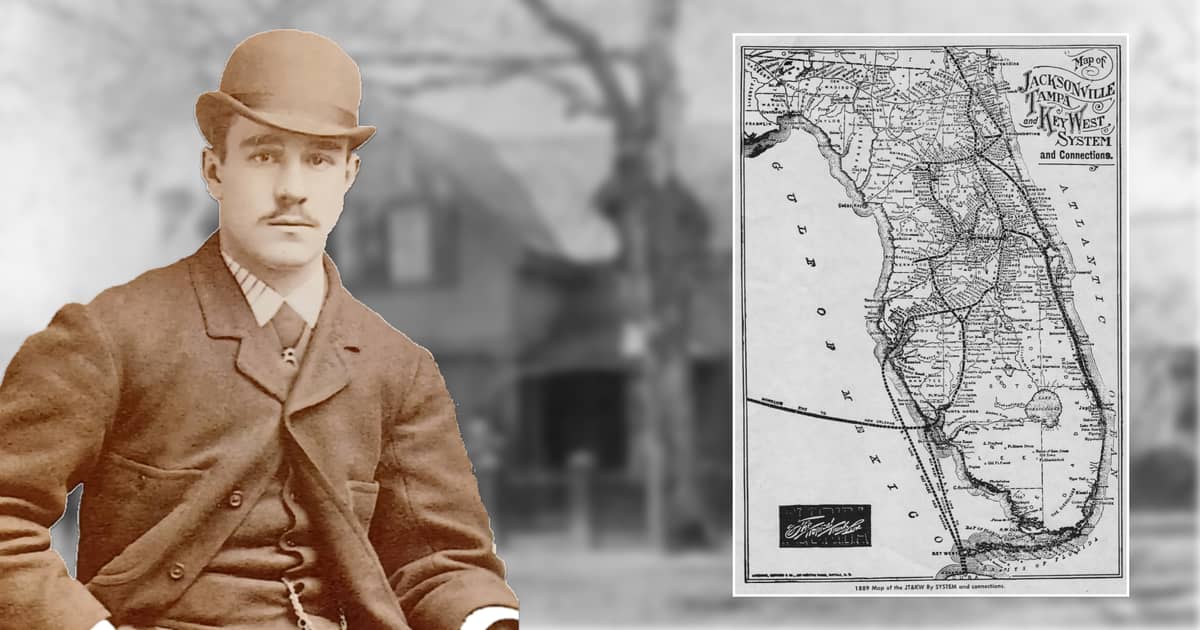

‘Tis the season … when snowbirds fly south to Florida. This is the story of one man, Robert H. Coleman, who made the journey.

Part 1 of this series on the curious life and legacy of Robert H. Coleman examined the circumstances that lured him to risk his vast fortune in Florida.

Part 2 looked at Robert H. Coleman’s upbringing and education, and the early passions that came to play a huge role in his life and career.

In this installment, appreciate the full scope of all Coleman’s activities in Lebanon County during his “busy decade.”

At age 31, Robert H. Coleman was honored at a banquet so elaborate that even the exquisite floral pieces were imitations of his Cornwall & Lebanon Railroad depot and its locomotives.

The dinner, held on the evening of Aug. 2, 1887, was a “testimonial of the appreciation of the citizens of Lebanon of the substantial aid he has given the city in its path of progress by his enterprises and liberality.”

On that evening, 140 gentlemen sat down in the large dining room of the Eagle Hotel under the “brilliance of electric light” and with music by Lebanon’s Perseverance Band. The honored guests included General D.H. Hastings, state Adjutant General, and Gen. Hartranft, commander of the Pennsylvania National Guard, as well as many city officials.

The news story painted a picture of Lebanon’s renaissance, celebrating the old but ushering in a new era thanks to Coleman’s insightful leadership, and praised his easy-going nature.

In his remarks Coleman observed how in seven years Lebanon’s population had more than doubled to 16,000 thanks to the expansion of furnaces, mills, factories, and railroads. He appreciated the friendship of so many citizens, and with their support he expected the city to grow to 25,000 in another seven years. (In fact it took until the 1920s for the city’s population to reach 25,000 thanks to Bethlehem Steel. It remains today at 26,581. The population of the entire Lebanon County is about 143,500, according to the latest U.S. Census figures.)

