This column was submitted to LebTown. Read our submission policy here.

It’s been 100 years since Lebanon’s Nelson George Greene began his professional baseball career. In his day, Nelson’s exploits on the diamond were well-chronicled; he was somewhat of a celebrity about town, and interested readers could follow his rise up baseball’s ladder. Such was the measure of Nelson’s local renown, on the day he left town in February of 1924, the press reported that, “At the [train] station this morning he gave goodby[e] to one of the largest gatherings of friends that has assembled at Eighth and Scull streets for this purpose in years. The gathering not only consisted of athletes, admirers and personal friends, but included a number of the city business men, who are deeply interested in the twirler’s future.” It was a future the young man could hardly have imagined.

That future had been set in motion four years earlier and 400 miles away. In 1920, Doherty Park, in Durham, North Carolina, home of the Class D Piedmont League’s Durham Bulls, hosted baseball games for the first time since the 1917 season, which had been abbreviated by America’s entry into the war. While the Bulls weren’t very good in 1920 (they finished sixth in a six-team league), they had one very good player, a pitcher, known simply as “Lefty” Nelson. Naturally, Nelson was a southpaw — a lefthander. As the Bulls struggled to collect wins, more often than not they could count on Nelson to deliver them. On May 15, with the Bulls having won just seven of their first twenty games, the Durham Morning Herald reported of the previous afternoon’s game that “Lefty,” during a 3-1 victory over High Point, had provided the “best exhibition of southpaw twirling that has been given by local pitchers this season.” A month later, on June 24, the headline announced that the first-place Greensboro Patriots had been “humbled” by Lefty Nelson, as, in a 4-2 defeat, the “Southpaw Proved Too Much For the League Leaders.” The next month brought little relief to the Bulls’ opponents. On July 9, in Nelson’s “best game,” a 10-2 win over Danville, “he worked easily and had the visiting batsmen guessing.” That win was Lefty’s ninth in a row. Nelson maintained his winning ways for the rest of the season, on the way to a league-leading 23 wins.

Such an overpowering performance didn’t go unnoticed among baseball’s inner circle. “Mike Finn,” it was reported, a Detroit Tigers scout, had been watching the Bulls and had “expressed himself as being pleased with Nelson’s work.” There’s no record, however, that Lefty received any offers at that time.

Lefty was back with Durham in 1921. In April, though, fans were let in on a little secret. “Nelson Greene is the right name of the star southpaw of the Durham team of the Piedmont league,” the press divulged, “although last season he was known as ‘Lefty’ Nelson … Greene, a former Lehigh University pitcher, had a desire for a longer college career and camouflaged his name last season. This year he will be known by his proper name.”

Greene hadn’t set out to be a professional baseball player. A member of the Lebanon High School Class of 1918, Nelson had initially planned to pursue an engineering career. After a brief detour to Atlanta as part of the Army’s Officer Training program, Nelson had spent 1919 at Lehigh, supplementing mechanical engineering studies by joining the freshman baseball team. That he would pursue the sport as an amateur was practically a given. Indeed, Nelson loved baseball. At Lebanon High, he had played on the varsity, taking the mound during home games at the Bethlehem Steel field, on Third and Green Streets. It’s possible that the young man was there the day in September of 1918 that Babe Ruth played for the Lebanon team in the Steel League, although more likely, Nelson had already left for the Army. For nostalgia’s sake, it’s fun to envision the 18-year old watching enthusiastically among the crowd, but no matter. He and Ruth were destined to later cross paths.

Whether intended or not, Nelson’s freshman year at Lehigh was also his last. After spending the Christmas holiday in Lebanon (he lived with his grandmother, Hettie, at 40 Cumberland Street), the last glimpse we have of the young man at the school was in February of 1920. Then, it was reported, he had finished his mid-year exams at Lehigh and returned to Lebanon for a week or so to visit his relatives. By all accounts, he was never again enrolled at the school.

