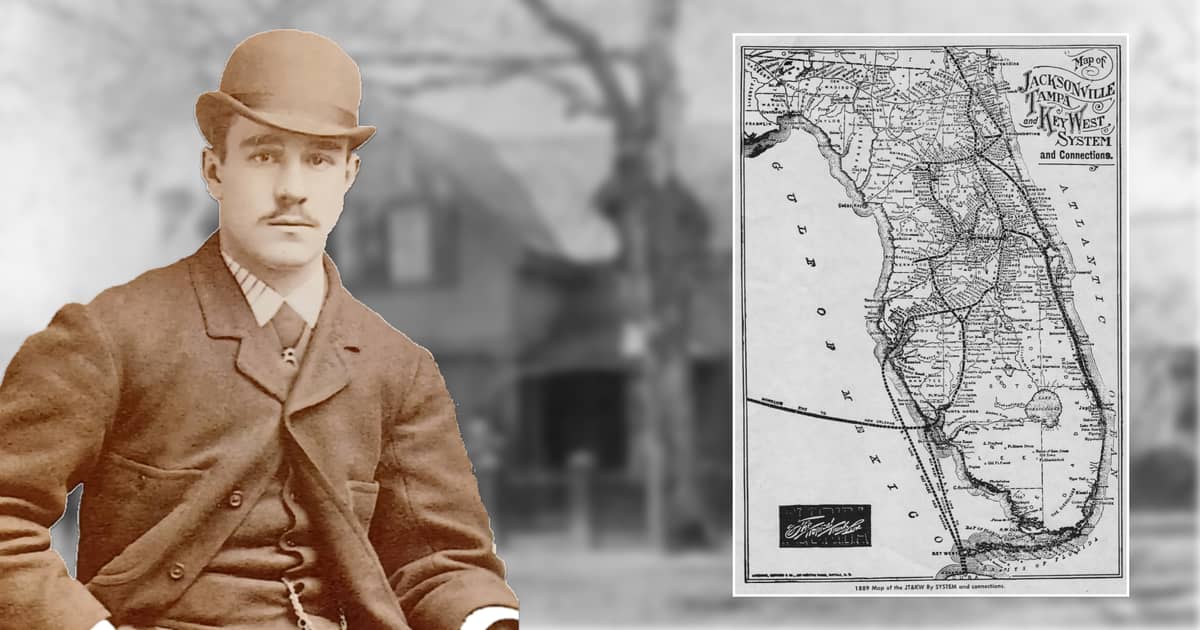

‘Tis the season … when snowbirds fly south to Florida. This is the story of one man, Robert H. Coleman, who made the journey.

Part 1 of this series on the curious life and legacy of Robert H. Coleman examined the circumstances that lured him to risk his vast fortune in Florida.

In this installment, consider the circumstances that shaped the boy who became Lebanon’s “iron king,” with a passion for railroads.

Imagine having to tell an adolescent, who barely understands the value of a dollar, that one day he would be inheriting a fortune worth millions of dollars.

Robert H. Coleman’s mother and his advisers raised and coached him with as much care as they could.

The 30-million-dollar question: Why did the son of an iron family become involved not just with iron (and why not steel), but with railroads? And how could it end so badly?

Voices familiar to him would materialize on the veranda of his Saranac Lake cottage, years later: “Robert, you had it made, wealth beyond imagination. What happened?”

The young man Robert Habersham Coleman was far from the hapless “Florida Man” caricature mentioned in Part 1 of this story.

Though born in Savannah on March 27, 1856, Robert was truly the product of Cornwall, Pennsylvania, for it was the history and wealth of the great Cornwall iron mine that propelled him.

