‘Tis the season … when snowbirds fly south to Florida. This is the story of one man, Robert H. Coleman, who made the journey.

Part 1 of this series on the curious life and legacy of Robert H. Coleman examined the circumstances that lured him to risk his vast fortune in Florida.

Part 2 looked at Robert H. Coleman’s upbringing and education, and the early passions that came to play a huge role in his life and career.

Part 3 explored the full scope of all Coleman’s activities in Lebanon County during his “busy decade.”

In this installment, learn how Coleman’s Florida exploits lead to his undoing.

An earlier account from February 1881 (see Part 2 of this series) described Robert H. Coleman as managing his grief within the solitude of his model train workshop. But in addition to all that he was undertaking in Cornwall and Lebanon, later that same year his attention was drawn to land and railroad development in Florida.

As mentioned in Part 1 of this series, the Florida state government was offering incentives to spur development, namely: a railroad company was granted 13,400 acres of land for every mile of track laid. Investors, including Coleman, found this a proposition not to be missed.

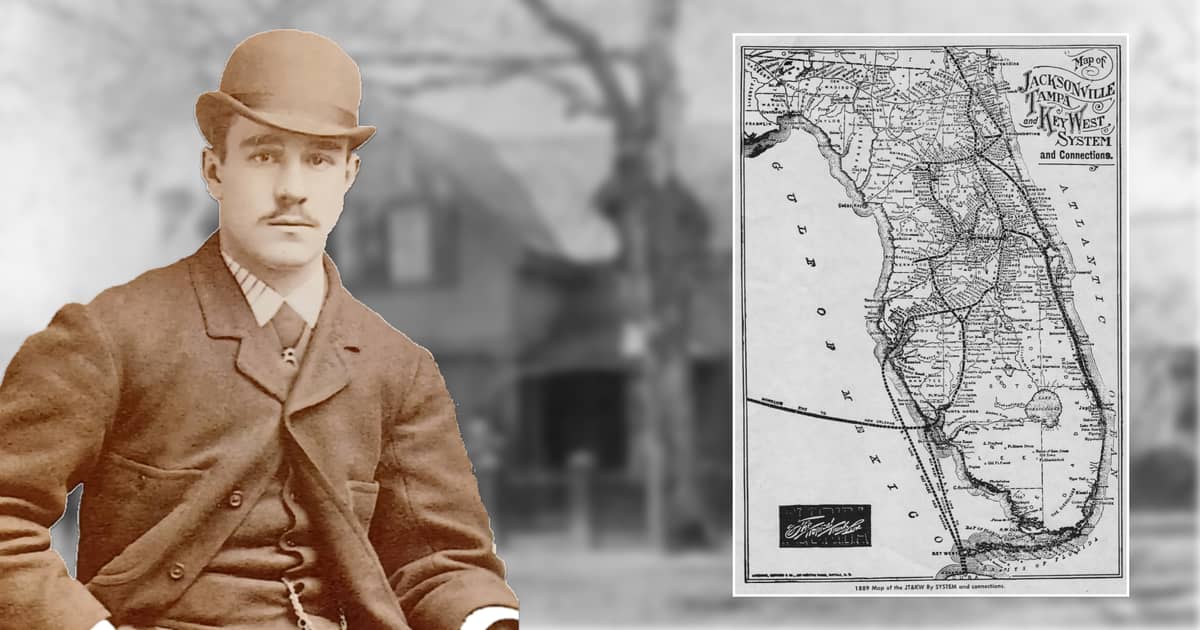

Robert H. Coleman had become a director of Flagler’s Jacksonville, St. Augustine and Halifax railroad, chartered in February 1881. Over the years they would meet often at Flagler’s Ponce de Leon hotel.

