A speech and accompanying lesson plan about the 1918 Bethlehem Steel Baseball League by Geoff Gehman was published on C-SPAN in mid-December.

Gehman, who has no connection to Lebanon County except his “late father loved Lebanon bologna,” recently discussed with LebTown his interest in baseball, the roots of which run deeper.

“My parents, by the way, their very first date was at the Polo Grounds, which was the home of the New York Giants, and they were married 10 weeks later,” Gehman said. “So, baseball has been in my blood forever.”

Gehman himself played baseball for 12 years, ending his career as a pitcher for Lafayette College.

Gehman said he “always had an interest in baseball history growing up in metropolitan New York and knowing all about the Yankees, and the Brooklyn Dodgers, and the New York Giants.”

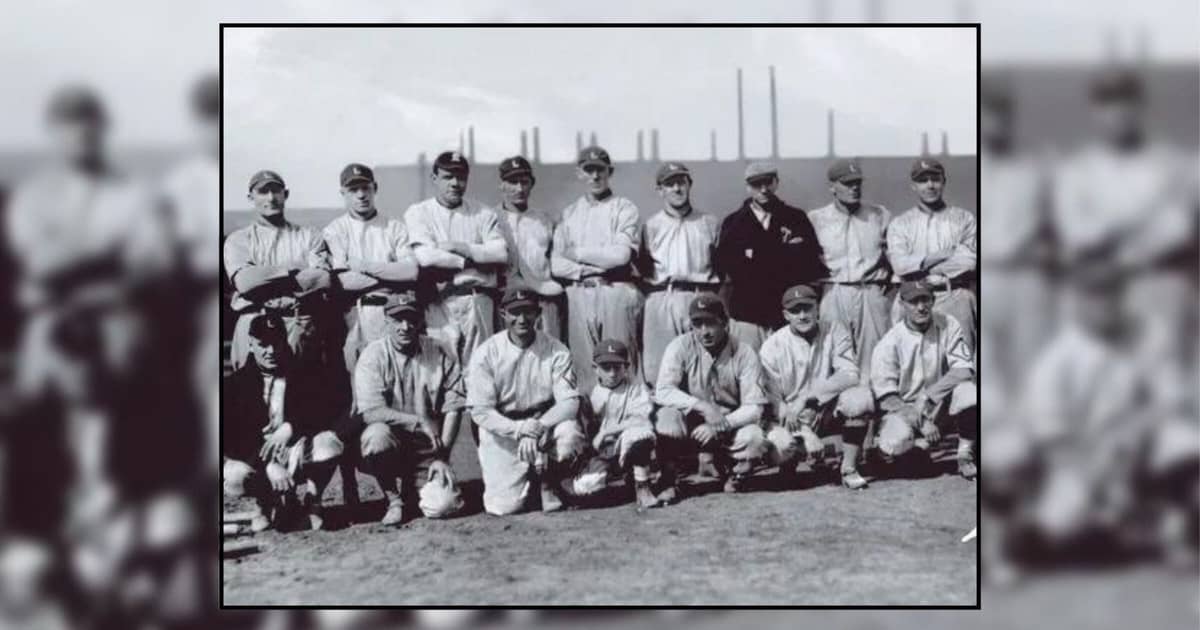

Gehman then explained his connection to a specific period in baseball history, when Rogers Hornsby, Stan Coveleski, and George Herman “Babe” Ruth played in the 1918 Bethlehem Steel Baseball League.

“I’m speaking to you from an apartment in a mansion that was built by a Bethlehem Steel executive in 1900,” Gehman said. “I can see the old steel plant from my apartment. I’m right down the road from Lehigh University, which played a major role in the Steel League.”

Read More: When Babe Ruth played for Lebanon more than 100 years ago

The 1918 Bethlehem Steel Baseball League was also known as the “safe shelter league,” because it provided Major League baseball players an opportunity to avoid the draft declared by the U.S. Secretary of War during World War I by working for a military-essential company.

Sam Agnew, who was Ruth’s catcher on the Red Sox, helped recruit Ruth for the Lebanon team, where Agnew also played as a catcher. Ruth signed a contract on Sept. 25, 1918, for $250 a game, or $500 a week, for the Bethlehem team.

During that same year, Ruth helped the Red Sox win the World Series, which was the reason he arrived late to the Bethlehem Steel League. Because he was late, he never played in an official game. Ruth played in two exhibition games in Lebanon County, in which he did not get a single hit.

“Babe Ruth’s job was he had to deliver blueprints around the Lebanon plant. But according to Gary Gates and people who he’d interviewed, Ruth hardly ever did that,” Gehman said. “His main job – and this is a great picture – he would sit in an office with his legs up on the table. He wore a silk shirt, beautiful shoes, a suit, smoking a big cigar. And he told baseball stories. And basically, he was there to boost the morale of the Lebanon workers.”

The Lebanon plant mainly produced bolts and rivets for warships for the United States and its allies during World War I. In addition to the entertainment Ruth provided, the 1918 Bethlehem Steel Baseball League was itself created by the chair of Bethlehem Steel, Charles Schwab, to promote healthier workers, who were, in theory, more productive workers.

In anticipation of the 100-year anniversary of the 1918 Bethlehem Steel Baseball League, Gehman prepared and ultimately gave several speeches in Bethlehem throughout 2018.