Given the family iron business, one could hope to have found the young boy playing near the open iron pit with his friends, toy shovel and pickaxe in hand. Although there are no photographs or accounts of such play, he did write an essay about iron and other metals in 1869, age 12:

“There are a great many different kinds of Metals, and they are all very useful. The chief and most useful metal is Iron. This metal is so hard and inflescible (sic), that it can only be made into a form by melting it in the hottest furnace that can be found, and then putting it into a molding machine, which will turn it into any shape you please. The other metals …[he proceeds to demonstrate his knowledge of gold, silver and lead] … And now you see that God knew that metals would be of use to man sometime or other, and I trust that as I grow older, I will know more about these useful things.”

We do know (from the story “Anne of Cornwall”) that he was close to his sister and they enjoyed summers in Cornwall. He enjoyed keeping pets. While he was away in New York or Savannah, caretakers looked after his horse in the family stable, along with a dog, rabbits, and the like.

They travelled by horse carriage at least once per week to St. Luke’s Episcopal church in Lebanon and to mid-week Bible studies with his close adult friend, Rev. Alfred Abel.

Rev. Abel was a frequent guest at the Coleman household. Coleman’s mother, Susan Ellen Habersham, probably encouraged that as an influence on her two fatherless children. Abel would routinely enquire of Sue Ellen about Robert’s progress at school and write him encouraging letters. Later, in his final year at Trinity (1877) and having received his inheritance, Robert received a letter from Abel encouraging him to donate to the new diocesan school. Mother followed up, writing to remind him to support this vital work in Lebanon. The following year Abel departed to take up work for several years in Washington before returning to serve at the Children’s Home in Jonestown. The spiritual influence Robert received from Abel no doubt reinforced that of his own mother.

But with father William Coleman having passed away, mother kept the family on the move; travel by train became the norm in Robert’s life. From Cornwall it was common to ride the train to Philadelphia for shopping. Seasonally they would depart Cornwall by train for autumn in New York City. From there, by train to Washington, and to board a steamer to Savannah. By springtime, it was another train and steamer to Europe with cousins, as was the Coleman family custom.

The iron industry may have been ingrained in him (see James Polczynski’s “Souls of Iron”), but railroads were in his blood. Close your eyes and imagine what it felt like as a youth to see new landscapes from a train window. The rhythm of wheels on rails. Or mighty iron sailing vessels rolling on ocean swells, carrying him to the refined trains and trolleys of Europe.

A boy and his toys

Robert received his first train set at age 11 from his guardian, “Uncle (Samuel) Small.” According to a story in the Hartford Courant, he enjoyed orchestrating train crashes then working diligently to restore the damage, as documented by Richard E. Noble in “A Touch of Time,” Noble’s book on Robert’s life.

Sue Ellen had sent Robert off by train to school in Connecticut – the Rectory School in Hamden, under the leadership of headmaster Charles William Everest. The school’s greatest years were in the 1860s, which no doubt is why she sent him there in 1869, finishing in 1873.

He would travel to school by train, and return to New York for holidays, having received instructions in letters from his mother regarding which trains to board, and how to have his trunk shipped. She would routinely send him shipments of necessary supplies, edible treats, and clothing, all by train. In her letters he would alternately be admonished for throwing “paper balls” during lessons, and then doted upon with promises of sending to him his favorite sled.

At age 15 he wrote home requesting a steam engine, which he earnestly wanted to buy with his allowance. He had written home, fascinated that his teacher had made such a steam engine. Mother negotiated, offering him instead a “toy boat” as a present, with hopes that he would leave his money to grow in the bank another year before such a significant purchase. He opted for the boat and within several days she wrote again that the toy was on the way. She also let him know that his gun had been repaired and returned home. All parents can identify with the material needs and wants of their children, a timeless reality.

Young Robert would also have been fascinated with the steam engines at the Cornwall Iron Furnace, the Anthracite Furnace, and the Cornwall Grist mill. Knowing his passion for machines, in another letter Mother mentions “we have a machine for boring the ore hills to find out how deep the iron ore lies. You will be much interested in it I am sure and I hope you will find out all about it and explain it to us.”