Nine toasts extended the banquet into the early morning hours, congratulating not only Coleman but celebrating a litany of Lebanon’s excellencies, from industry to education.

How was Robert H. Coleman admired by greater Lebanon? Here is a brief scrapbook of his press clippings:

- Jan. 17, 1877: Artemas Wilhelm, representing the Coleman heirs, donated 500 tons of coal for distribution to Lebanon’s poor, through Lebanon’s Howard Association (a national charity named for British philanthropist John Howard).

- Sept. 10, 1879: Coleman purchased land in Lebanon, to become the location of the new Colebrook furnace, the beginning of various industries that would employ hundreds of workers.

- Oct. 1, 1879: At age 23 Coleman was elected president of the Cornwall Ore Bank Company.

- June 1882: Coleman employed 800 men extending the Cornwall & Lebanon Railroad to Conewago.

- Jan. 30, 1883: Coleman and Mrs. Arthur Brock hosted an exhibition at the Old Weidman mansion on North 9th Street. His 38 items and her 12 (see Profound Possessions story) resulted in significant contributions for the Free Circulating Library of Lebanon.

- June 25, 1884: He sent a carload of plants to residents of the Colebrook furnaces in Lebanon. Thousands of flowers in each yard and garden “evidencing Mr. Coleman’s kindness and interest in his employees.”

- July 2, 1884: St. Luke’s Episcopal Sunday School and choir picnic held at (Coleman’s) Mount Gretna. Coleman gave his laboring men at Cornwall a picnic after the harvest.

- July 9, 1884: Coleman hosted a “grand display of fireworks” in Cornwall, for the gratification of the public.

- Aug. 20, 1884: Cornwall Anthracite Furnace and farm employees with families enjoyed a picnic at Mount Gretna.

- Jan. 28, 1885: Coleman presented a plot of land adjoining the cemetery in Cornwall for the Salem Lutheran Church.

- July 1, 1885: He held a picnic for employees of Cornwall Anthracite furnace and farm hands, with music by the Perseverance Band.

- Feb. 27, 1886: Coleman surveyed 10 lots along the south side of Horseshoe Turnpike, east of Bismarck, for building purposes. The largest lot to be for the Cornwall School District school house, “to be known as the Robert H. Coleman addition.”

Robert found time to relax in his organ conservatory, playing an instrument that he enjoyed in college and even in earlier years. The organ is of course not just any “instrument,” but a piece of machinery with plenty of controls, a wide spectrum of voices, and even a water-powered mechanism in the basement to produce the sounds.

He would host organ concerts for friends, employees, and their families. And in quieter moments he found time to compose at least one hymn, shown below.

Coleman’s admirers marveled how he multiplied his inheritance roughly tenfold in as many years. The key to his success was probably not innate business genius, but his generosity. Just as with his contributions to the buildings of Trinity College, his wealth made him many friends in Lebanon.

The other important factor influencing his success was the wisdom of his advisers, foremost Artemas Wilhelm, and his childhood guardian Samuel Small. His pastor friend, Alfred Abel, having returned to the region, also provided a steadying influence.

Artemas Wilhelm (1822-1887)

Artemas Wilhelm, who died just a month after the grand banquet, had been associated with the Colemans since the 1840s. He and his father built the first hot blast furnaces in America and built the anthracite furnaces in Cornwall. He then designed and built the North Cornwall, Burd Coleman, and Colebrook furnaces.

He became manager of the R.W. Coleman Heirs estate until turning it back over to Robert H. Coleman in 1882. In various correspondence, he provided frequent counsel to young Robert, advising him to balance caution and risk in managing his affairs. Soon after receiving his inheritance in 1877, while still in Connecticut Robert sent Wilhelm a check for $5,000 as a “token of his esteem for all that Wilhelm had meant to him and the family.” Wilhelm responded with profuse thanks and hopes to speak with him at Cornwall regarding various business interests.

