Crack open a textbook about Pennsylvania history and you’ll likely learn that our commonwealth was a forerunner in scores of vital American industries, including iron, railroads, coal, oil, steel, automobiles, digital computing, snack food, and consumer goods — the list goes on and on.

Conspicuously absent from those tales of industrial trailblazing are mentions of whiskey.

Although today Kentucky might jump to mind when it comes to American whiskey, that paramount status had once been Pennsylvania’s to lose. Prohibitive liquor laws and an apparent disinterest in promoting whiskey suggest that Pennsylvania may actually have wanted to lose it, despite the fact that the liquor has almost absurdly American roots, with none other than George Washington making a cameo in our story.

Perhaps we’ve distilled the narrative a bit, but generally speaking this is the line of argument you’ll hear from Laura Fields, the multidisciplinary force behind two burgeoning projects that aim to raise awareness and foment a sense of pride and identity around the historical prominence of whiskey in Pennsylvania.

Few distillers played as significant a role in this Keystone State historical drama as Schaefferstown’s own Michter’s/Bomberger’s Distillery. The Schaefferstown distillery is today historically important not for the apocryphal tales of supplying General George Washington — almost certainly not true in a literal sense, although possibly valid in a sense that the distillery may have generally supplied the Continental Army.

Rather, for Fields, the historical interest lies in the hundreds of Pennsylvania distilleries that thrived here before Prohibition.

Fields explained through email and phone interviews with LebTown that Michter’s/Bomberger’s Distillery was one of the most important distilleries to survive that “noble experiment,” and it was the last of the great Pennsylvania distilleries to shutter operations, making it to 1990.

Dick Stoll was the last master distiller at Michter’s, on the watch when the distillery was abruptly shut down in 1990. Stoll died in 2020 but prior to that he was able to work with Fields at his eponymous distillery, Stoll & Wolfe, to produce a special blend based on what was a main ingredient to Michter’s marketing and the whiskey flavor itself – Rosen rye.

“When you think masterful distilleries you think Rosen rye, Michigan rye,” said Fields.

Brought to America from Russia by an academic who immigrated and ended up at today’s Michigan State, the grain became known for its use as a raw material for whiskey, occupying a premium status like Kobe beef or Maine lobster. Rosen ended up being grown locally, reaching commodity status and apparently still in demand (possibly more in demand!) during Prohibition, judging from a survey of Lebanon Daily News classified pages from the period.

For the last six years, Fields has been on a mission to return Rosen rye to Pennsylvania farmers and, in turn, to its distillers. Fields turned a 5-ounce sample from the USDA seed bank in 2015 to hundreds of pounds of the grain annually by present day – enough grain so that Stoll & Wolfe Distillery will even make Rosen rye whiskey one of its core products going forward.

Just 100 bottles were made in the initial release, and as you might expect, demand in the lottery for them was extremely high. This particular batch was the only one distilled by Stoll himself, but his business/distilling partner Erik Wolfe will be picking up the torch and plans are in place to ramp up production headed into next year.