In 1873 he returned to Connecticut to attend Trinity College in Hartford, already accustomed to the routine of train travel. Mother’s and sister’s correspondence with him repeated the same patterns as before. By the end of that year he had won the battle of the steam engine, for his mother wrote from Cornwall that not only his engine but also his organ were in good working order and ready for his return for the summer. The engine remained important to him as it was mentioned several times in correspondence the following year. His Uncle John Rae, while visiting Cornwall enjoyed being in Robert’s engine house; “all is quiet,” he wrote, referring to some of his trains.

It was also in his first year at Trinity he spent some of his allowance on a telegraph machine. Much more than a simple telegraph key, the machine was a fascinating contraption enabling both transmission and reception, with a clock-like mechanism for recording the message on paper tape.

Robert understood the telegraph as a necessity as a young person today would understand a cellphone. The telegraph was everywhere: in how many train stations did he see one in operation and how many times did he receive telegrams from home? The Colemans were accustomed to wiring orders for supplies from merchants in and out of town, a precursor to our enjoyment of online purchases.

Mother reacted to the purchase in a letter: “I don’t think you have been too extravagant, except for purchasing [the machine],” and proceeded to exhort him to follow the better example of his roommate. “The only fear I ever have for you is that you may not study enough and may become extravagant.” Prescient words lost on a young man who would finish college near the bottom of his class and later suffer tragic financial failure. An extravagance? Yes, for he would not have been able to connect it to the greater world. Nevertheless he cherished it and savored learning the code that enabled trains and commerce to move.

Prior to his final year at Trinity, the Great Philadelphia Centennial Exposition of 1876 captured Robert’s attention. Anne wrote to him describing its many displays and especially the Machinery Hall that featured all kinds of engines, trains, and an organist providing music, which she thought Robert would especially enjoy.

The exposition has been described as the first world’s fair held in the United States, a grand event presumably patterned after Prince Albert’s “Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations” of 1851.

The Philadelphia exhibition was sponsored by the sale of $10 shares of stock. The following image shows 43 shares issued in 1872 and held by Samuel Small, guardian on behalf of Robert and Anne Coleman.

Like Coleman’s mother, Samuel Small discouraged extravagances but an investment equal to $12,600 in today’s currency was deemed worthwhile to inspire their young minds.

Later, Coleman relived the experience by hosting with others the Florida Sub-Tropical Exposition, promoting commerce for Jacksonville, Florida (1888-1891).

A passion for model trains

In 1877, Robert turned 21, achieving “majority,” which opened up to him the wealth of his inheritance. With his mother’s guidance, in addition to generous contributions to Trinity College, he soon began improvements to “The Cottage,” and built an organ conservatory for himself.

Not only was Robert’s adult life picking up steam in a metaphorical sense, but also in a literal sense through his recreational interest with trains. Enjoying free time when he could, he built a model train shop to house improvements to his model trains, which included tracks on the floor and spectator bleachers for his guests.

In 1879, he contracted with an Atkins Stover of Greenpoint, Brooklyn for three rail cars and repair of his French locomotive for $60 (an $1,800 value today). Additionally, he spent $800 ($24,000) to build a large-scale model engine, which had many working features including a vapor lamp that burned alcohol. The model engine has survived the years, and is believed to remain in the possession of Coleman descendants, and was loaned to be put on display for a period of time at the Lebanon County Historical Society in 1990.

Stover was having difficulty, not with the engine but in tracking down young Robert H. Coleman to have him witness the engine running. Married in January 1879 to Lillie Clarke of Hartford, Coleman and his bride were hard to locate between visiting Europe and honeymooning in Georgia. A letter from Stover finally reached Coleman in Thomasville, Georgia, in June. He provided instructions on operating the boiler, and wanted to know where to make final delivery of the new engine.