Somewhere along the way, Charles “Pop” Kelchner had entered Nelson’s life. After a long career as a professor and coach at Albright College, in 1918, Kelchner, a Myerstown resident, had become physical director at the Lebanon Steel plant, and in 1920, general secretary of the Lebanon YMCA, where Nelson frequently worked out. Additionally, Kelchner was also one of major league baseball’s foremost scouts. Kelchner recommended Nelson to Durham, and Lefty Nelson’s professional career began.

Of such decisions are lives often made. In his later years, Nelson was once asked by his son, whose own son showed potential as a baseball player, what to do to further that potential. “Break his legs,” Nelson disingenuously replied, “ so he can’t play sports. Then send him off to a good college so he can study hard and prepare for a great career.” The old man knew what he was talking about.

With the pursuit of his baseball career firmly underway, the afternoon of Oct. 9, 1922 in Lebanon, provided Nelson a fabulous opportunity to gauge his progress. Having just completed a dismal seventh-place season, an assemblage of Philadelphia Athletics’ players (with a few Phillies playing, too) began a barnstorming tour, and that day, arrived at the Steel League field to take on a team of Lebanon All-Stars. The 22-year old Nelson, fresh from a 15-11 season with the Class C Danville (Virginia) Tobacconists, was named Lebanon’s starting pitcher. It was an exciting day in town. R. Ray Miller, the team’s manager, proprietor of Lebanon’s Miller Grocery Store, had arranged the game, and had worked tirelessly to advertise the contest. He sat on the home bench, puffing away at an ever-present long black cigar. An estimated crowd of 5,000 was on-hand, with hundreds more watching from vantage points outside the stadium: atop box cars along Green Street’s Pennsylvania railroad lines; as well as “housetops, tree tops, telephone poles… and other points where they could get a glimpse of the field … Automobiles,” too, “were parked in solid lines all along Third street, from Green to Chestnut, and up and down Green, Willow and Spring streets. It was by far the biggest crowd of fans to witness a baseball game at Bethlehem Field since the days of the Steel League.” Pop Kelchner, Lebanon’s chief coach, roamed Lebanon’s coaching line, wearing the uniform of his employer, the St. Louis Cardinals.

Nelson had his work cut out for him. If not all of the Athletics starters had committed to play, one who had was Edmund “Bing” Miller, the Athletics’ starting centerfielder. Miller had been one of the few bright spots in an otherwise dismal season for the A’s; in only his second season, although at the advanced age of 27, Bing had hit 21 home runs, fourth best in the American League, and batted .335 (fifth best). Miller also garnered a number of votes as the American League’s Most Valuable Player. During batting practice, Miller deposited a few blasts over the left field fence, so Nelson would have to be careful with his offerings to the right-handed slugger.

In the end, the game wasn’t even close. Perhaps the major leaguers failed to give their all, but that day, Lebanon, with Nelson pitching the entire game, “played rings around the barnstormers,” and won, 8-2. Among nine hits Nelson allowed were two singles by Bing Miller, plus Miller’s potential triple that was run down for an out by Lebanon’s centerfielder, who made a “beautiful catch.” Additionally, Nelson registered three strikeouts. On the whole, noted the press, “Greene’s work on the mound was quite equal to that of [Lefty] Weinert of the Phillies, his opponent.” Nelson had proven his mettle against major league hitters. Soon, he got a chance to face the most powerful slugger of them all.

If, as has been said in sports, winning is the only thing, then 1923 was the year that Nelson finally got to experience the only thing that mattered. He also realized several pivotal personal achievements. It was his breakout year. As the pitching ace of the Class B Richmond (Virginia) Colts, who played their home games at Mayo Island Park, on the banks of the James River, Nelson posted a sensational 19-11 record. Despite his efforts, though, the Colts came out on the short end of a disputed pennant chase and lost the Virginia League championship to the Wilson (North Carolina) Bugs by .001 percentage points. Yet, through the historical prism of 97 years, the most exciting news was announced in a small June 4 headline in the Lebanon Daily News: “Nels [sic] Greene Pitched Game For Richmond,” it declared; “Against New York Yanks—,” before 15,000 fans, he “Struck Out Babe Ruth, Bob Meusel and Hinky Haines… Against Greene, Ruth hit no home runs.”

