American food has always been distinguished by its simplicity. It’s bacon and eggs, coffee, hash browns, pancakes and waffles, cheeseburgers and fries, milkshakes, and homemade pies. In short, it’s anything that one might expect to find on the menu at the nearest diner.

Over the last century, the diner has emerged as one of the most convenient and popular places to eat in the United States, contending even with the rise of fast food and takeout. But far from providing good food and a comfortable atmosphere, the diner has also been among the most quintessential manifestations of American ideology.

Starting in the mid-20th century, it has been readily embraced by American culture, not just as part of a society that loves food but as a symbol of post-World War II optimism, 1950s industriousness and prosperity, and the egalitarian promise of the American dream.

Accordingly, the diner has become a compulsory stop on the campaign trail for U.S. presidential candidates, regardless of their political affiliation. Most famously, the walls of New Hampshire’s Red Arrow Diner are adorned with pictures of visiting political candidates as diverse as Al Gore, Hillary Clinton, Barack Obama, and Donald Trump (although none are quite as prominent as the much larger portrait of Guy Fieri right next to them).

Additionally, the diner boasts a significant presence in American art. It has been used as a conduit to explore the American experience in interpretations ranging from Edward Hopper’s “Nighthawks” to Norman Rockwell’s “The Runaway.” Perhaps more ubiquitously, it also appears regularly in American cinema, providing the setting for memorable scenes in “Grease,” “Seinfeld,” “Pulp Fiction,” and “Moonlight,” among many other well-known movies and sitcoms.

The history of the American diner

Many consider the first diner in America to be Walter Scott’s in 1872, though his establishment more closely resembled a food truck. Scott began by selling food out of a horse-pulled wagon to late shift workers at the Providence Journal in Rhode Island. At first, these were called “night lunch wagons,” but after several decades and numerous modifications, they came to be known as diners.

Originally, the first diners, like Scott’s, operated later in the evening when other restaurants had closed and served food mainly to late shift workers; as owners shifted from using wagons to prefabricated buildings, they continued to stay open late at night and cater predominantly to the working class. This meant that these prefabricated diners were often assembled in densely populated or industrialized areas, usually right off highways.

During this time, three of the most prominent companies producing prefabricated diners were Tierney and O’Mahoney, which were based in New Jersey, and Worcester, which was based in the Massachusetts city of the same name. This geographically limited the expansion of diners to the northeastern United States up until the mid-1920s.

Train cars provided the inspiration for their design, and with functionality in mind, diners began to resemble the arrangement of a dining car. When trains began to adopt a sleek chrome exterior during the 1930s, diners did as well. For most people, the mention of a diner still brings to mind that nostalgic and essential combination of retro chrome and stainless steel.

By the 1940s, diners had spread just about everywhere in the country. They would reach their peak popularity in the 1950s, and this would catapult them to their present iconic and quintessentially American status.

Diners arrive in the Lebanon Valley

Because Pennsylvania was nearby to most of the biggest names in diner manufacturers, diners began to appear in Lebanon County as early as 1935. One of the first to emerge in the area was the Lebanon Diner, which opened on Nov. 8 of that year. It was built by Jerry O’Mahoney Diner Co., and it was the first of many diners and restaurants to be owned and operated by the Pushnik brothers.

The Pushniks were a large family. There were John and Mary, their ten sons, John Jr., Louis, Frank, Anthony, Andrew, Edward, William, Joseph, Richard, James, and two daughters, Ann and Esther. Most of the boys would serve in the army during World War II, and they were stationed, collectively, throughout Europe, Africa, and Asia.

Read More: How Italian restaurants got their start in Lebanon County

Prior to the war, however, some of the brothers had already begun to enter the restaurant business in Lebanon County. During their first several years of operation, they encountered significant challenges, but despite early altercations with law enforcement, the Pushniks would eventually become one of the most well-known and respected families in Lebanon County.

By 1937, Louis was running the Lebanon Diner at 12th and Cumberland; on Aug. 19 of that year, local police conducted raids of establishments in the city of Lebanon, and he was arrested for possession of a slot machine in his establishment. On Sept. 18, he was fined $25 (about $460 today) after pleading guilty to maintaining an illegal gambling device.

