This article is shared with LebTown by content partner Spotlight PA.

By Angela Couloumbis of Spotlight PA, Joseph N. DiStefano of The Philadelphia Inquirer and Craig R. McCoy of The Philadelphia Inquirer

HARRISBURG — Following months of controversy and amid an ongoing federal investigation, Pennsylvania’s biggest pension fund on Thursday announced that its top two executives were leaving their jobs.

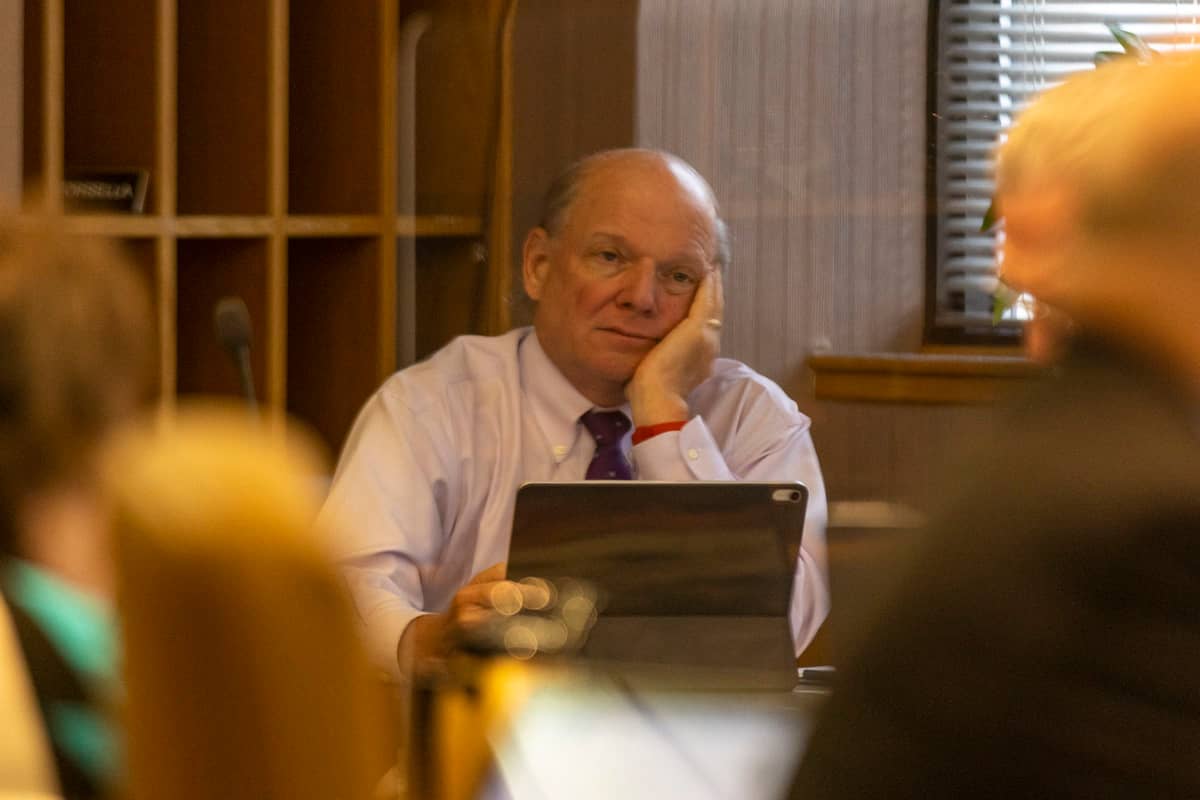

With no explanation and after a meeting closed to the public and media, the PSERS board said that executive director Glen Grell, 64, and investment chief James H. Grossman Jr., 54, were both retiring.

The agency said Grell would step down at the end of the year and be given a consulting role with the $73 billion fund. The board said little about that or about Grossman’s future during its meeting Thursday morning. Grossman, paid $485,000 yearly, has been the highest-paid employee in state government, paid for more than twice the governor.

Their departures from PSERS come as a scandal that has simmered around the agency for eight months has gathered significant momentum.

Two weeks ago, an outside law firm hired to scrutinize the fund said it had all but completed its probe and that the results would be damaging to some on the fund staff. The firm did not name anyone that would face criticism.

The pair’s tenure was marred by the fund’s admission in March that it had mistakenly adopted a false and inflated figure for investment performance, a declaration that immediately triggered a continuing federal criminal probe as well as a companion inquiry by U.S. financial regulators.

