The physical scale of the canal planned by the Schuylkill and Susquehanna Navigation Company appears gargantuan even to our modern eyes.

In its original plan, the waterway would see goods enter at the Delaware River just north of where the Ben Franklin Bridge stands today, and then travel through the system: Across Philadelphia, over the falls of the Schuylkill, and lastly jumping from the Tulpehocken to the Quittie to the Susquehanna through an epic series of summit-crossing canals.

With roots in early expansionist dreams of William Penn, the canal system was capitalized by Robert Morris, a signer of the Declaration and financier of the revolution (and owner of what would become the President’s House in Philadelphia).

The dream would never be fully realized though, and the canal system would not come close to providing an economic boon like Pennsylvania’s northern neighbors had seen with the Erie Canal. The failure would contribute to Morris’ downfall which saw him remanded to debtors’ prison for a period and then dying in financial destitution with no public ceremonies to mark his passing.

The canal’s construction also stoked the flames of one of the lesser-known flareups in Pennsylvania labor history, the Myerstown Christmas riot. As Lebanon County Historical Society archivist Adam Bentz told the Reading Eagle, “It’s not one of the more well-known events of the past.”

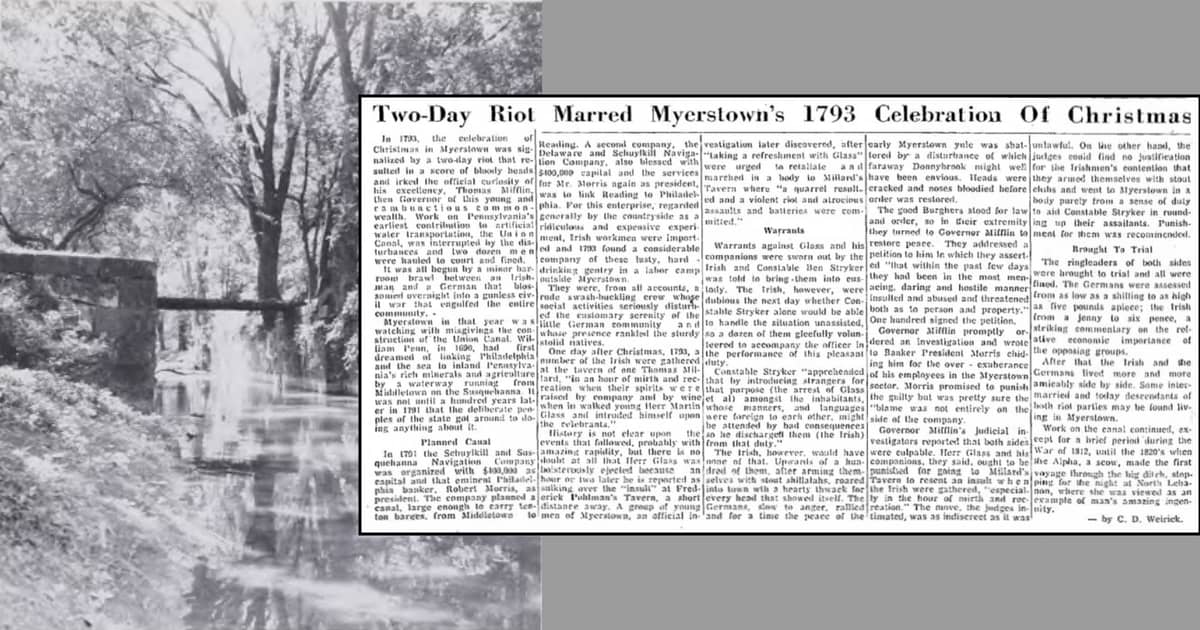

A 1955 article by Lebanon lawyer and amateur historian C.D. Weirick explains that even in the canal’s preliminary stages, the canal system was viewed with skepticism locally:

For this (canal) enterprise, regarded generally by the countryside as a ridiculous and expensive experiment, Irish workmen were imported and 1793 found a considerable company of these lusty, hard-drinking gentry in a labor camp outside Myerstown.

The Berks History Center writes that further bad blood developed as the local Pennsylvania Germans and temporary Irish/Scotch-Irish residents saw each other’s cultures as unfamiliar and crude, and in all likelihood neither community was very welcoming to the other.

It probably didn’t help that there was plenty of good whiskey available locally, as over the Christmas holiday in 1793, the underlying tensions combined with the holiday spirit(s) led to a flareup that would catch the attention of the very highest powers in Pennsylvania.

Picture this: Two taverns serving two different communities who viewed each other with skepticism if not outright hostility. The canalmen were at Thomas Millard’s tavern; the Pennsylvania Dutch at Frederik Pohlman’s.

According to the Weirick account, the fight began when Martin Glass stopped by Millard’s, where he was “boisterously ejected” in an insulting way, an offense which Glass took to Pohlman’s Tavern where his story was met with sympathetic ears. The local crew “marched in a body to Millard’s Tavern where ‘a quarrel resulted an a violent riot and atrocious assaults and batteries were committed.'”

The Berks History Museum notes that the 12 in Glass’s party got the better of the 8 Irishmen assembled at Millard’s.

The next day the canal people arranged for the arrest of Glass’s crew through local constable Captain John Benjamin Spyker (Speicher), a neighbor and friend of Conrad Weiser. Spyker attempted to dissuade the “dozen” of gleeful Irish volunteers who showed up to accompany him in serving the warrant, but his efforts only seemed to intensify the gathering.

Again from Weirick’s account:

Upwards of a hundred of them, after arming themselves with stout shillalahs (wooden clubs), roared into town with a hearty thwack for every head that showed itself. The Germans, slow to anger, rallied and for a time the peace of the early Myerstown yule was shattered by a disturbance of which faraway Donnybrook might well have been envious. Heads were cracked and noses bloodied before order was restored.

The townspeople addressed their concerns in a letter to Governor Thomas Mifflin, another of Pennsylvania’s leading men throughout the Colonial period. Governor Mifflin ordered an investigation that reported culpability on both sides. Gov. Mifflin also wrote to Morris “chiding him for the over-exuberance of his employees in the Myerstown sector.”

In the trials that followed, the Germans ending up getting the higher assessment having first instigated the physical confrontation, with fines ranging from a shilling to five pounds. The Irish saw assessments ranging from a “jenny to a six pence”. These fees were minor compared to what the town saw in property damage, according to the Reading Eagle’s article which cites court records that show more than 11,000 pounds in property damage.

Participants

Natives: Martin Glass, John Weiss, Martin Heffelinger, Jacob Grove (Groff), Jonas Eckert, Phillip Lootz (Lutz), Henry Blecker, Adam Kassert, George Weirick, George Sinkle

Canal Men: Samuel Galbreath, Joseph Long, John Scott, Neal McHugh, John Fletcher, James Rennals, Robert Galbreath, John Quigley, Daniel O’Boyd, Patrick McHenry

Canal construction wouldn’t complete for another 35 years, with the final push coming through a newer Union Canal Company made briefly more profitable as anthracite coal became America’s new emergent power source (alas, railroads would soon displace canals as the dominant transportation system). In total eight canal locks would be constructed in the Myerstown area.

Weirick writes that after the incident, the Irish and Germans “lived more and more amicably side by side” with some even intermarrying, and residents from both parties remained in Myerstown even in his day (the fifties). Is there any more local lore or family tradition floating around out there? Let me know in the comments!