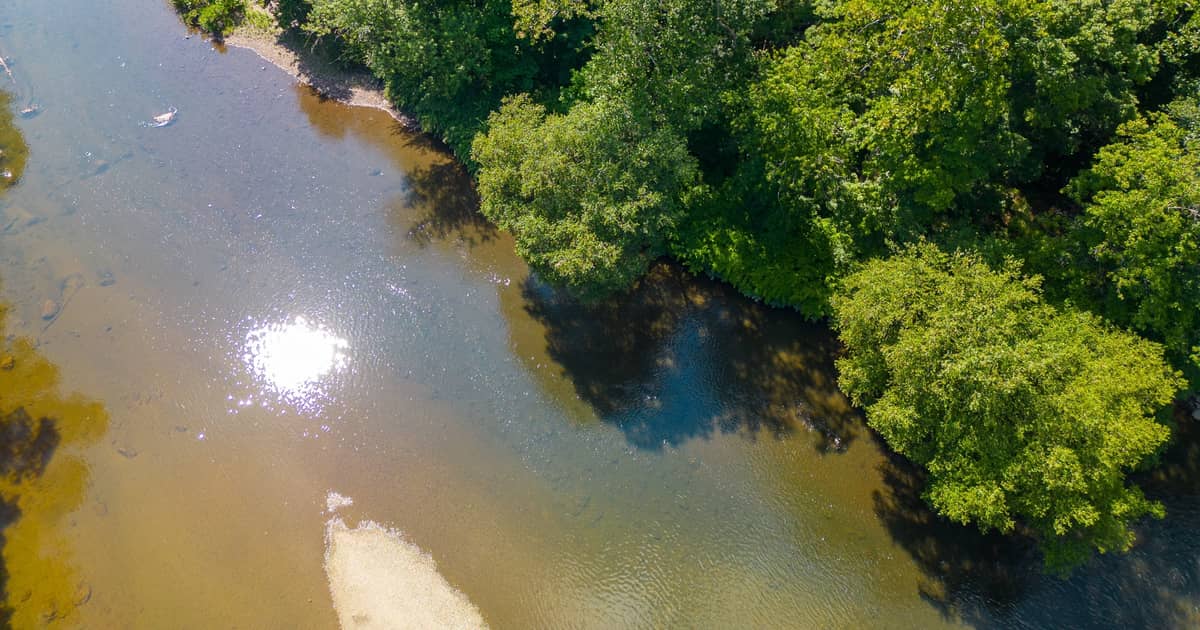

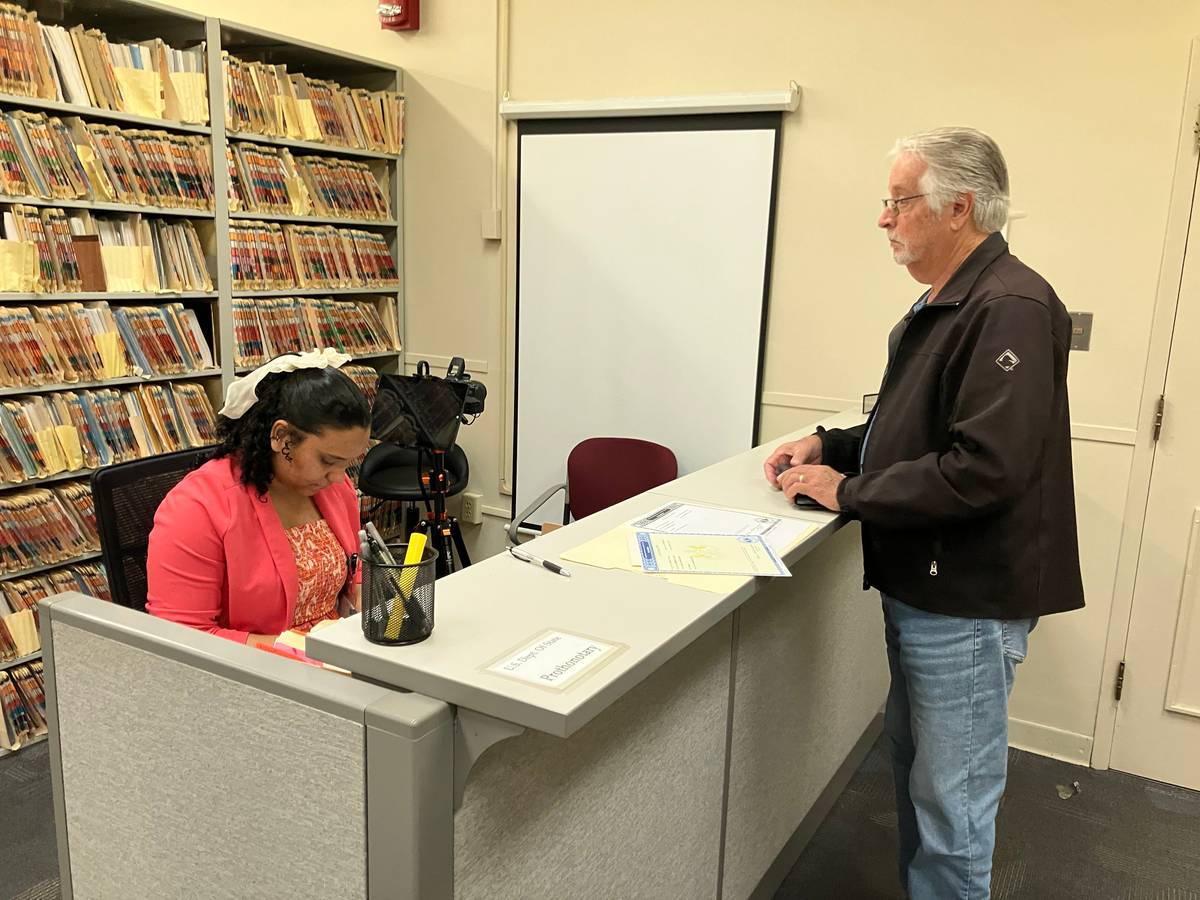

Bouncing in the van with Mike Adams, proprietor along with his wife Ashley of Cocoa Kayak Rentals of Hershey, on the way to put-in at the Swatara Creek for an outing – say, for a certain local editor’s stag party a few years ago – you might be quizzed about the history of the 72-mile-long tributary of the mighty and ancient Susquehanna River.

There are some common pieces of trivia.

Where does the name “Swatara” come from? (Answer: It’s derived from a Susquehannock word for “where we feed on eels.”)

What historic American transportation infrastructure once followed the creek? (Answer: The Union Canal.)

But there are some less common questions – one in particular that you might call an imponderable. The type of question that sparks curiosity and wonder.

The type of question that humbles us humans. We humans, the current and by no means long-lived species that at the moment dominates this pale blue dot of ours.

How old is the Swatara Creek?

How old, indeed.

Deep time – geologic time – warps our sense of context. The great contemporary writer John McPhee put it this way:

Consider the earth’s history as the old measure of the English yard, the distance from the king’s nose to the tip of his outstretched hand. One stroke of a nail file on his middle finger erases human history.

John McPhee, Basin and Range (Annals of the Former World, Book 1)

Imagine then we are starting this little story of ours somewhere around the king’s knuckles, circa 300 million years ago. Deep enough for our purposes, but more or less wading in a kiddy pool when it comes to navigating the eddies of geologic time.

By that time 300 million years ago, the Susquehanna River was already ancient, but how old precisely is a question still out of grasp by human ken. The river channel may have been first formed during the Taconic Orogeny, a mountain-forming event in the early Paleozoic Era, as a drainage into an inland sea that once stretched from western Pennsylvania to Nevada. Perhaps it’s even older than that. Suffice to say for our purposes that the Susquehanna has been evolving over hundreds of millions of years, originating during the Paleozoic Era.