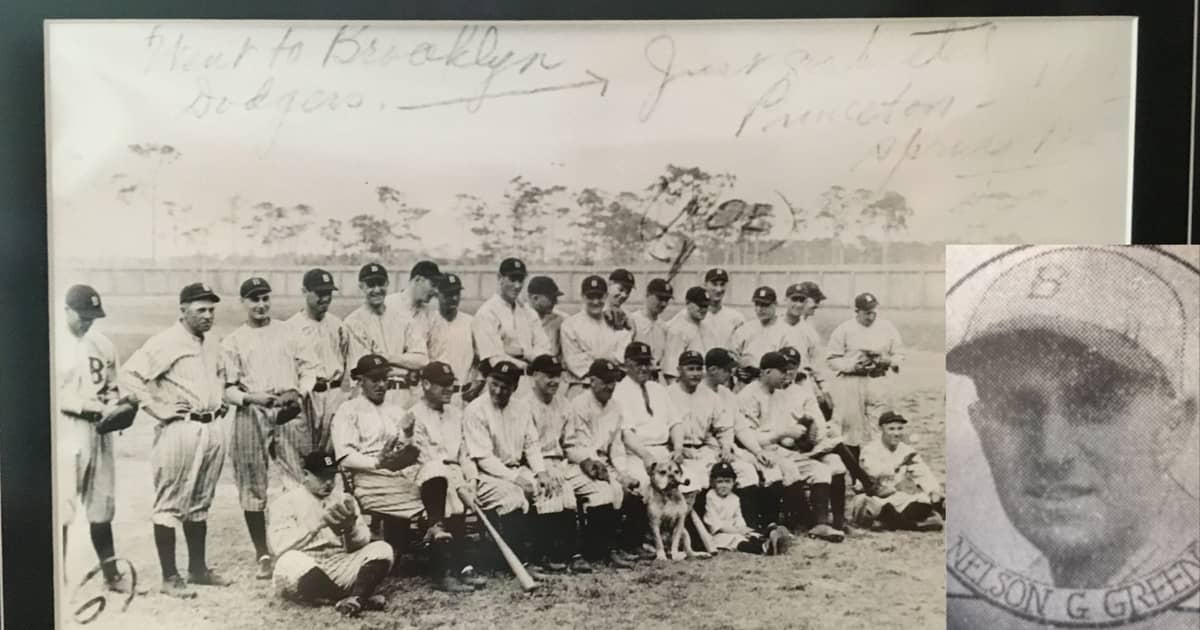

It was only an exhibition game, a regular occurrence back in those days, but Nelson had struck out the “Sultan of Swat” in a year in which Ruth would hit a league-leading 41 home runs. In addition to the Yankees, other big name clubs also played the Colts, among them the Giants, the Cardinals and the Dodgers. And it’s the latter team against whom Nelson made the biggest impression; for in September, he signed a major league contract to play for Brooklyn.

For all the euphoria the young man must have felt, Nelson’s major league career wasn’t bound to last long. On Oct. 4, he was in Brooklyn to pitch the final four innings of a seven-inning exhibition game at historic Washington Park, the precursor to the Dodgers then-current stadium, Ebbets Field. (The proceeds of the exhibition would be used to fund the conversion of Washington Park into a public recreation park.) At season’s end, Nelson then returned to Lebanon to prepare to try to make the team the following spring. (In Lebanon, the 6’, 1” Nelson played center for the St. Joe’s Catholic Club basketball team. The previous winter, he’d played the same role with Ray Miller’s champion city league club.)

So it was that in February of 1924, many of Lebanon’s townsfolk turned out to the train station to see Nelson off for Clearwater, Florida, where the Dodgers trained. Following a good camp, he made the team. On April 28, Nelson made his major league regular season debut, working three innings of relief at Boston, against the Braves. Then, Nelson made what would be, perhaps, the highlight of his all too brief major league career. It came on June 3, at New York’s Polo Grounds, against the New York Giants. Whether Brooklyn’s manager, Wilbert Robinson, made a calculated move or just didn’t have a rested starter, is unclear; but in the second game of a doubleheader, Nelson was called upon to start against the Giants. As the press reported the next day, the southpaw was “not so bad;” in three innings, he “showed nerve, control and a great curve.” In the third inning, though, he surrendered a monstrous home run to a future Hall of Famer, Giants’ shortstop Travis Jackson, and eventually lost, 3-2. Nelson pitched twice more that season, and was then sent to the minors. The following season, he again made the team, pitched eleven games in relief, and was again sent to the minors. Despite some interest over the years from other teams, Nelson never returned to the major leagues.

