There comes a time each year when snowbirds fly south to Florida. This is the story of one man, Robert H. Coleman, who made the journey.

Part 1 of this series on the curious life and legacy of Robert H. Coleman examined the circumstances that lured him to risk his vast fortune in Florida.

Part 2 looked at Robert H. Coleman’s upbringing and education, and the early passions that came to play a huge role in his life and career.

Part 3 explored the full scope of all Coleman’s activities in Lebanon County during his “busy decade.”

Part 4 looked at how Coleman’s Florida exploits led to his undoing.

Part 5 covered how Coleman found sanctuary in Saranac Lake.

In this installment, learn about an unfortunate case of more grief for Coleman endured late in life.

Robert H. Coleman, once the beloved “Iron King” of Cornwall and Lebanon in the 1880s, spent the second half of his life in relative solitude in Saranac Lake, New York. After the death of his mother in 1892, then suffering financial ruin in 1893, trouble continued to follow him.

In 1903, Edith his second wife had died of tuberculosis. Robert’s first wife Lillie had died in the first year of their marriage 23 years before. He was alone again, at 47 years of age, and suffering his own ill-health.

Although it had been said Coleman never again left Saranac Lake, in August of 1910 he did in fact have to travel to Buffalo, New York, to identify the remains of his youngest son Ralph.

Ralph had voluntarily withdrawn from Yale class of 1912 earlier in the year. His diary hinted at trouble with the college faculty. Having “no hope,” he had left to take up work in western New York, only to commit suicide.

Then imagine Robert’s grief to receive news in October 1918 of the death of his oldest son, Robert. His three boys were serving in serving in Europe in the “great war.”

It is unclear how quickly the report of his death on October 9 reached Robert, but the news must have been devastating. Possibly he felt some consolation that his son died of pneumonia rather than suffering violence as a casualty of war. Soon after he wrote to his friend Judge Henry in Lebanon (Charles V. Henry of Annville, appointed June 2, 1910, to the 51st judicial district upon the death of his predecessor).

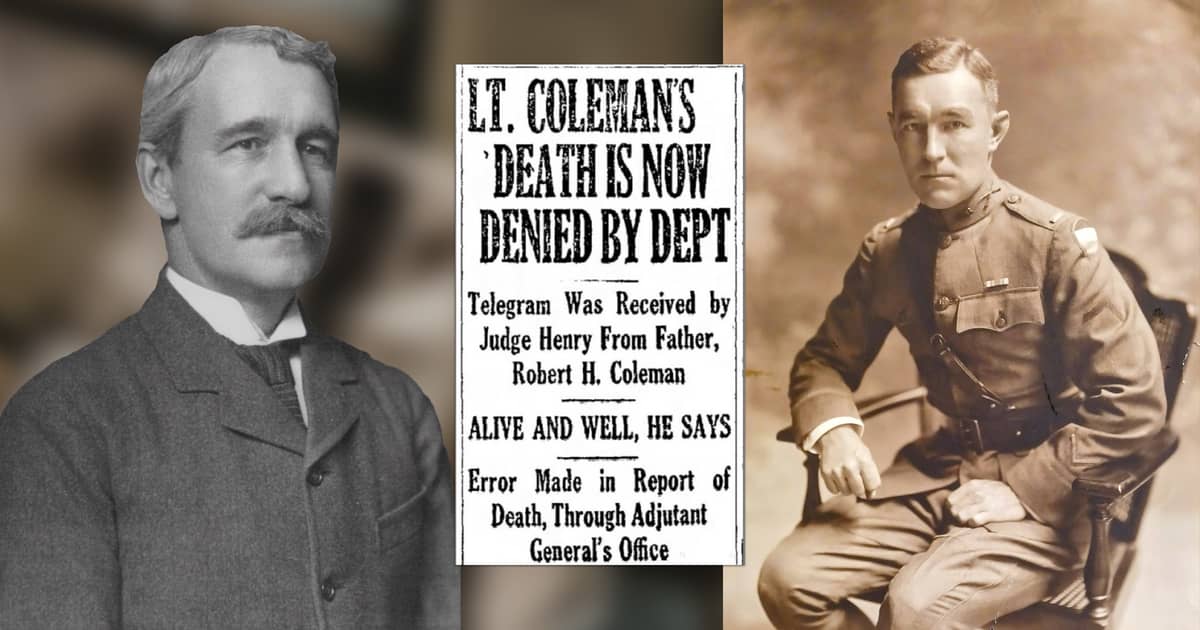

Judge Henry subsequently shared the sad news, which appeared in Lebanon’s “The Daily News” almost a month after the fact on November 6th.

But then, imagine the confusion and immense relief that Robert H. Coleman felt in mid-November when the War Department followed up with a correction; young Lieutenant Coleman was alive after all. A telegram from Saranac Lake to his friend Judge Henry carried the good news, and the follow-up story appeared (below) in The Daily News on November 14, eight days after the first misleading report.

Perhaps the error on the part of the War Department was excusable. In 1918 the world was experiencing a pandemic of Spanish flu. While World War I claimed 53,402 combat deaths, an additional 45,000 American soldiers died of influenza and related pneumonia that year. At home, 675,000 Americans died, twice the death rate per capita of American’s dying from COVID-19 in this century. Hearing of his son’s death might have struck him in the same way as some of us who had lost a family member to COVID.

Read More: 100 years ago, Lebanon grappled with a very different pandemic—the Spanish flu

The following year young Robert, very much alive, wrote his father from Clemency, France, a long typewritten letter dated February 24, 1919. He shared how he had been leading a group of “Arkansas hill-billies” and told of servicemen in France living it up with wild women and wine, but that he was being careful and saving his money. He dreamt of using some of it to buy an airplane when he finally got home, as he had experienced some flying.

Then he mentioned that there are things the American public “should know, but don’t” about the soldiers’ welfare. He was “sick of the Army game” and looked forward to coming home for good in July. In one revealing comment: “I have not allowed you to pull any strings since I have been in the Army but the chances are that I will need a few gentle pulls when I get out.”

Robert Coleman, the younger, survived his father who died in 1930, and lived a full live until his death in 1964.

On Tuesday evening, August 13, the Cornwall Iron Furnace will kick off its 2025 season of lectures with a presentation by the author “Memories that Linger – the Unpublished Story of Robert H. Coleman.” Click this link for more information and to sign up for access to the Zoom meeting. Alternatively you may attend in person at Cornwall Manor Freeman Auditorium.

Story Credits

Eric Durr, from his New York National Guard report on Spanish Flu in WWI (August 31, 2018).

Jim Polczynski (author of “Souls of Iron”) for locating the ‘correction’ story by The Daily News.

Read Part 4 of Robert H. Coleman, Florida Man, here.

Read Part 4 of Robert H. Coleman, Florida Man, here.

Read Part 3 of Robert H. Coleman, Florida Man, here.

Read Part 2 of Robert H. Coleman, Florida Man, here.

Read Part 1 of Robert H. Coleman, Florida Man, here.

Questions about this story? Suggestions for a future LebTown article? Reach our newsroom using this contact form and we’ll do our best to get back to you.

Be part of Lebanon County’s story.

Cancel anytime.

Monthly Subscription

🌟 Annual Subscription

- Still no paywall!

- Fewer ads

- Exclusive events and emails

- All monthly benefits

- Most popular option

- Make a bigger impact

Already a member? Log in here to hide these messages

Local news is a public good—like roads, parks, or schools, it benefits everyone. LebTown keeps Lebanon County informed, connected, and ready to participate. Support this community resource with a monthly or annual membership, or make a one-time contribution. Cancel anytime.