Ted Tesler, a senior geoscientist with the Pennsylvania Geological Survey, approaches questions of this simplistic enormity with the nuance you’d expect from any practiced professional. Black and white worldviews and quick assertions are indulgences lost to those who truly master their fields. How old is the Swattie? You might as well ask how many grains in the Sahara.

Tesler took LebTown under his wing to explain what he knows about the formation of the Swattie, and help unpack our core question: Could the Swattie be just as old as the Susquehanna? Might our stately Swattie have predated the dinosaurs? Did it witness the rise and fall of the mountain range that is today’s grinded-down Appalachians?

The thing about a creek is, it always seems young. At least to this editor. Sure, some might seem more mature for their age – the robust Swattie compared to the sprightly and coy Quittie, the whippersnapper Beck’s, the teenage tortugan Tulpehocken. They are but sprouts compared to the sprawling Susquehanna. Or – are they?

What follows is a reduction – how else to fit hundreds of millions of years of geological history into an 8-minute read? – and Tesler caveats that the geological history of Lebanon County is structurally complex and spans several different major plate collision and crustal expansion events.

He explains to LebTown that the uplift associated with the Alleghenian Orogeny, approximately 300 million years ago, is principally responsible for the Appalachian Mountains and the erosional features that shape the Susquehanna River.

“The Susquehanna is one of the oldest rivers in the world, cutting through rock and sediments even as they were being uplifted during the creation of the Appalachian Mountains,” said Tesler. “It is likely the Swatara Creek has always been a tributary to the Susquehanna based on proximity.”

As our consummate tour guide Adams points out, the ancient mountain ridge to the north of the watershed funneled everything towards the creek, with the natural topography of the south pushing it down until they meet. Spring-fed tributaries add to the drainage until it becomes a major tributary.

Tesler notes that research has suggested the Quittie and Swattie actually began as separate drainages into the Susquehanna until the Swattie captured the Quittie as the surficial drainage system matured in the northern portion of the county.

Signs of the creek’s antediluvian character abound during a paddle, and add to the overall enjoyment of the watershed, not to mention the paramount importance of its preservation.

Around the time the Susquehanna channel may have been first forming, before the Appalachians were created, the land under our feet was on a volcanic arc. Today we can see remnants of this vulcanic activity in the form of a lava deposit field along the creek.

Read More: What exactly is the “Jonestown Volcano”?

“The Jonestown Volcanic Suite (JVS) igneous rocks are likely associated with arc volcanism during the early Paleozoic Era,” said Tesler. “These rocks (principally andesite) were erupted during the Ordovician Period in a shallow marine environment, which is supported by the presence of pillow basalts within the JVS rocks.”

These erupted rocks formed on the flanks of a volcanic arc during the Taconic Orogeny around 440 million years ago, he said.

The later Acadian (370 million years ago) and Alleganian (260-325 million years ago) orogenies resulted in the creation of the Appalachian Mountains.

“These three major mountain building events involved subduction of oceanic crust beneath the eastern continental margin,” said Tesler. “During subduction, the JVS and other early Paleozoic sediments were extensively deformed and transported inland.”

Tesler notes that Pennsylvania’s igneous rocks are not limited to Lebanon County, but lay in a band that extends from Adams and York counties on a east-northeasterly course through to Bucks County. The Jonestown volcanic field is unique for the window it provides into earlier Ordovician-aged volcanic rocks.

One of Swatara Creek’s most impressive features is the “Blue Rock,” a massive limestone outcrop that sits above a deep hole on the Swattie.

The rock, Tesler explains, is Ordovician-aged Hamburg Sequence Limestone.

Ordovician-aged, meaning it was formed in a period around 450 million years ago.

Hamburg Sequence, a specific formation found in Pennsylvania consisting of metamorphosed volcanic and sedimentary rocks with a complex tectonic history, with cleavage formation and thrust sheets of older rocks that have since been left disconnected their contemporaries, surrounded by younger rocks due to erosion.