“And last year, the Kemerer Museum in Bethlem decided to have this exhibit about play,” Gehman said. “The director there heard about my talk, and so that’s how I ended up doing the talk for C-SPAN at the Kemerer Museum.”

Gehman, who has three decades of journalistic experience covering the arts and sports for newspapers in the Lehigh Valley, revealed the main sources that contributed to his speeches and lesson plan.

“One of the joys was going to the microfilm at the Bethlehem Area Public Library and looking up 1918 stories in [The Bethlehem Globe-Times], which actually was my very first paper [job] in Bethlehem when I came in 1980, so that was a nice connection,” Gehman said.

Gehman used a reporter from the Globe-Times’ coverage of the games played by the Bethlehem-based team. The 1918 Bethlehem Steel Baseball League was composed of six teams, one from each of Bethlehem Steel’s six plants.

“An equally good source was a newsletter that Bethlehem Steel put out in 1918, mainly for its workers,” Gehman said.

The newsletter informed the workers on who was promoted, ways to prevent themselves from catching the Spanish flu and to ration sugar during World War I, and reports on the Bethlehem-based team’s players.

“For Lebanon, the best source of all was an unpublished book by a guy named Gary Gates,” who is an adjunct professor of religion at Lebanon Valley College, Gehman said. “Here is Gary’s story: He grew up in Lebanon. His grandfather and father worked for Bethlehem Steel. When Gary was a youngster in the 1970s, he worked for two divisions of Bethlehem Steel. So through that, he heard all these stories about Babe Ruth from either people who were there, who worked for the Lebanon plant, or their sons.”

One of the stories Gates heard was about a homerun that Ruth hit at a practice at the Lebanon plant’s baseball field.

“This ball went over the fence. It went over the bleachers. It went over the clubhouse. It went over the creek. It went over a warehouse where Bethlehem Steel workers were watching Babe Ruth hit. And it ended up in the boxcar of a moving train that ended up in Ohio,” Gehman said. “So the joke Gary Gates says is that that was the longest homerun in history.”

Ruth was in the area from Sept. 25 until Nov. 13, 1918. Gehman continued to share about Ruth’s legacy in Lebanon County, where he had three homes, one of which was owned by Bethlehem Steel.

“He crashed into a telephone pole in Lebanon during that time,” Gehman said. “He gave the mechanic a $10 tip for fixing, but he stiffed the mechanic for the rest of the bill.”

Ruth also rang up a big bill at the butcher’s shop in Lebanon County, which he also did not pay.

“There’s no report that I’ve come across that had Babe Ruth enjoying Lebanon bologna, but he should have because he had a big appetite for hot dogs,” Gehman quipped.

“But the best story … is that he had an affair with a lady who lived in Myerstown,” Gehman said. “And he bought her a fur coat to pacify her because allegedly she became pregnant with his child. That’s the biggest mystery of all.

“Eventually, they had a practice at the baseball stadium at the Lebanon plant. And Ruth had promised the youngsters who were there with their dads that he would get them souvenirs,” Gehman said. “So, he had every practice ball out of the stadium, every single one, and he pissed off the manager of the Lebanon team because they didn’t have any more practice balls.”

The manager of the Lebanon team was Charles Schaeffer “Pop” Kelchner, who would go on to become a scout for the St. Louis Cardinals. Pop deemed himself a Christian, so he couldn’t cuss Ruth out for taking all the practice balls. Pop later told the story to a St. Louis Cardinals’ publicist, which is how Gehman stumbled upon the story.

“One of my goals is just to tell the story, to expand it. Even in the biographies of Babe Ruth, there’s very little told,” Gehman said. “And that’s why it took people like Gary Gates, who are part of the community, to really uncover, unravel.”

Gehman said that the target audience for his speech and lesson plan are people who were not able to see the major leaguers in action but grew up sharing stories about baseball legends with others.

“It’s called the old hot stove league. And that’s sort of like a saying for back in the winter … you’d sit around the hot stove in a general store, let’s say, and you told these stories to keep the winter from being so long,” Gehman said. “And that’s the way I try to tell stories is like you’re around the hot stove.”

In addition to the attention-grabbing stories from the period, Gehman noted how the period is a natural teaching tool with its connections to baseball, local history, military history, and sociology.

Ruth left Lebanon County two days after the Armistice, but a Bethlehem Steel workcart now in the possession of the Lebanon County Historical Society shows Ruth was paid through February 1919.

“The war was over. The major leaguers went back to the Major Leagues. Ruth became even more of a hero,” Gehman said. “And the 19 games played in the Bethlehem Steel League in 1918 were sort of forgotten. But thank God, the newspapers and other people kept records of them.”

To those interested in learning more about the period, Gehman recommended reading Gary Gates’ book once it is published. Gehman also recommended reading the biography of Charles Schwab.

Questions about this story? Suggestions for a future LebTown article? Reach our newsroom using this contact form and we’ll do our best to get back to you.

Become a LebTown member.

Cancel anytime.

Monthly Subscription

🌟 Annual Subscription

- Still no paywall!

- Fewer ads

- Exclusive events and emails

- All monthly benefits

- Most popular option

- Make a bigger impact

Already a member? Log in here to hide these messages

Our community deserves strong local news. LebTown delivers in-depth coverage that helps you navigate daily life—from school board decisions to public safety to local business openings. Join our supporters with a monthly or annual membership, or make a one-time contribution. Cancel anytime.