Nearly two years later, on Oct. 12, 1939, when Edward and Andrew had taken over at the Lebanon Diner, local police officers conducted similar raids throughout the city and found two punchboards at the brother’s diner. They were subsequently confiscated, and both Edward and Andrew were charged with maintaining illegal gambling devices.

These two incidents would be far from the Pushniks’ last entanglement with law enforcement, but something much more momentous was about to disrupt their lives in the states and suspend their ambitions of becoming successful restaurateurs.

When charges were leveled against the Lebanon Diner for the second time, World War II was already well underway. The Nazis invaded Poland on Sept. 1, and by December, British forces were engaging the Nazis directly in aerial and naval combat, notably during the battle of the Heligoland Bight, which took place Dec. 18. Over the course of the next several years, many of the Pushniks would find themselves overseas playing an integral part in the war.

Their contributions did not go unrecognized and Edward in particular was an exemplary and well-decorated soldier, enlisting in 1942 and serving as a staff sergeant in the 80th Infantry Division of the army up until 1945. On one occasion related in the Lebanon Daily News, he abandoned cover while under heavy artillery fire to rescue two fellow soldiers who were drowning during an attempt to cross the Sauer in Luxembourg.

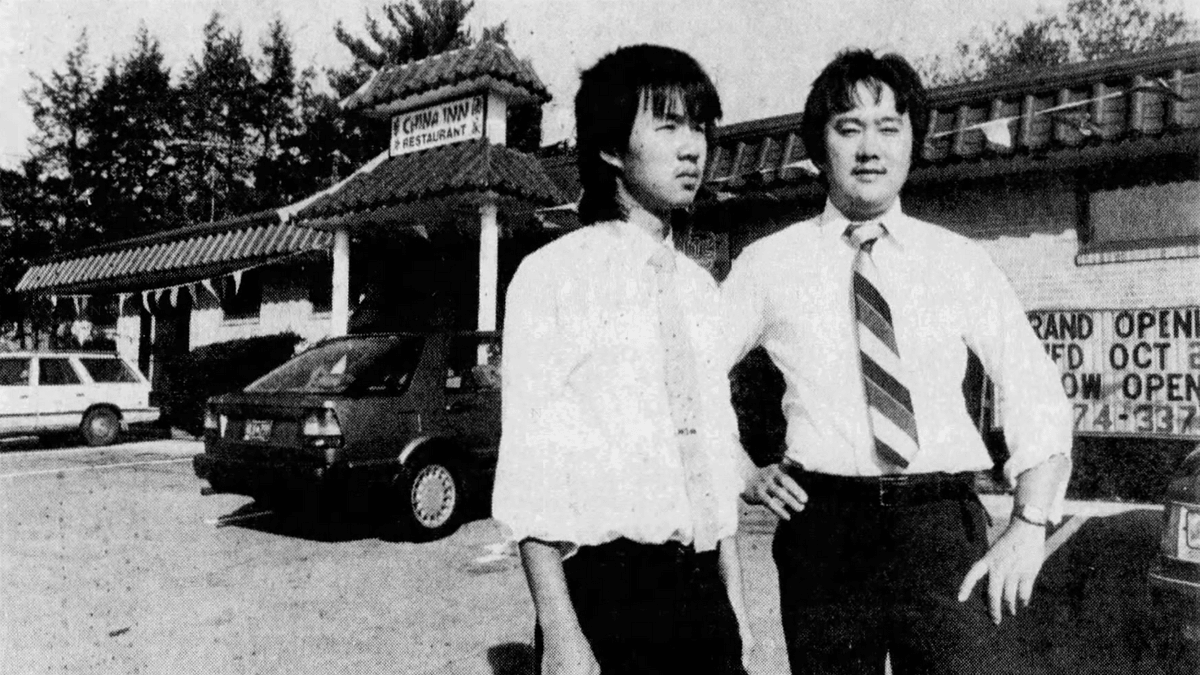

Read More: How Chinese cuisine made its way into Lebanon County

Edward’s repeated heroics throughout the war ultimately earned him a Purple Heart, two Bronze Stars, and two oak clusters.

