers to write and pass legislation on certain issues – often, controversial ones – ballot initiatives harness public opinion. They have been used to legalize or restrict same-sex marriage, place limitations on taxing and spending, raise the minimum wage and much more. Some are funded by wealthy individuals with specific business interests.

Even in states where ballot initiatives have little hope of passing, they can be an important force for policy change.

In Ohio, marijuana advocates in 2015 spent over US$20 million in an effort to legalize both medical and recreational marijuana in the same ballot initiative. Ohio voters overwhelmingly said no – but the campaign revealed broad support for a medical marijuana policy.

The Marijuana Policy Project, an advocacy organization, said it would put medical marijuana on Ohio’s ballot in 2016. In response, Ohio’s legislature moved quickly to craft and pass its own medical marijuana legislation.

Something similar may happen in Utah this fall. Gov. Gary Herbert opposes the expansive medical marijuana ballot initiative up for vote in his state but would support a more restrictive medical marijuana program.

Herbert says he will call a special session of the legislature to work on medical marijuana regardless of whether it succeeds at the ballot. Lawmakers are already working on compromise legislation that would be acceptable to conservative state legislators and the influential Mormon Church.

The limits of direct initiative

So the ballot initiative is powerful. But our analysis suggests its potential for liberalizing marijuana access in the U.S. is nearly tapped out.

Of the 19 U.S. states that have no form of legal marijuana, only six – Idaho, Wyoming, South Dakota, Nebraska, Utah and Missouri – allow for direct initiatives.

The remaining 13 states without legal marijuana are mostly conservative places like South Carolina and Alabama, where legislatures have indicated reluctance to loosen restrictions. If voters there wanted medical or recreational marijuana, they would not have the option of bypassing policymakers to get the issue on the ballot.

Marijuana legalization won’t end with the 2018 midterms. There is still room for recreational marijuana to expand into the 22 states that currently have legal medicinal marijuana.

History shows that once people grow comfortable with medical marijuana – seeing its impacts on patients and tax revenues – full legalization often follows.

In our analysis, the remaining 13 states are very unlikely to liberalize access to marijuana without a significant push by the federal government.

That’s unlikely, but not impossible, under the Trump administration.

Federal law still considers marijuana an illegal Schedule I drug under the Controlled Substances Act, meaning that, as far as the U.S. government is concerned, the plant has no medical value.

The Obama administration took a hands-off approach to states’ legalization, allowing them to experiment. But Attorney General Jeff Sessions has directed Justice Department attorneys to fully enforce federal law in legal-marijuana states.

Quietly, however, the Trump administration has also sought public comments on reclassifying marijuana. And the president himself has at times signaled support for leaving marijuana up to the states.

If Sessions leaves the Trump administration, as rumor has long suggested, the DOJ’s position on marijuana enforcement could change.

Democrats have indicated that if they win back one or both houses of Congress on Nov. 6, they could push to remove marijuana as a Schedule I drug as soon as next year.

Democrats have indicated that if they win back one or both houses of Congress on Nov. 6, they could push to remove marijuana as a Schedule I drug as soon as next year.

Daniel J. Mallinson Assistant Professor of Public Policy and Administration, School of Public Affairs, Pennsylvania State University

Lee Hannah Assistant Professor, Wright State University

This column was originally published by The Conversation and is republished here with permission.