The 15-member volunteer board adopted a new, lower figure for fund profits in April, an embarrassing reversal that, in turn, forced it to hike payments into the pension plan by more than 100,000 working teachers and other school staff. This was driven by a state law that said teachers should share the pain when the plan’s performance falls short.

The debacle of the botched calculation was accompanied by a growing schism on the board in which dissidents, including Pennsylvania’s current and former treasurers, castigated the investment strategy pursued by Grell and Grossman. The critics said the strategy was too expensive, too illiquid, too opaque — and too unprofitable.

They complained that PSERS had far too much money invested in high-fee hedge funds and venture-capital projects, and other “alternative” financial instruments not sold on the stock market.

The fund rebounded last fiscal year along with the world economy, posting a record return of 25%, a massive jump from the previous year’s nearly flat return of 1.1%.

Still, the plan performance trailed more than a dozen other public funds and was well beneath the S&P 500 stock index’s climb of 38%.

In June, the dissident bloc on the board tried and failed in an initial effort to oust Grell and Grossman, mustering six votes to fire them, two short of a majority. In a sign of the pair’s waning influence, though, the full board consistently rejected the executives’ investment strategies in subsequent votes.

Grell, a lawyer, was named executive director of the pension plan in 2015. Before that, he served for 10 years as a Republican in the state House, representing a district in Cumberland County, south of Harrisburg. His annual pay at PSERS was $227,000.

Grossman, who has an accounting degree from Elizabethtown College, has worked for the pension plan for nearly a quarter-century and became the investment chief in 2013. He oversaw a highly paid team of 50 investment advisors, including two deputies each paid $399,000 yearly.

Board critics also challenged and eventually reined in spending on luxurious travel by Grossman’s staff, which flew the globe to check on fund investments. In an article in April, The Inquirer highlighted a series of ultra-expensive airfares and hotel stays by the staff. The trips were booked by vendors who did business with the fund.

PSERS — Public School Employees’ Retirement System — is among the top 25 public pension funds in the nation. Every year, it sends out $6 billion in retirement checks to 250,000 former school employees. In the last fiscal year, it was supported by $5 billion payments from taxpayers, $1.1 billion from school workers, and $12 billion in investment profits.

Despite that infusion of money, the plan has a $40 billion deficit. Retirees have not seen a benefit increase in nine years.

