Cumberland Street is at the heart of both Lebanon and a long-running debate over whether it should remain, as it has for decades, a one-way street.

A mid-century decision to split the traffic on Cumberland Street, part of Route 422, into separate westbound and eastbound roads has been questioned by various groups over the years.

Today, westbound traffic from Route 422 continues along Cumberland, which becomes one-way at N. 8th Avenue before reverting back to two-way at N. 12th Street. Eastbound traffic turns onto the parallel Walnut Street several blocks to the south. The Cumberland section runs through Lebanon’s business and culture hub, otherwise known as the downtown.

Most concerns about the street have been voiced by various business interests over the years. A mid-1980’s campaign known as the Willow Street Bypass Project, which would have made Cumberland two-way and converted nearby Willow Street to a westbound-only street, gained steam for several years, before being dropped in 1986 for a number of reasons, including a lack of resources and controversy, among others.

Recently, there has been renewed interest in similar plans, which aim to direct more activity into downtown businesses.

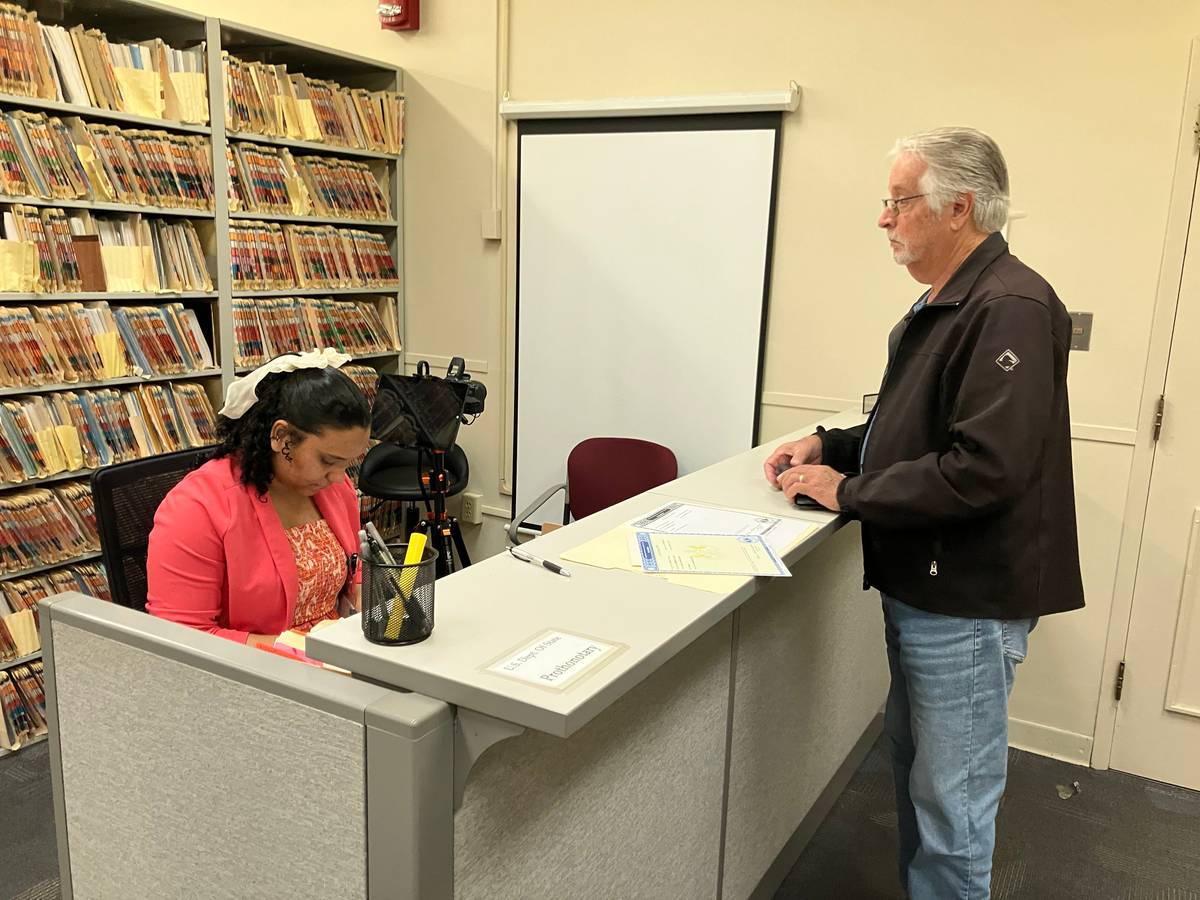

Jonathan Fitzkee and Song Kim of the Lebanon County Planning Department sat down with LebTown to explain the considerations that go into decisions like this and why a two-way Cumberland may not be an effective solution for Lebanon’s businesses and downtown.

