This article is shared with LebTown by content partner Spotlight PA.

By Marie Albiges of Spotlight PA

HARRISBURG — Liz Forrest doesn’t expect four of Pennsylvania’s most powerful lawmakers will pick her — a semi-retired technology consultant and failed state legislative candidate from Pike County — to be the potentially deciding vote in how they redraw their political districts this year.

Past chairs of the Capitol’s redistricting commission have included Ivy League law professors and retired judges. Beyond settling politically charged disputes, the chair is in a position to cast the tie-breaking vote on state House and Senate maps that determine which voters go where, which communities are split apart, and which lawmakers have a shot at getting re-elected.

“I doubt seriously they really are looking for ‘somebody like me,’” Forrest said. “I’m just going to put my name in, and it either works or it doesn’t.”

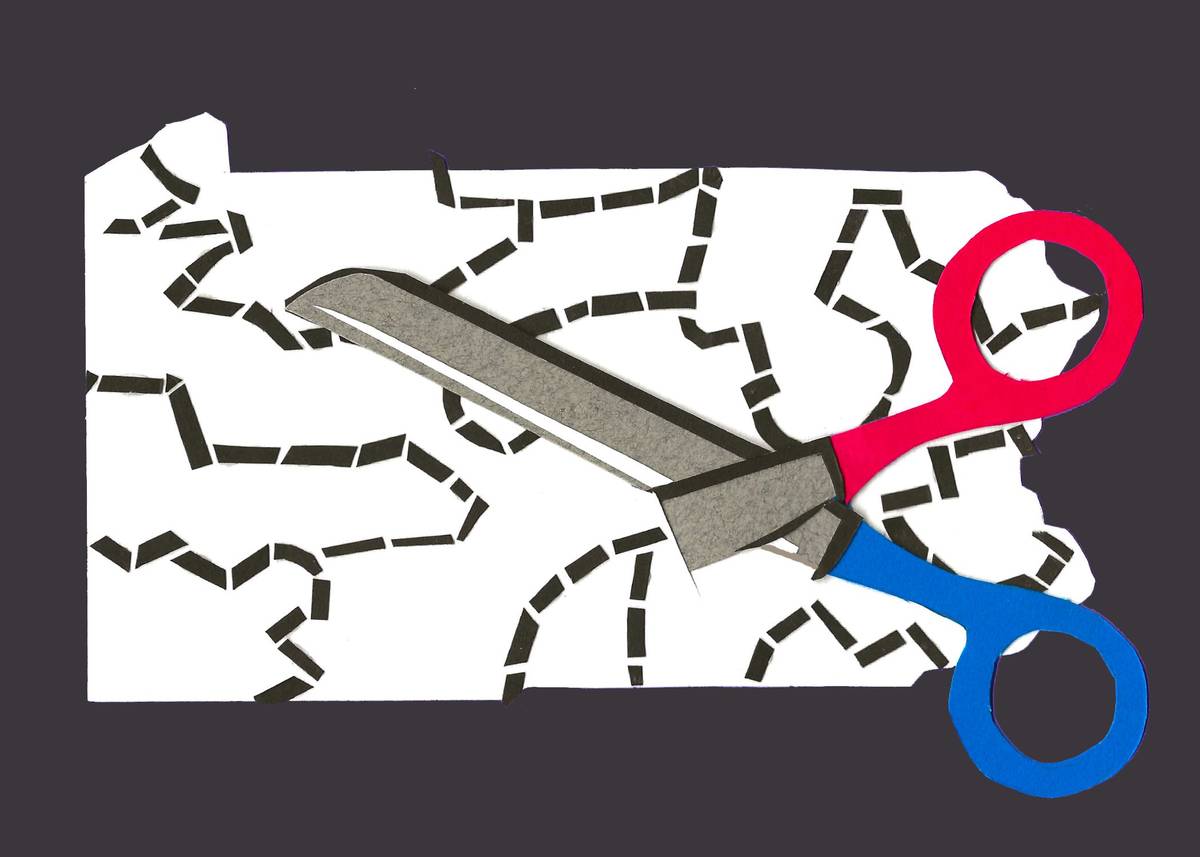

The once-a-decade process to draw new political maps — normally done in secret with little public input — is officially underway in Harrisburg, and the General Assembly’s Democratic and Republican caucus leaders are accepting applications from members of the public to chair the powerful Legislative Reapportionment Commission. It’s only the second time in the commission’s five-decade history that lawmakers have done so.

But it remains to be seen whether this year’s open application process would lead to selecting someone like Forrest, or a seasoned political insider once again.

While they’ve stressed the importance of having a fair and transparent redistricting process, most of the commission’s members told Spotlight PA and Votebeat it’s too soon to elaborate on what they’re looking for in a chairperson. They have less than a month to name someone or cede that responsibility to the majority-Democrat state Supreme Court.