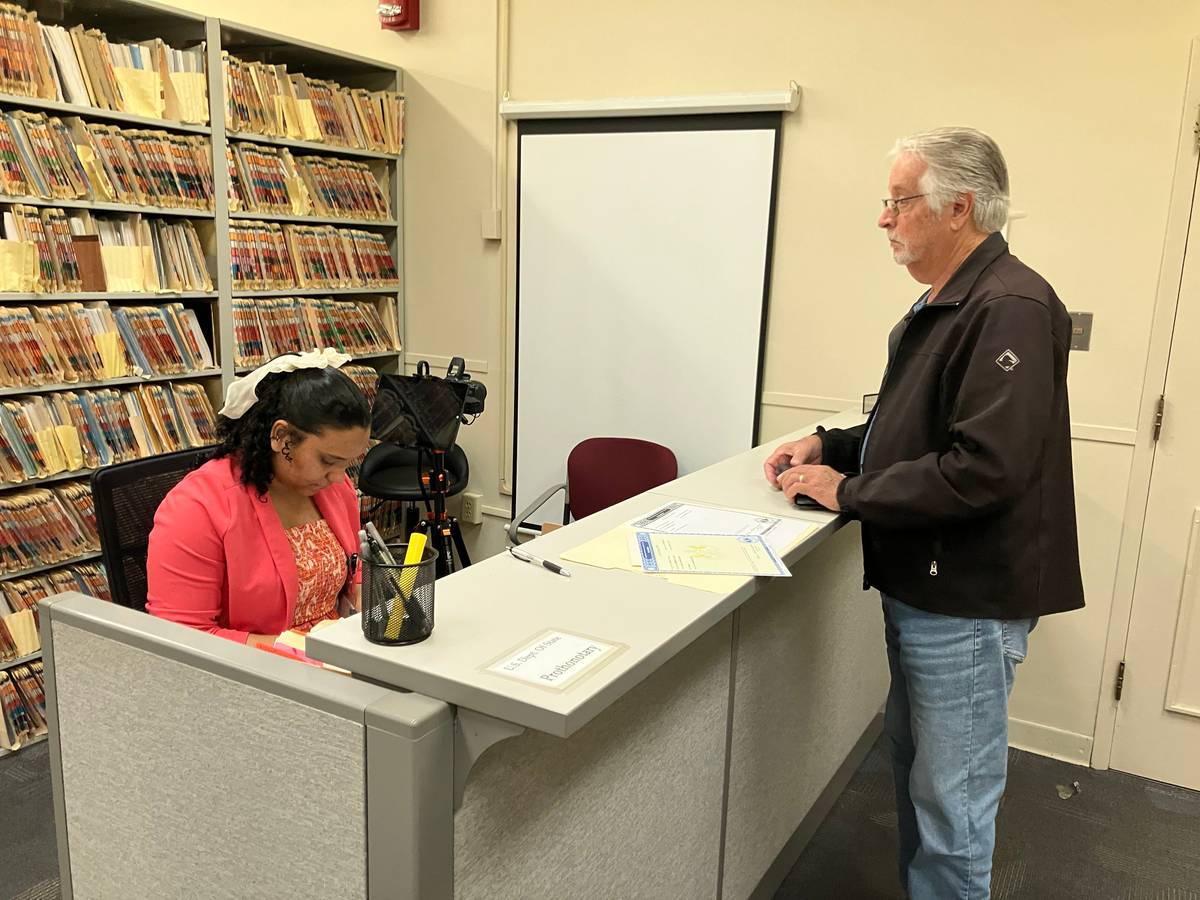

In response to a wave of federal subpoenas, PSERS has spent heavily to hire outside lawyers and financial advisers, with fees exceeding $2.4 million and climbing. The board hired two law firms to represent itself and the agency in dealings with the federal prosecutors — the FBI and the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission — as well as other firms to personally represent Grossman and seven other fund staffers.

The SEC, which joined the probe in September, has told the fund that it is looking into whether any staffers accepted gifts from vendors that did business with the system.

The agency hired Womble Bond Dickinson, a big law firm with offices in the U.S. and the United Kingdom, to conduct a parallel investigation into the matters under FBI and SEC scrutiny.

As the controversy moved toward its climax, the board has been hung up on just how much to reveal to the public. After maintaining silence about the math error for months and rebuffing requests from The Inquirer for information under the state’s Right-to-Know Law, the board has most recently had to deal with complaints from staff that any report would hurt their reputations.

Democratic Gov. Tom Wolf, who has three appointees on the board, came down on the side of disclosure.

“Making investigation results public would increase transparency and reassure the retirees and current members,” Wolf said in a statement Wednesday.

Ever since news of the federal investigations broke, PSERS has said virtually nothing about them. Its board has held virtually all discussions over the scandal behind closed doors and has fought requests for documents from The Inquirer filed under the state Right-to-Know Law — and even a lawsuit from a board member saying she was unfairly shut out of information.

The subpoenas, copies of which were obtained by The Inquirer and Spotlight PA, demanded testimony and documents both about the recanted calculation and, in a seemingly unrelated issue, about the fund’s purchase for several million dollars of a series of industrial buildings and parking lots nears its headquarters in the state Capitol.

In June, the fund admitted that Grossman and other members of his investment team had been listed on financial documents as being paid by both the pension plan and the firm managing the Harrisburg real estate. The plan said that was another error and the forms would be amended.

As for the botched calculation, the board adopted an inflated figure in December last year that was just narrowly higher than the figure it needed to clear to spare teachers a hike in their pension payments. It later adopted a new figure that was just under the limit.

While the board has not explained how the error occurred, an outside consulting firm seemed to take the blame for it in internal documents obtained by The Inquirer and Spotlight PA. The consultant said an employee had made a clerical error.

That said, the bad number was adopted after dissident board members, notably then-State Treasurer Joe Torsella, raised concerns that Grell was using unaudited figures, in a break from typical procedure, to generate the numbers for investment returns.

At the time, board leaders brushed aside Torsella’s warnings.

“We went back and double-checked the numbers,” said board chairman Chris Santa Maria, a history teacher and former union leader in the Lower Merion schools.

He added: “The information is now reliable and defendable.”

“We did our due diligence,” Grossman said. “We covered it. I’m not worried about it.”

WHILE YOU’RE HERE… If you learned something from this story, pay it forward and become a member of Spotlight PA so someone else can in the future at spotlightpa.org/donate. Spotlight PA is funded by foundations and readers like you who are committed to accountability journalism that gets results.