Sections of the Swattie follow the orientation of these bedding planes and fractures, Tesler notes, citing work by Harold Meisler in the 1960s.

The Blue Rock is both exploited by and exploiting the creek in terms of rock erosion. Rain and surface waters contain dissolved carbon dioxide which can dissolve the calcium carbonate in the limestone. Additionally, dissolution is more likely to occur along flow paths that follow bedding planes, fractures, and variations in porosity, like those surrounding the Blue Rock.

Adams says there are other similar, smaller features along the Swattie, but nothing of the magnificent scale of the Blue Rock.

While the Blue Rock might be your editor’s favorite feature on the creek, you won’t be able to tease an answer out of Adams if you, like many customers, ask about his own favorite.

“It’s such a vast, large watershed that I have to give them the answer everybody hates, which is I like it all,” said Adams.

With its more than 60 navigable miles familiar to him, Adams combination of deep background in nature, ecology, biology, and history, along with countless hours paddling the Swattie, enables him to look past the “rock stars” of the watershed and appreciate the subtle characteristics otherwise missed.

What Adams seems drawn to most is the dynamic nature of the watershed, being able to spot something new and unique on most every outing with his expert eye. He’s able to read the creek as a text, peeling back layers to unpack which changes might have been geological, which anthropological. From the Union Canal’s use of creekside rock for building materials or creating grading for the canal, to hints of dam-like structures going out across the watershed which might have been laid by Native Americans, Adams says you can more or less see the journey through time as you peel away the layers.

“It’s interesting to see how the watershed was used throughout recorded and unrecorded history, because it’s always been a source of more or less abundance, so obviously mankind as a species has kind of taken advantage of that abundance,” said Adams.

Read More: A decades-long project almost dammed the Swatara Creek and radically altered northern Lebanon County

Adams said he thinks understanding the geologic and human history for the creek enhances one’s overall appreciation and experiences out on the creek.

“If you can give them a small base of knowledge, it kind of opens up their experience, which adds value,” said Adams.

As a Penn State Extension master watershed steward and vice president of the Swatara Watershed Association, Adams said that through those organizations and others, like the Manada Conservancy, there are constant efforts on preserving the creek and educating the public on the benefits of preserving and rehabilitating the watershed for future generations.

Swatara Watershed Association president Bethany Canner echoes Adams.

“You could study it for your whole life and still just scratch the surface,” said Canner.

Every stream, creek, or river is its own complex ecosystem and, for the Swattie, its own community, too. A creek, Canner points out, is human-scale; approachable in a way the Susquehanna is not, even if they might be similarly old beyond our comprehension. And we have its geology to thank for its gentle stream, perfect for a summer paddle and the chance to observe the different formations – at least the ones above the waterline. (The activity below the surface is another topic of interest; Canner notes there’s a ton of amazing underwater geology such as big shelves and deep trenches, especially towards the southern end of the creek.)

Read More: Travel down the Swatara Creek without getting wet with SWA’s 360° virtual tour

“The geology is the thing we can’t change, and it’s the basis everything is built on as far as the creek goes,” said Canner. “We can’t change the bedrock that the creek is flowing over, so that’s kind of our starting point and we have to go from there to take care of the creek.”

Questions about this story? Suggestions for a future LebTown article? Reach our newsroom using this contact form and we’ll do our best to get back to you.

Be part of Lebanon County’s story.

Cancel anytime.

Monthly Subscription

🌟 Annual Subscription

- Still no paywall!

- Fewer ads

- Exclusive events and emails

- All monthly benefits

- Most popular option

- Make a bigger impact

Already a member? Log in here to hide these messages

Strong communities need someone keeping an eye on local institutions. LebTown holds leaders accountable, reports on decisions affecting your taxes and schools, and ensures transparency at every level. Support this work with a monthly or annual membership, or make a one-time contribution. Cancel anytime.