Kim has been a Transportation Planner for 3 years, though before becoming a planner he served for 12 years as the department’s Zoning Administrator. Fitzkee, in addition to being the Senior Transportation Planner, also serves as the Assistant Director. He has been a planner for 16 years.

The Origins of the One-Way System

The City of Lebanon owns the major roads within its limits. It’s also a city at the crossroads of two major county arteries, Routes 72 and 422.

Lebanon’s unusual circumstances have necessitated a web of one-way streets and alleys-cum-roads that may seem convoluted, even intentionally disorienting to the outsider. But making the decision to keep a road one-way, let alone many, is not something taken lightly by transportation planners.

“When you make changes to a major roadway like 422, you’re not just affecting the downtown in Lebanon,” said Fitzkee. “You’re also affecting other towns, roads, and traffic along that route, potentially even beyond the county.”

“Who do we grant that power?”

This question is partly rhetorical. The Lebanon County Metropolitan Planning Organization (MPO), which Fitzkee and Kim serve as technical and support staff, works with local governments like the City of Lebanon, as well as the Pennsylvania Department of Transportation (PennDOT), the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA), and the Federal Transit Administration (FTA), to manage Lebanon’s transportation network.

In fact, the MPO is an organization created through agreements among the above entities to “conduct a continuing, comprehensive and cooperative process for transportation planning, programming and decision-making,” according to their website. The full 2019 staff list of the MPO may be viewed here (PDF).

The Cumberland decision is one that had been discussed as early as 1954, as a Lebanon Daily News (LDN) article at the time mentions. In the first discussions of the one-way street system, Chestnut Street, not Walnut Street, was proposed as Cumberland’s eastbound counterpart. Walnut Street, however, was the final recommendation, due to its width. The project began its trial period in mid-1957 and was officially put into place on November 25 of that year, according to a contemporaneous LDN story. Extensions to the system were added in following years.

Lebanon’s switch to a one-way system was not unusual for the time. A number of towns across Cold-War-era America converted former two-way streets to one for a variety of reasons, including greater efficiency, higher speeds, and evacuation capabilities in the event of an act of war.

“Everything you do has a ripple effect,” explained Fitzkee. For this reason, it can be difficult for institutions to effectively communicate why changes are being done. The MPO has gotten complaints from the public about changes that, in Fitzkee and Kim’s eyes, were clear improvements.

Some factors are more important than others, though. “Safety is always, always the main priority,” said both Fitzkee and Kim. Beyond safety, the concerns include resources, congestion, and even (perhaps surprisingly) community, including business development.

Resources

“We receive around 10 to 12 million dollars in funding annually,” said Fitzkee; around two dozen different state and federal sources provide these funds for use in projects. “That money gets pulled in a million different directions.”

Though it may seem like plenty, the various provisions that funding comes with means that projects from all over the county must comply with conditions set by the government institutions that provided the funds in the first place. To better understand the complex system of transportation funding, visit the webpage detailing the current federal transportation bill, the FAST Act.

Even now, there is a four-phase 422 and 72 resurfacing project in operation that requires a portion of that budget. Both Fitzkee and Kim are quick to reiterate that this project, like nearly all others, is being put in place for the safety of the public.

The resources required for a project like a potential Cumberland reversion compound quickly. New signals, turn lanes, signage, parking, as well as the upkeep of these, all require portions of the budget, which is already used up quickly by projects elsewhere in the county.

The freight placed onto a single road like Cumberland would also necessitate significantly more work than one might assume. To properly accommodate the weight of the anticipated increase in traffic that would result from going two-way, parts (and potentially whole sections) of the underlying road structure would likely need to be redone from the foundation up.