Trains as therapy

By the following June, Lillie would be dead. A Lebanon newspaper story gave an account of Robert’s state of mind and the solace he sought with his model trains and his fascination with the technology of the day.

The story was carried in several Pennsylvania papers in 1881:

Article in the Lancaster Intelligencer Journal on Feb. 22, 1881

“Since the death of the young bride the grief-stricken widower has paid much attention to machinery and engineering. He had a building erected containing a single large room, with high ceiling and frescoed walls. A circular roadway, with a double line of steel tracks, extends around the room. Patent safety-switches, electric crossing signals, safety-frogs, and time latest methods of fastening rails are in use on this play-house railway. The total length of the track is about 150 feet, double track, and two sidings. At one end is a roundhouse, with turntables that operate automatically. Three miniature locomotives are employed. Every piece of mechanism, every rod, bolt, screw, lever, spring, tire, cock, pipe, and pump is on these locomotives. The boiler jackets, rods, and drivers are nickel-plated, and some of the bright work is silver-plated. The cabs are of solid walnut, and the boilers proper and the fire-boxes are of wrought steel. The tenders are of copper, and their water supply is taken by scoops from vats on the roadway while the locomotives are in motion. The locomotives are about four feet in length, including the tender, and are models of beauty. They are of English design, so far as high driving-wheels are concerned; otherwise, they are advanced American mechanical ideas, and have many original appliances of Mr. Coleman’s invention. The locomotives are fired up and set in motion. Around the tracks they go, while the millionaire owner watches the movement of the miniature machinery. Hours are thus passed; all sorts of experiments are tried; high speed and low speed compared to determine the comparative effect of friction.”

Trinity College generosity

Robert by no means spent his vast wealth only on model trains and other forms of personal gratification. Having pledged to Trinity’s Delta Psi fraternity, on graduating he donated $28,000 for a new chapter house when the campus moved away from the present-day site of the capitol. He also gave a new organ for the chapel in 1878 and in 1887 donated $10,000 for a new college gymnasium.

Much later, the Trinity College alumni office would memorialize Coleman’s life as divided into two parts of 37 years each: “action” and “exile.” Honored at the time for his generosity and public spirit, after 1893 he never returned to Trinity.

Early business pursuits

Coleman was not simply idling his time of new-found wealth enhancing his mother’s “Cottage,” traveling to Europe, sponsoring the Cornwall baseball league, or tinkering with his model trains. In 1880 he was busy building an exquisite mansion in Cornwall for his new bride. And, he was stepping up to the role of managing business, mostly through his general manager Artemas Wilhelm. In October 1879, the Lebanon Daily News first reported ground-breaking on his two Colebrook furnaces in west Lebanon, managed by Charles Forney. Other correspondence records conversations about researching new hot-blast equipment for furnaces.

Proposals arose for a rail connection from Elizabethtown to Cornwall for transporting ore westward on the Pennsylvania railroad. In June 1882 Coleman would start building his Cornwall & Lebanon railroad in Lebanon, soon employing 800 men to connect it to Conewago; this endeavor also leading to the creation of one of Lebanon county’s treasures, the Mount Gretna campgrounds.

More details on Coleman’s “busy decade” coming next in Part 3. Stay tuned!

Read Part 3 of Robert H. Coleman, Florida Man, here.

Read Part 1 of Robert H. Coleman, Florida Man, here.

Questions about this story? Suggestions for a future LebTown article? Reach our newsroom using this contact form and we’ll do our best to get back to you.

Join our community of local news champions.

Cancel anytime.

Monthly Subscription

🌟 Annual Subscription

- Still no paywall!

- Fewer ads

- Exclusive events and emails

- All monthly benefits

- Most popular option

- Make a bigger impact

Already a member? Log in here to hide these messages

Free local news isn’t cheap. If you value the coverage LebTown provides, help us make it sustainable. You can unlock more reporting for the community by joining as a monthly or annual member, or supporting our work with a one-time contribution. Cancel anytime.