Another railroad, the Jacksonville, Tampa, and Key West (JT&KW), incorporated 1878, had been a modest success, its route following the St. Johns River, offering direct competition with the steamboats, but faster and with greater connections to more distant points. The low cost of water transportation forced the company to keep its rates low, but the JT&KW had grown enough to pose a threat to Flagler’s small Jacksonville, St. Augustine and Halifax railroad that served his hotel empire, so through various stock trades he gained control and merged it into his company.

According to George Pettingill’s “Story of Florida Railroads” the new company incorporated June 27, 1881, with $2 million of capital and Robert H. Coleman heading the organization as president. It began surveys of a road from Jacksonville to Palatka, construction of which began in March 1883, with the road operating by March 1884. The company would open more lines in the coming years.

The young railroad president enjoyed favorable press in Florida. A reporter found him in his office in his home at Duval and Market streets to answer a question about a new office building for the railroad. Coleman was “a very agreeable and entertaining talker” able to answer pointed questions with confidence and optimism about the benefits of capital investment to the growth of Florida, for the benefit of everyone.

Board members of the JT&KW formed the separate Florida Construction Company (FCC) which sold needed materials and rolling stock to JT&KW. Coleman subscribed to a significant number of shares in the FCC, investing $365,000 in March of 1883.

The JT&KW prospered and had acquired 1.5 million acres as it expanded. The line to Palatka was prospering soon after it opened in 1884. The discovery of phosphate in Florida led to significant mining operations, requiring ongoing improvement of the railroads for transporting the material. With the assistance of Henry B. Plant’s investment company, the line across the state to Tampa was JT&KW was completed that same year.

One newspaper account St. Louis Globe-Democrat, 24 May 1886 praises the “enterprising capitalists of the north” for developing the state of Florida, improving drainage, building roads and communities, employing thousands of laborers. Calling them “true missionaries to the south,” it cited in particular the directors of JT&KW, including Charles C. Deming and Robert H. Coleman. The latter, the largest stockholder is described as “quite a young man, who possesses marked ability and aptitude for railroad management, as shown by his judicious investments in railroad properties in the north and south.”

Mounting challenges

There was always pressure on the railroads: competition from rivals, ongoing rate negotiations with Florida’s Railroad Commission, and the yellow fever outbreak in August 1888. The epidemic caused many deaths in Jacksonville. As in our recent 21st century pandemic, wild theories were proposed to fight the spread of germs, including fumigating the trains and finally halting train service to Jacksonville entirely.

Nevertheless, the company mostly prospered until the financial depression of the 1890s weakened its finances, further complicated by severe weather freezes. Flagler would pull out, in favor of protecting his other enterprises and leaving the JT&KW on its own.

In 1889, JT&KW director Mason Young wrote to Coleman advocating that they float additional financial bonds to cover their risks. The company had already become over-extended later in the 1880s and came under scrutiny for its financial dealings such as the dealings with the Florida Construction Company.

By late 1892 the Florida Construction Co. was in trouble, with $1.8 million in debt. The management of the company was accused of improprieties: not meeting regularly, nor reporting on their financial condition.

Finally legal action and a court-ordered receivership in 1893 ordered the sale of the JT&KW in 1894, though no buyer was found until 1899 when the Plant System purchased it at a significant discount for $600,000 (in 1891 JT&KW had been worth about $12.6M).

Interpersonal dynamics hint of trouble

It would be interesting to know how a much older Flagler and Coleman had become acquainted, setting Coleman’s Florida ventures in motion. Flagler was among other Wall Street investors in New York City seeking opportunity in Florida. Possibly they met through a common associate that Coleman knew from Trinity College or a fraternity brother.

The connection may have been initiated through Charles C. Deming, attorney at 120 Broadway, New York. Deming was from Hartford, a few years older than Coleman, and attended Yale, not Trinity. He served in various positions as director and treasurer in Flagler’s railroad company. Coleman and Deming served together on the board of directors.

Another power-player in Coleman’s Florida business circle was William H. Barnum, Connecticut politician and industrialist (cousin to showman P. T. Barnum) who became the longest serving chairman of the Democratic National Committee.