That’s what has happened during nearly every redistricting cycle since 1971. Now, with Harrisburg at peak levels of partisanship, advocates pushing for more public involvement and transparency are hoping history doesn’t repeat itself and commissioners choose an independent chair.

Despite the pressure that comes with the job — specifically, the charge of casting the crucial swing vote on maps that can ultimately determine control of the legislature — almost anyone can qualify, even those who are eyeing a run for public office, are related to politicians, or work as lobbyists or for campaigns.

Past chairs have included Republican Stephen McEwen, a retired Superior Court judge from Delaware County; former U.S. District Judge Robert Cindrich; and James Freedman, a former dean of the University of Pennsylvania Law School.

“I think [lawmakers] understand that we’re in a new political era where Republicans and Democrats, right and left, there’s a real interest in transparency and openness,” said David Thornburgh, managing director of the anti-gerrymandering organization Draw the Lines. “I think the leadership is much more interested in recognizing that than pushing back.”

Draw the Lines and other advocacy groups focused on removing politics from the redistricting process, like Fair Districts PA and Common Cause PA, are encouraged by state Sen. David Argall’s bill that puts guardrails on who can serve as chair.

The measure, which passed unanimously out of a Senate committee in March, prohibits a person from holding the role if they or their spouse were registered lobbyists or political candidates in the past five years, or worked for a political campaign or public official in the past five years. The full Senate won’t return to Harrisburg until April 17, leaving little time for it to be considered in that chamber and the House before the commission’s April 30 deadline.

“I saw this bill as at least one small step in the right direction trying to make it a little less cutthroat partisan,” said Argall (R., Schuylkill), who’s served as a lawmaker through three previous redistricting cycles.

Argall said he’s had brief conversations with the four members of the Legislative Reapportionment Commission, but that it was “too soon to tell” if they would agree to pick a chair with his additional criteria in mind.

A spokesperson for Senate Majority Leader Kim Ward (R., Westmoreland), Erica Clayton Wright, said a reporter’s questions about commission members pledging to follow Argall’s criteria were “a bit leaning implying we have preconceived notions about a fifth member.

“The reality is a request for nomination was just issued [March 26],” Wright said. “We are looking forward to evaluating and reviewing the qualifications and credentials of the individual candidates based on merit.”

Through a spokesperson, House Majority Leader Kerry Benninghoff (R., Centre) said he was looking for someone who could be “a neutral arbiter who shares our commitment to a fair, open, and legal redistricting process.” He said the public application process would ensure — “assuming we can agree to a candidate” — that the person is “best qualified and not the outgrowth of political favoritism or nepotism.”

Senate Minority Leader Jay Costa (D., Allegheny), the only current commissioner who also served on the 2011 commission, said the panel should adopt Argall’s criteria and that he’s personally committed to applying the criteria to his search.

Costa is also looking for someone who is “going to be committed to working for the right outcome, in terms of a fair outcome, an equitable outcome.”

Scholars and redistricting experts have found that the party in control of redistricting often has a partisan advantage in the resulting maps.

But determining whether a map has been purposefully drawn for that reason — referred to as gerrymandering — is much more complicated. For one, Democrats tend to cluster in urban environments, while Republicans are spread out across the state, resulting in some naturally uneven districts.

Argall hopes his bill will reduce distrust in state government, which he said reached an “all-time low” in the past year thanks to misinformation surrounding the 2020 election and the government’s role in dealing with the coronavirus pandemic.

“I feel sometimes as if I’m working in a room full of gasoline fumes and people are flicking their lighters,” he said.

The Republican-controlled General Assembly has in the past failed to advance efforts to create an independent redistricting commission without lawmakers, or at least rein in their power. Courts and scholars have found that when left up to their own devices, lawmakers in charge of the redistricting process will gerrymander maps, or draw them in ways that help them win as many votes as possible while minimizing the voting power of their adversary.

Pennsylvania’s 2011 congressional map — drawn largely in secret by the GOP lawmakers and approved by a Republican governor — was considered one of the most gerrymandered of the time, and in 2018, the state Supreme Court threw it out, saying Republicans gave themselves an unfair advantage.

Argall will play a powerful role in that process this year as chair of the Senate State Government Committee, which considers the map, and he said he’s planning a round of public hearings.

While the congressional map-drawing will still be led by Republicans, they’ll have to work with Democratic Gov. Tom Wolf — who must give his stamp of approval — if they want to avoid the map being challenged in court.

“Will that lead to bipartisanship?” Argall said. “I hope so.”

WHILE YOU’RE HERE… If you learned something from this story, pay it forward and become a member of Spotlight PA so someone else can in the future at spotlightpa.org/donate. Spotlight PA is funded by foundations and readers like you who are committed to accountability journalism that gets results.