Like thousands of ballplayers before him, Nelson tried to hang on in the minor leagues for as long as he could. Finally, with Harrisburg, in 1931, his arm gave out. He was 31 years old; his prospects, quite limited. In December of 1924, undoubtedly flush with the visions of major league success, Nelson had married Elsie Brensinger, she from a well-respected family in the southern part of town. Their first child, Nelson, arrived in April of 1926; Robert, in July of 1930. Nelson’s family was complete.

Here, for most of the next decade, the 1930s Depression -era story of the down-on-his luck soul searching for a way to feed his family, resounds. As a general contactor, Nelson moved from job to job; in fact, the 1940 census recorded him as unemployed. Yet, so, too, does his story contain a happy ending.

Nelson, indeed, became an engineer: In April of 1942, he enlisted in the United States Army Corps of Engineers. For his first assignments, he returned to the area of his greatest baseball glory, Newport News, Virginia. Five years later, Nelson was sent overseas, to Berlin, and it was there that his true life’s calling was realized. Following the war, Germany had been split into Western (Allied) and Eastern (Russian) zones. Berlin itself was also split into Western and Eastern zones; ominously, though, the capital city was situated completely within the Russian zone. In June of 1948, Russia blockaded Berlin, closing all ground, canal and railway access into the Western side of the city, cutting off all life-sustaining supplies from the west. In response, the Allies began the Berlin Airlift: Over the next fifteen months, they flew round-the-clock flights over open air corridors from Western Europe to the beleaguered city.

Such an operation required constant maintenance not only of Allied airplanes, but also, especially, of Berlin’s airport runways. Three airports were utilized during the Airlift: Gatow, the British field; Tegel, the French; and Tempelhof, in the American zone. In May of 1948, Nelson had been named Construction Chief of the Berlin Military Post. In that role, his primary responsibility was upkeep of both Tegel and Tempelhof, as well as other construction projects critical to the success of the Airlift. For almost a year, Nelson led hundreds of men in performing 24-hour runway repairs to ensure successful takeoffs and landings of Allied aircraft. Every 30 seconds, a plane took off or landed from West Berlin, and the runways’ surfaces were in constant need of care. In March 1949, however, Nelson’s tour was completed, and he was due for return to the United States. With numerous vital projects underway, the timing couldn’t have been worse.

Rather than go home, Nelson resigned his commission and became a civilian engineer. By doing so, he was able to remain in Berlin and continue the work that he’d started. Although the Russians officially lifted the blockade in May, the Allies continued the Airlift until September of 1949, in order to stockpile supplies should the need ever again arise to feed West Berlin’s two million citizens. Shortly thereafter, “in recognition of his exceptionally meritorious service,” Nelson was awarded the Army Commendation Medal by General Lucius Clay, the United States Military Governor. The lefthander had become a hero after all.

In January of 1957, following several years stateside service in Baltimore, Lieutenant Colonel Nelson Greene retired from the Army and returned for good to Lebanon. For the rest of his life, until his death in 1983, Nelson and Elsie resided at 212 E. Grant Street. They lie today at Lebanon’s Mt. Lebanon Cemetery.

On Nov. 2, 1970, at Lebanon’s Treadway Inn, Nelson was inducted into the Central Chapter of the Pennsylvania Sports Hall of Fame.

Nelson “Chip” Greene, the grandson of Nelson George Greene, is a project manager/federal government contractor. A baseball historian, he has been a member of SABR, the Society for American Baseball Research, for over 15 years. Chip has written numerous baseball essays which have been published both on-line and in print. He lives with his wife and daughters, in Waynesboro, PA.