Correspondence between Deming and Coleman in December of 1883 sheds interesting light on Coleman’s state of mind. He seemed to be getting cold feet with the Florida business ventures, possibly overwhelmed balancing the demands of managing his extensive interests both in Pennsylvania and Florida.

Coleman had subscribed to at least $50,000 in stock for the next JT&KW venture. Rather than fulfilling his obligation he had pressed Deming to find someone else to purchase the stock. Deming tried several others but was unsuccessful, raising Coleman’s ire. In response Deming writes heatedly, “my first impulse was to retort in a similar vein and if I hadn’t been endowed with an angelic temperament I should have done so.” Deming goes on to defend himself and to suggest the burden was on Coleman to make good on his commitment, or “get some of your Philadelphia friends to relieve you of the burden.”

This may have been the watershed moment that led to Coleman’s failure. Pressures were mounting, and the cautious voices of Robert’s earlier mentors were encouraging him to slow down. But the influence of Deming and the fear of disappointing Henry Flagler spurred Coleman ahead. After all, he had stepped up to the plate, playing in the big leagues with Flagler and Plant. To back down would be to lose face.

In a second correspondence just two weeks later, an unsettled Coleman asked Deming to act as his attorney in managing some of the daily affairs. “My Dear Bob,” Deming responds, “After you get to Florida, I think your interest in the railroad will revive to such an extent that you will not want anyone to attend to your large interest for you…”

Deming’s letter goes on to mention that they had bought the Palatka contract for $143,000 in Construction stock (and confirming the point about the risky business of juggling assets to finance their investments).

Robert was in Cornwall at the end of 1883, but a brief article in the Lebanon Courier dated February 12, 1884 mentioned “Robert H. Coleman starts for Florida today where he will spend a few weeks. He has railroad interests there.” Indeed.

Robert H. Coleman, remarried

The second part of the Florida story concerns Robert’s brand-new family, which divided its time between Cornwall and Jacksonville. He had married his lifelong friend Edith Johnstone in October 1884, and in six years their marriage produced five children.

First in 1885 was Robert, who with two of his brothers later served in Europe during World War I. Next, born in 1886 was William Cassat, then Ralph Elliott in 1888. The youngest son Neyle Habersham was born a year later in 1889. Their only daughter, Anne Caroline came in 1890.

While up north, the family lived in Cornwall Cottage with grandmother Sue Ellen. Photographs from Robert’s personal album confirm that the family accompanied him to Florida. And how did they travel between Pennsylvania and Florida? By private rail car!

Traveling in style

Beginning around 1880, Henry Plant had been known for moving about Florida in his private car, “Car 100,” which served as his rolling office and quarters. In 1886 Henry Flagler specified the design of his own private rail car, “The Rambler,” built by the Jackson & Sharp Company of Wilmington Delaware, for travel between his New York and Florida homes, among other destinations.

Soon after in June of 1887 Coleman followed suit, contracting with the same company for his own private car, to be named “Cornwall.” Its design imitated the details of another private car “Minerva,” named for the wife of Asa Packer of Mauch Chunk (today’s Jim Thorpe), Pennsylvania. Coleman took pains to ensure that the elegance of his car exceeded that of Flagler’s “Rambler.”

In addition to three staterooms, two bathrooms and a kitchen, the car had a wine cellar, parlor, and observation room. Interior features included walnut and oak paneling, mosaic flooring and carpeting, annunciators, chandeliers and other electric lights, down to the provision of china, linens and kitchenware. It was to be painted in the colors of the JT&KW railway.

Coleman was urgent to take delivery by October of that year for a “maiden voyage” with the family to Tampa to confirm every aspect of the car’s intended luxury.

The first picture above shows the car on a siding by the present-day “Root Beer Barrel” located at the Lebanon Valley Rail Trail’s trailhead in Cornwall. The car made many trips, including one to Niagara Falls in 1888 (a few months after the “Pinkerton Affair” in Cornwall). The next picture shows Coleman’s family visiting San Diego.