For the next few years Robert leaned on his adviser for all manner of advice, including the purchase in December 1877 of a seemingly frivolous set of elk heads and antlers. That same month Wilhelm wrote to mother Sue Ellen, thanking her for another cash gift (he had been managing the renovations to her “Cottage”) and acknowledging the transition of their business arrangement from her to Robert, “for whom it will be my great pleasure to watch his interests carefully as I have done since he was a child. Now that he has attained manhood, I feel more than ordinary solicitude for his successful career through life, situated as he is, with a very kind heart, and large means, he will need the counsel of good friends and I shall ever be ready to aid him with advice in every way that I can.”

By the end of the same month, acting as his power of attorney, Wilhelm encouraged Robert to be present in January for stockholder meetings of the Cornwall Railroad and the Cornwall Turnpike. Samuel Small would be vacating his seat as director so that Robert could be elected in his place. This may be the beginning of Robert’s introduction to business (even so Robert remained busy enjoying his wealth, with elk heads, purchasing an $8,000 water-powered Roosevelt organ for his conservatory and buying Christmas gifts for friends, including a ring for cousin “Minnie” – Margaret Coleman Freeman).

The following year (September 1879), Robert was also elected president of the Cornwall Ore Bank Co.

Robert began receiving unsolicited requests from strangers for charitable donations. Fortunately, he was wise enough to confer with Wilhelm, who congratulated his caution, replying “no one who is not possessed of the brass of Satan would ever assume to address such a communication to a stranger. I am glad you view it in its proper light. If you ever commence similar donations, you will never live to see the end of them.”

Wilhelm was at the ready with other financial advice, such as recommending a low-risk secured loan of $25,000 to Wm. Kaufman for his firm at Sheridan furnace. Wilhelm continued to manage the furnaces for the family, corresponding as financial secretary to Robert by sending his $23,000 share of surplus funds from sale of iron but warning him that the market was depressed.

The abundance of correspondence between Coleman and Wilhelm, too much to cover here, merits a story of its own. For now, this: Artemas Wilhelm congratulated Robert for having written a corrective letter to architect McArthur “which was certainly definite and to the point. You will soon begin to learn of the effort and patience required to get work done properly. My experience is that it requires pressure and ‘Eternal Vigilance.’”

It was not Robert’s personal business acumen but the strong voice of his wealth that kept the attention of those working for him. The familiar adage “surround yourself with skilled people” was his secret for his early success.

This advice had come directly from Wilhelm (April 1880): “My further advise (sic) is don’t you ever undertake the management of the details that can only be done by those whose constant and unremitting attention is required. You will have most ample to do by giving general advice and a general supervision over your individual as well as your joint interests. Your trusteeship will also add to occupy your time and labor. Many men would say that interest alone is enough for any one man to look after.”

Although there is a view that Wilhelm and Small disagreed on advising Robert, Small being conservative (“always protect the principal, invest the profits”) and Wilhelm advising calculated risks, they were nonetheless good friends. However, Wilhelm wrote Robert in 1879 while encouraging him to enjoy his income to not forget “the advice I have always given you: Spend your income but kept the principal unimpaired for any emergency which may arise and you will always be in a position to protect yourself.”

In April 1880 Wilhelm writes concerning a disagreement between Robert and his Freeman cousins, that the Coleman business strength was the harmony of family members: “I will always advise harmony and united interests … which underlie your impregnable strength.” In the same letter he mentions having a delightful visit from Samuel Small, staying at his house for a short time.

Samuel Small

Robert’s guardian Samuel Small, a successful York businessman, admonished Robert to be judicious in his dealings. He was told to protect the principal of his inheritance as there was plenty of income to finance his endeavors.

When Robert’s southern grandfather Robert Habersham died in 1870 (when Robert was 13 years old), Small writes: “No doubt you have heard of the death of your Grandfather, a man who was highly esteemed and respected for his virtues, a man who was ever ready to do for the poor or anyone in need.”