If the road was not completely overhauled, the destructive forces of daily Route 422 traffic would make the road more susceptible to damage and an endless parade of repairs. This is because both directions could theoretically stay on Cumberland all the way through the city, instead of splitting off onto other roads (and consequently, spreading smaller amounts of wear-and-tear onto the road system).

But imagine that a two-way Cumberland project gets sufficiently funded and all of the road’s augmentations are in place. What happens then?

Congestion & Business

The high traffic that Cumberland Street (along with Walnut Street) sees is at the heart of the problem. Annual average daily traffic numbers, according to PennDOT, range widely from around 8,900 to 13,000. The splitting of directional traffic on 422 into Cumberland and Walnut creates a more manageable traffic pattern, but as Kim noted, “you can’t build your way out of congestion.”

Drawing from his experience as Zoning Administrator, Kim added: “You can’t change downtown Lebanon as it looks now.” The buildings, sidewalks, and storefronts are simply not built far enough apart to accommodate a two-way Cumberland, especially in the Lebanon of today. Some towns have converted one-way streets to two-way with success, but Lebanon’s particular circumstances and high traffic considerations seem to officials not well-suited for a similar change.

As Kim said, parking in Lebanon is already “at a premium”–eliminating parking along Cumberland would exacerbate Lebanon’s lack of available spots. A two-way proposal, then, would have one lane of traffic for each direction. Without turn lanes, a single car waiting to turn off could hold up a growing line of traffic.

“If I know that a town is always backed up with traffic, I’m going to avoid that as much as I can,” said Fitzkee, speaking personally. In that scenario, a decision made to help a business district could actually have the complete opposite effect. Commuters within the city would sit in frustration on Cumberland, and potential new customers from out-of-town would avoid the congestion by bypassing the city altogether.

Kim added that many people like to use sidewalks to traverse the business district. Eliminating or decreasing the wide sidewalks of Cumberland to accommodate turn lanes or similar space would discourage foot traffic and walk-in business.

Changes to the street buildings themselves would also raise serious concerns over the destruction of history and Lebanon’s sense of identity.

The frustration that business owners in the downtown feel isn’t lost on Fitzkee. “I wouldn’t disagree, if I were a business owner.”

Kim added on: “Two-way traffic might get a business an extra hundred customers a week.”

“But it might also lose them a hundred customers.”

Safety

The foremost concern of Kim and Fitzkee, as well as dedicated transportation planners the world over, is the safety of the public.

Traffic, from the commuter’s perspective, is more a nuisance than a danger to public health. But traffic’s side-effects are all the more reason to try and mitigate it, which include the delay of emergency medical services, increased air pollution into the local and public environment from idling cars, and stasis-induced road rage, a chronic symptom of millions put in traffic.

The possibility of freak accidents along major roadways, which might require massive rerouting or even evacuation of an area, plays a part in the decisions of planners. If such an accident happens (e.g. the derailment of oil tankers on a train), the question becomes how and where to redirect traffic.

Pedestrians, cyclists, and the like are also a major factor in safety considerations. Families, students, and any others headed through downtown could potentially be placed at a higher risk due to two-way 422 traffic, especially if a decrease in roadside space is made. Any lives that may be saved by Cumberland being one-way are worth the inconvenience.

“Safety always trumps convenience,” said Kim. “Safety always has and always will be the primary concern.”

The Future

Barring an completely unexpected major change to Lebanon, the Cumberland Street decision of decades past is likely to stay in place. Transportation planning takes future decades and developments into account, as the one-way decision of the 1950s did. There are several key questions that Fitzkee, Kim, and the Planning Department keep in mind on a day-to-day basis, including:

- What does a community, along with its government, want a roadway to function as?

- How do you make a targeted investment with the best impact and the least downsides?

- How do you temper the needs and wants of the now against the concerns of the future public?

These are the questions that Fitzkee and Kim continually ask themselves.

There is a delicate balance of safety, efficiency, environmental concerns, community, and business development that goes into these decisions. “There’s no right or wrong answer,” Fitzkee emphasized.

Kim: “If you commit to a project, though, you’d have to be prepared to live with the consequences.”