His prized car is listed with the Delaware Bureau of Archives for the Jackson & Sharp Company, 1888. Unfortunately, he would not ride it to Saranac Lake in 1893, as it was among many lost assets.

Following his Florida peers, Coleman also enjoyed traveling in style on the canals and St. John’s River on his boat, the “Seminole.” In 1884-85 he corresponded with Pepgrass & Pine of Chicago regarding bids and costs for repairs. The work entailed repairs to the hull, boilers, and engine, and renovation of the cabin. The correspondence became quite testy when their costs escalated, having failed to negotiate a contract prior to commencing the work. Repairs were about $1,000 beyond the $2,500 estimate.

Coleman joined Philadelphia’s “Corinthian Yacht Club,” registering the Seminole (length 44, beam 7.5), ported in Jacksonville, and the “Sandy Fly” (length 16, beam 7.6), ported in Philadelphia.

Robert H. Coleman, Florida landowner

Robert was interested in land as much as he was railroads. He and Edith investigated development lots, in April 1888 purchasing acreage in the “Spring Garden” tract of Volusia County, east of the St. Johns River. It had been part of the DuPon-Gaudry Grants from the Spanish Grants of 1807. Records show two purchases, 210 acres of lakefront for $20,000, and then another 168 acres he may have intended to subdivide and sell for profit.

On the lakefront property he had in mind building a great southern mansion, of the Spanish Renaissance style. Bear in mind “Cornwall Hall,” his northern mansion was also under construction at the same time in Cornwall for Edith and their new family; its exquisite architecture to rival that of his sister Anne’s great mansion in Hyde Park, N.Y. Apparently one mansion would not suffice. Whether that was Edith’s request, or Robert betraying his pursuit of extravagance is not known.

This southern mansion, designed by Hewitt Architects of Philadelphia would rival that of Flagler’s hotel, with its expansive features and long veranda. There is no record of it actually having been built, as Robert’s finances were beginning to feel the strain late in that decade. Court records show that in 1893 he defaulted on the properties, which then transferred to his brother-in-law Archibald Rogers and Henry Kendall of Reading.

Disaster Unfolds

According to Federal Reserve History and other sources, the panic of 1893 was one of the worst financial crises in our history. It was triggered by a variety of factors: recession overseas, the McKinley tariff act, falling US gold reserves, increasing defaults on loans. Many banks throughout the country suspended operation. The Philadelphia and Reading Railroad was one of two major railroads that had collapsed, causing major unemployment, disrupting businesses and creating panic in the stock market. With the optimism and industrial growth of the previous two decades, businesses had over-extended themselves, borrowing money for expansion and unable to pay when banks called in loans. More than 15,000 businesses closed during the panic.

It is fair to say that Robert H. Coleman, swept along by the optimism of expansion, forgot the admonitions of his mentors. He also forgot the economic lessons his family had learned in recent decades. The family had been nearly insolvent in the late 1850s, at which time Artemas Wilhelm had been retained to manage their iron business. Early in the 1870s the Cornwall furnaces had been taken out of blast because Congress removed the tariffs that had enabled competition with the low price of iron from Europe. In mid-October 1873 Mother wrote to Robert in college to conserve his allowance: “Mr. Wilhelm was here this morning and looks very blue about money matters. I feel sorry for him. He is so conscientious in all he undertakes. It must be hard for him to stop the work on the Byrd Coleman [sic] (furnace) and blow out the others, but then there is no iron selling and there will be no use in making it.”

Collapse

The Lebanon Daily News reported on August 8, 1893 that Coleman assigned his financial affairs “for the benefit of his creditors” to brother-in-law Archibald Rogers of Hyde Park and Henry T. Kendall of Reading, a long-time trusted agent. The article referred to a collection of both news reports and letters to the editor, mostly expressing sympathy for Coleman, still greatly beloved for his charity to Lebanon. The cause was attributed to his over-extension to the Jacksonville, Tampa and Key West railroad, compounded by the financial strains in the country.