His brother Andrew also enlisted in 1942. He received training for one year at Indiantown Gap as a member of the 111th Infantry, during which time he remained the proprietor of the Lebanon Diner. Among their other brothers to serve in the army were William, Joseph, Richard, and James.

The Pushnik brothers go into business

Upon returning to Central Pennsylvania, the brothers quickly resumed control of several local diners. On April 5, 1946, Edward and Andrew bought the Star Diner for $5,000, and by 1948, the name had officially changed to Pushnik’s Lebanon Diner. From the start, they were open for 24 hours.

Several months later, on Nov. 23, 1946, Joseph and Richard went into business together and opened Pushnik’s Sandwich Bar at 1210 Cumberland St. — the place where several of their family members (including Edward and Andrew) had been living up until the war. Like the Lebanon Diner, the Sandwich Bar stayed open late; on Friday and Saturday, it wasn’t closed before 3 a.m.

In 1947, Andrew was going ahead with plans to open a bar, though he undertook this business venture without his brother Edward. It was to be called Pushnik’s Restaurant and East End Bar and would open on Weidman Street. Andrew’s wife, Gladys, was involved in this process, and when they divorced in 1948, the plans proceeded without Andrew, and “Pushnik” was dropped from the restaurant.

By 1948, the brothers opened a new restaurant at the location of the former Thomas’ Restaurant at 603 Cumberland St. Confusingly, they would advertise their new establishment under different names for the next several years, among them Pushnik’s Restaurant and Grill, Pushnik’s Restaurant and Cocktail Lounge, and Pushnik’s Bar and Grill. Richard would own and manage the establishment over the course of the next several years.

Also in 1948, William would purchase the already-established Fourth Avenue Café, a property on East Cumberland and 4th Avenue. It would later be renamed the Gin Mill in 1952 and would remain open for the next several decades, although it would change locations several times.

Like many diners and small restaurants, staff turnover was high, and workers came and went regularly. The waitstaff was often composed of students or recent graduates of local high schools, and the Pushniks constantly advertised in the Lebanon Daily News for positions that always seemed to be open.

On May 24, 1954, the brothers took over the management of the College Hill Diner in Fredericksburg and subsequently shortened the name to College Diner. It would remain open for the next several decades with ownership passing around the family, from Edward and eventually to his nephew Donald.

Around 1957, they opened Pushnik’s Cocktail Lounge at 1352 Cumberland St., an establishment which they expanded with the wildly popular addition of the Waterfall Room several years later. On its arrival in late Oct. 1964, it caused quite the commotion, and more than 250 people attended the grand opening, though according to Edward, it had the capacity for 400.

True to its name, there was a running waterfall inside the establishment along with lava stone to fit the South Pacific theme. In addition to the restaurant, there was also a dance floor and a stage for regular entertainment; the dining area was raised over the dance floor, allowing patrons to watch performers.

Richard Pushnik had been instrumental in securing some of the most noteworthy big band acts — among them the bands and performers of Harry James, Duke Ellington, Count Basie, Glenn Miller Orchestra, Tommy Dorsey, and Frank Sinatra Jr. — and bringing them in for performances in the Lebanon area, according to his 2004 obituary. Many of these artists were major figures in American jazz.

By Oct. 1963, the brothers had themselves incorporated as Pushnik’s Inc. James, who also worked as a chef at Pushnik’s Diner at 1350 Cumberland St., was the vice president up until his death in 1994. His brother Edward was the president.

There are a few reasons the brothers might have sought to have their business incorporated, not only for the tax breaks of operating as a single entity but also because it provided them additional financial security. During their years of operation in the Lebanon area, the Pushniks’ establishments were subject to frequent burglaries.

Some of these instances were more amusing than serious, as when two young boys stole a beer keg from Pushnik’s Diner and were apprehended trying to roll it out of a creek bed and up a steep 100-foot incline, but others were quite disconcerting.