Small was also a good business man (see this history of P.A. Small & Co. in York, as well as this one), therefore he urged Robert to copy his example, given his own fortunate position; and not be “careless, dissipated, fond of frolic … I expect a great deal from you, believing that you will be sober, honest, industrious, kind to all around you, a man capable of conducting any business. To this end you will not lack the means. God gives it to you as a Steward, and he will have you improve the talent he has committed to you.”

A few years later when Robert attended Trinity, Small encourages Robert to learn well at college and “make his mark in the world,” whether mechanical, scientific, or religious. He warns against “sensual” pleasures and reminds him of Psalm 37. He exhorts further, “My dear Robert the works at Cornwall will be a source of study for you.”

And on entering his final year, Small’s advice to Robert about the significant wealth he is inheriting, “I would advise saying nothing about it to anyone, except your Mother, and avoid every manner or remark which might give persons an idea that you are elated or purse proud. There is so much for a young man in your situation to withstand by way of arrogance and temptation, that everything should be done to give no occasion. … College life I have always thought was a dangerous one, full of Sinning. The Bible says, ‘Stand not in the way of Sinners nor sit in the seat of the Scornful.’ I am very glad to hear from you and should you want more information in regard to the Estate I will give it you with pleasure as far as I know. Pray to Our Heavenly Father for wisdom to guide and direct you.”

Small continued to advise as power of attorney on some financial affairs for several years after Robert attained his majority in 1877, possibly until his death in 1885. He encouraged the prenuptial agreement to protect sister Anne’s finances in marriage. Small frequently encouraged Robert to remain true to his Christian faith, shaping his business decisions on religious principles.

When Robert (or his mother) had disclosed plans for the new house to be built in Cornwall, Small worried, “I fear you are going to make a mistake by building it too large.” From the vantage point of 2023, we watch in horror as he overextends.

Robert H. Coleman, Pennsylvania Railroad man

As mentioned, in 1878 Coleman’s advisers steered him to a director’s chair on the Cornwall Railroad, a company established 1850 as a collaboration by his father William Coleman and G.D. Coleman of Lebanon. They had joined forces to ensure the transportation of Cornwall iron ore to the Union Canal and to the North Lebanon furnace.

Wilhelm reported to Robert that he had been in communication with the Pennsylvania Railroad in 1880, which wanted to build a connector from its line near Elizabethtown via Colebrook to Lebanon. He convinced the officers of that railroad to give Coleman control of the project. This led to the establishment of the Colebrook railroad, providing more efficient transportation of Cornwall ore west to Pittsburgh.

At the same time, Coleman was establishing his Cornwall & Lebanon railroad to enable transportation of Cornwall ore to his new Colebrook furnace. The two projects soon merged, and Coleman became president, the primary shareholder.

Work on the railroad to Conewago from Cornwall began in 1882 and finished October 1883. By the following year the picnic grounds were being developed at Mount Gretna, and in 1885 Coleman provided land for the first National Guard encampment.

Coleman found time to tinker with the features of Mount Gretna, including damming Conewago Creek to form Lake Conewago, and adding amusements that included a steam-engine operated merry-go-round called “The Flying Menagerie.”

The stories of competition between the Cornwall and the Cornwall & Lebanon railroads are well known (see for example the Cornwall National Guard Riot). The tracks of the two companies originally had crossed peacefully in Cornwall, although with two separate stations. Arguments over safety and maintenance of the crossing led to Coleman erecting Cornwall’s train bridge and the elevated grade heading southwest to Mount Gretna.

Robert H. Coleman, inventor

As historian Jack Bitner reported, Coleman’s experiments in his workshop on steam engines led to the idea of erecting the narrow-gauge railroad to the summit of Governor Dick. Surveying begin early in 1893 and by the end of June the road was completed and ready for the grand opening on July 4th.

It was immediately popular; and tens of thousands of passengers rode the train in 1893 and 1894. The excitement wore off quickly and several accidents caused the road to the top of Governor Dick to be abandoned at the end of the year. (Robert himself was already removing himself by this time to Saranac Lake.) The portion of the Mount Gretna railroad that served the National Guard and the rifle range operated until 1915 and was torn up in 1916.