A separate article from the day before reported the sale of “Coleman’s vast interests” to the Lackawanna Iron Company of Scranton, for three million dollars. These assets included his 15/96th share of the ore banks, two anthracite furnaces in Cornwall, two Colebrook furnaces (in Lebanon), controlling interest in his Cornwall & Lebanon railroad and a 125 acre farm connected with the Anthracite furnaces. He retained his home in Cornwall, and the Colebrook estate (including Mt. Gretna) as well as two farms, one in Cornwall and one in Bismarck (Quentin). His net worth was estimated at $5.1 million (whereas previously his assets estimated at various times from $20 to $30 million), which was considered twice the amount to cover all of his debts.

Earlier warnings

Previously, in July of 1892 the Lebanon Daily News reported that Robert H. Coleman had resigned as president of the JT&KW, the C&LRR, Lebanon Iron Works, and the Lebanon Trust and Safe Deposit bank. The reason given was Edith’s ill-health. They were boarding their private “Cornwall” car for New York where they would board a French steamer “La Champagne” for Havre. Given the hopes for her improvement in France they estimated staying two or more years. Archibald Rogers and Henry Kendall, long-time associates, were to look after his affairs during his absence.

The exodus

The story doesn’t end there. Robert H. Coleman was only 37 when his financial empire collapsed.

Coleman had already moved his family out of Coleman Cottage and they were living temporarily in the Superintendent’s house of the Anthracite Furnace in Cornwall. Then, according to reports, he loaded the family and some belongings in a carriage and headed out of town. In a Lebanon newspaper story (May 19, 1894 “Still Traveling Northward”): “Robert H. Coleman and family, who spent Thursday night at Pinegrove, stopped at the Eagle Hotel, Edward Hummel, Proprietor. Yesterday morning he started for Pottsville which he reached last evening.”

A subsequent article (Lebanon Daily News, July 8, 1894) characterized their journey as a “pleasure trip overland, have reached the Adirondack mountains. Mr. Coleman writes that the trip has been an enjoyable one and that himself and family are enjoying excellent health.”

Finally (Lebanon Daily News, 16 Oct 1894 “Sojourning at Lake Saranac”) “Robert H. Coleman and family, who have been spending the summer in the Adirondacks, have left there and are now sojourning at Lake Saranac. They will spend the winter there with other families of their acquaintance.”

Our local newspapers maintained a rosy outlook for the Coleman family, seemed to forgive any failing that kept them away from Lebanon County, and expected their eventual return. Between the humiliation of failure, and growing concerns for Edith’s health, it eventually became clear that their departure was permanent.

Robert H. Coleman never returned to Lebanon. More in the final installment of this series, in which we will be ushering in the new year with “Coleman’s new life in Saranac Lake, New York.”

Read Part 5 of Robert H. Coleman, Florida Man, here.

Read Part 3 of Robert H. Coleman, Florida Man, here.

Read Part 2 of Robert H. Coleman, Florida Man, here.

Read Part 1 of Robert H. Coleman, Florida Man, here.

Questions about this story? Suggestions for a future LebTown article? Reach our newsroom using this contact form and we’ll do our best to get back to you.

Support Lebanon County journalism.

Cancel anytime.

Monthly Subscription

🌟 Annual Subscription

- Still no paywall!

- Fewer ads

- Exclusive events and emails

- All monthly benefits

- Most popular option

- Make a bigger impact

Already a member? Log in here to hide these messages

Local news is a public good—like roads, parks, or schools, it benefits everyone. LebTown keeps Lebanon County informed, connected, and ready to participate. Support this community resource with a monthly or annual membership, or make a one-time contribution. Cancel anytime.