These began as far back as 1943 when the Pushniks were still operating the original Lebanon Diner. In November of that year, a window was smashed during a robbery, and money was taken from the cash drawers.

Later in 1954, Pushnik’s Diner was part of an elaborate heist in which ten Lebanon diners were robbed in quick succession. It was also robbed at least once more in 1958. The College Diner, in particular, was the target of numerous robberies, at least one in 1956 and two in 1959, but likely several more.

The Pushniks themselves also faced various charges over the years. Typically, these involved possession of illegal gambling devices, as in a 1965 case involving Donald and the College Diner along with 46 other Lebanon County diners. Donald was eventually charged in 1966 despite an attempt to dismiss the cases on a legal technicality.

Probably the most serious charge occurred in 1962, however, when Edward and Andrew, along with one of their employees, Clyde Kleinfelter, were charged with unlawful possession and sale of drugs. The drugs in question were amphetamines or “bennies,” stimulants that can be prescribed legitimately for chronic fatigue and narcolepsy, but which nevertheless are considered potentially addictive and dangerous substances.

Kleinfelter immediately plead guilty. Edward and Andrew both plead not guilty, though at first, Andrew refused to enter a plea. The charge against Edward was ultimately dismissed in November of that year; however, Andrew was fined $500 and let out on probation.

Despite the occasional legal trouble, though, the Pushniks left a positive impact on Lebanon County, and indeed, across the state of Pennsylvania. Social groups like the Lebanon Rotary Club and the Industrial Management Club frequently met in their establishments, and the brothers’ active involvement in the community clearly attests to a family striving to make a positive difference in other people’s lives.

A legacy beyond the diner

Throughout their careers as successful restaurateur, the family remained active in the church. They were Roman Catholic, and the brothers belonged to several different congregations throughout Central Pennsylvania. In contrast to many other restaurant owners in the area, they frequently closed their establishments over the holidays to allow their employees to spend time with their families.

Joseph, who had served in Europe and Africa during World War II, was also active in veteran groups, notably the William Bollman American Legion post in Lebanon and the Disabled American Veterans chapter in Harrisburg.

Most of all, Edward was deeply concerned with contributing to society, and in his later years, he became well-known as a philanthropist. Coordinating with three other local diners in 1954, he has been credited with starting the local “Buck-a-Cup” program, which as of 1999, raised more than $8 million for children with disabilities in the Lebanon area.

He was also directly involved in supporting local education. In 1994, he donated $250,000 to HACC, which supplied books and created a scholarship fund for business students. As of 2021, it is still offered at the college as the Edward J. Pushnik Business Scholarship. This act of generosity led Frank Dixon, who was chairman of the HACC Foundation at the time, to name the library after Edward.

Read More: Giving is the best business decision Frank Dixon ever made

In 1995, he donated $10,000 to each of the following organizations: Quest, the Lebanon Chapter of the American Red Cross, the Salvation Army, the Good Samaritan Hospital, Lebanon County Career and Technology Center, Lebanon Catholic Hill School, St. Mary’s Catholic Church (he was also a member), and the Easter Seal Society of Lebanon County. At one point, the snack bar at the Good Samaritan Hospital was also named after Edward.

The Pushnik brothers ultimately became some of the most successful and magnanimous restaurateurs in the area, though during the past several years, their accomplishments have gone somewhat unremembered. Together, they epitomize the reasons the diner has become such an evocative American symbol, and their unwavering industriousness and commitment to the community serve as a powerful reminder of the individual people who helped to make the United States the country that it is today.

Questions about this story? Suggestions for a future LebTown article? Reach our newsroom using this contact form and we’ll do our best to get back to you.

Build the future of local news.

Cancel anytime.

Monthly Subscription

🌟 Annual Subscription

- Still no paywall!

- Fewer ads

- Exclusive events and emails

- All monthly benefits

- Most popular option

- Make a bigger impact

Already a member? Log in here to hide these messages

Local news is disappearing across America, but not in Lebanon County. Help keep it that way by supporting LebTown’s independent reporting. Your monthly or annual membership directly funds the coverage you value, or make a one-time contribution to power our newsroom. Cancel anytime.