In his spare time Coleman took on the serious problem created by sparks exhausted from the stacks of his wood-burning steam locomotives. Various historical reports describe trains erupting showers of sparks. In the early years of railroads passengers in open cars would have to help one another dampen fires in their clothing. In 1800 Harvard professor Charles Sargent had reported the third leading cause of forest fires was cinders and sparks from passing locomotives.

Coleman worked the problem, eventually coming up with a design for a spark arrestor for which he received patent #387,623 dated Aug. 14, 1888, “Method of Promoting Combustion and Extinguishing Sparks,” a three-page document explaining the concept of his design, which was for wood-burning locomotives. The benefit was two-fold, improving fuel efficiency and greatly reducing the emission of sparks.

Truly “necessity became the mother of invention.” In January 1888 he wrote a letter to the Baldwin locomotive company explaining his experiments. The JT&KW was the only road in the South using the front end with straight stack with wood for fuel. The spark problem was pressing them to abandon that type of engine, but they had a fleet of 20 such locomotives to keep in service.

He had Engine No. 9 sent to the shop as a prototype for experiments in Florida. Meanwhile in Cornwall he was having the design put into one of the Cornwall & Lebanon locomotives to test the efficiency of the concept on a coal-burning engine.

In July 1888, the General Superintendent of the JT&KW in Florida wrote to Coleman at Cornwall reporting on progress, and that his engineer E.T. Silvius was making progress with experiments and adjustments to the design. Within a month’s time, the patent was awarded.

Robert H. Coleman, bank president

In 1884 (age 28) he erected an exquisite building in Lebanon to house the offices of his railroad company, his Colebrook furnaces, and the bank of which he had become president.

Lebanon’s Dime Savings Bank was organized March 14, 1871, at the southwest corner of 8th and Willow streets. Coleman had been a director of the bank since June 1879 when Wilhelm purchased 93 shares for him from the retiring president. After he built this new building at 8th and Cumberland, the bank moved two blocks down. The following year the bank petitioned to change its name to Lebanon Trust and Safe Deposit Bank.

The newspapers raved over the architectural beauty of the building: Its brilliant electric lights were not powered by water, but by a steam-driven dynamo; steam also being the source of heat. In addition to its sturdy limestone foundation, the building and its vault were fireproof, assuring its depositors of the security of their savings.

Winding down…

Boyd’s Lebanon City Directory 1891-93 listed Robert H. Coleman as president of the Lebanon Trust and Safe Deposit Bank, the Cornwall & Lebanon Railroad, and the Lebanon Iron Co., as well as “proprietor of Colebrook Furnaces, Offices and safe deposit vaults, at 8th and Cumberland.” In addition to these achievements are the development of Mount Gretna, his farms and livestock, interest in several racehorses (the subject of a future story), his recreational baseball team, and hosting the Pennsylvania National Guard.

If all of Coleman’s activities in Lebanon County don’t make your head spin, consider that as early as 1881, having lost his young bride just a year before, he ALSO involved himself in land and railroad development in Jacksonville, Florida.

In 1889 the Lebanon Daily News cited an article in The Forum, placing Coleman in the $30,000,000 class, ahead of J.P. Morgan, Marshall Field, A.J. Drexel, and F.W. Vanderbilt, among others. Oddly, history books, and an internet search of “industrial tycoons of the 1890s” fail to mention him.

Stay tuned for the next part of this series…

Read Part 4 of Robert H. Coleman, Florida Man, here.

Read Part 2 of Robert H. Coleman, Florida Man, here.

Read Part 1 of Robert H. Coleman, Florida Man, here.

Questions about this story? Suggestions for a future LebTown article? Reach our newsroom using this contact form and we’ll do our best to get back to you.

Keep local news strong.

Cancel anytime.

Monthly Subscription

🌟 Annual Subscription

- Still no paywall!

- Fewer ads

- Exclusive events and emails

- All monthly benefits

- Most popular option

- Make a bigger impact

Already a member? Log in here to hide these messages

Quality local news takes time and resources. While LebTown is free to read, we rely on reader support to sustain our in-depth coverage of Lebanon County. Become a monthly or annual member to help us expand our reporting, or support our work with a one-time contribution. Cancel anytime.