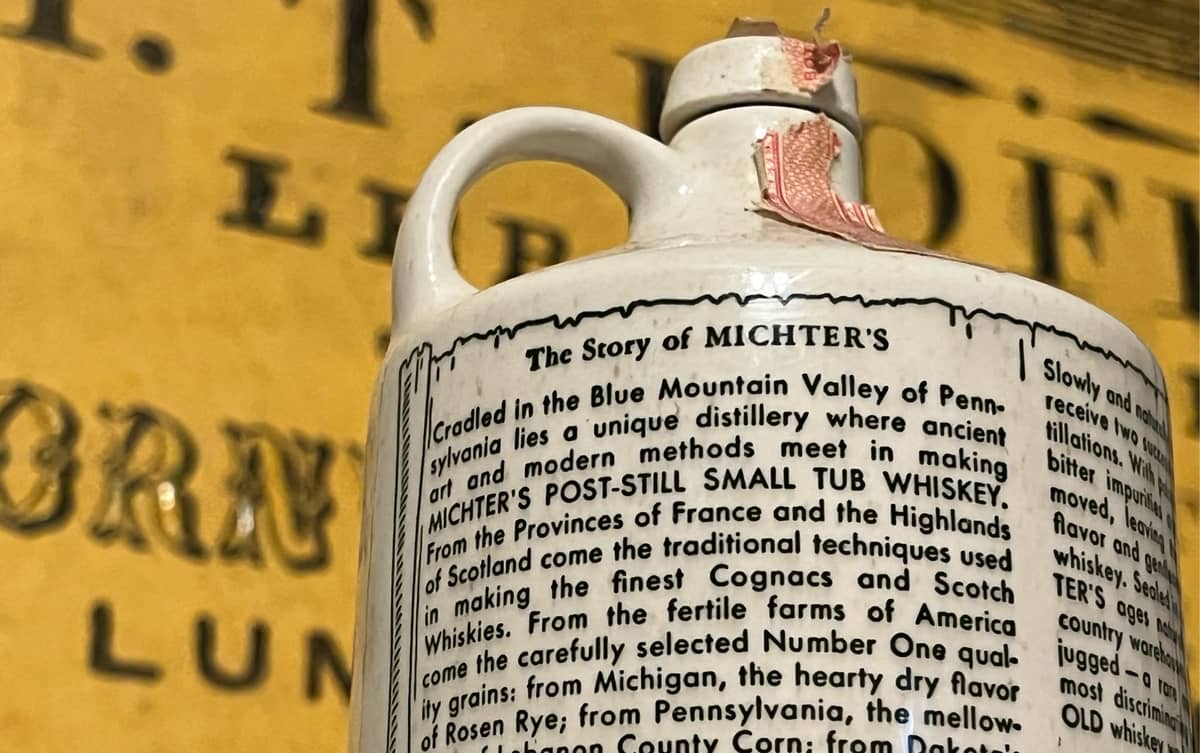

All this work was done by Fields through SeedSpark, the project she runs in conjunction with the Delaware Valley Fields Foundation to do this one thing. Fields said that the project was largely inspired by Michter’s specific use of Rosen in their whiskey mashbills, and noted that they even promoted its use on their product labels and printed advertising.

“My ongoing research into Rosen led me to understand that it was much more widely used,” said Fields.

“It was a tragedy to lose that grain to history, and it’s a real honor to be bringing it back for use in distilling again.”

Fields said that Michter’s likely sourced the Rosen rye grain through bulk contracts with local farmers. This is one of the scores of facts Fields currently has locked up in her brain as she undergoes her second major whiskey-related project — a forthcoming book that will showcase the individual distillery stories that, in aggregate, demonstrating that things were very different back then indeed.

Fields has identified approximately 200 historical Pennsylvania distilleries that she hopes to capture in individual profiles for the book. She expects the research will take a couple years, with Michter’s likely to have one of the largest entries. Fields shared an exclusive preview with LebTown, which we have excerpted below.

Excerpt from Fields’ entry on Michter’s

“One cannot talk about the history of Pennsylvania’s distilleries without mentioning Bomberger’s Distillery. It was, in fact, the oldest operating distillery in the United States until Valentine’s Day, 1990, when its doors were locked for the last time. It joined the rest of America’s distilleries when it halted operations during Prohibition but was one of the few distilleries to return to large scale whiskey production after Repeal. Modern whiskey historians have plenty to say about Michter’s Distillery, which was the name given to Bomberger’s in the late 1970s, but the name Michter’s does not encapsulate the legacy of one of the pillars of Pennsylvania’s distilling history. The longer legacy belongs to the descendants of John and Michael Shenk who been distilling rye whiskey there since 1753. The tradition and history of Bomberger’s Distillery is older than our nation. Its stills were lit the same year that a 21- year-old George Washington was receiving his first military appointment before the escalation of the French and Indian War. Pennsylvania would not even become a state for another 34 years!”

The Bomberger’s/Michter’s/Shenk’s site was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1980. (Read the nomination here [PDF].) It is not open to the public and also does not have structures other than the jughouse standing today.

Fields said that helping readers imagine the particular hugeness of enterprises like Michter’s at their peak will instill a generalized idea of just how impressive and unique Pennsylvania’s whiskey industry was.

To learn more about Fields’ work, check out the SeedSpark website or her personal blog, Dram Devotees.

Questions about this story? Suggestions for a future LebTown article? Reach our newsroom using this contact form and we’ll do our best to get back to you.

Build the future of local news.

Cancel anytime.

Monthly Subscription

🌟 Annual Subscription

- Still no paywall!

- Fewer ads

- Exclusive events and emails

- All monthly benefits

- Most popular option

- Make a bigger impact

Already a member? Log in here to hide these messages

While other local news outlets are shrinking, LebTown is growing. Help us continue expanding our coverage of Lebanon County with a monthly or annual membership, or support our work with a one-time contribution. Every dollar goes directly toward local reporting. Cancel anytime.