A Lebanon Valley College professor has completed a study of prison recidivism that has revealed some interesting results about crime and punishment in Belize.

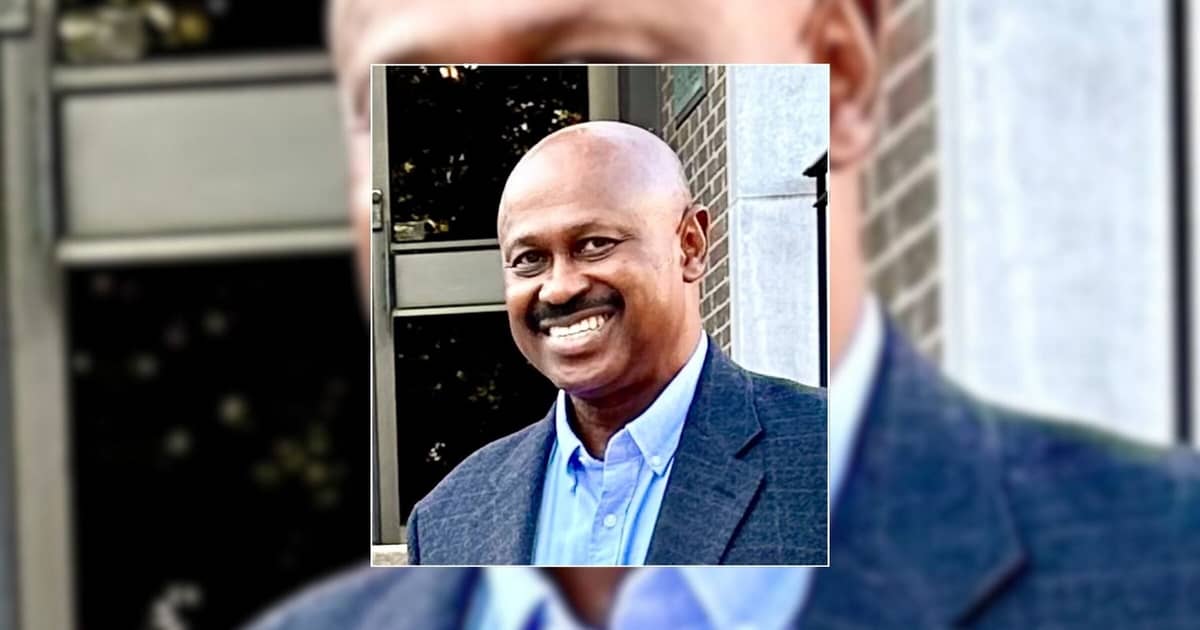

Dr. Terrence A. Alladin, associate professor of criminal justice at LVC, conducted a prison recidivism study in Belize over the 2024-25 academic year through a Fulbright U.S. Scholar award.

During that study he learned there are stark contrasts between recidivism there and in the U.S.

“What we found in Belize is that Belize has a significantly lower recidivism rate than the United States in that their recidivism rate was around approximately 24 percent,” Alladin said. “Depending on state and federal prison, it’s about 40-plus percent. If you average the states, the states are about 50 to 60 percent, so it varies.”

Alladin said he spent about 1.5 years in-country and studied data from 2019 through 2024 of Belize residents who had served time at Belize Central Prison, the nation’s one jail.

The research, conducted in collaboration with Galen University, focused on the use of peacemaking criminology as a nonviolent approach to criminality.

Peacemaking is a theory developed by Richard Quinney and Harold Pepinski that suggests that alternative methods can be used to create peaceful solutions to crime while also reducing violence.

There were more differences than just the prison recidivism percentages in the U.S. and Belize.

“What I found is that they have a really, what I would say is, robust community support,” Alladin said. “They have their rehabilitation programs that are much more geared towards helping a person when they’re incarcerated and providing a path for them when they get out.”

That is telling given that Belize is a much poorer nation than the U.S. Alladin added that the treatment programs offered to violent offenders leads to lower return rates than in this country.

Read More: LVC professor selected for Fulbright Scholar award for research in Belize

“Even though they have less resources than we do in the United States, those resources are used a lot more efficiently,” he said, adding that money isn’t the solution to the problem.

“Resources are scarce and they have found ways of reducing recidivism without spending the kinds of money we spend,” the professor added. “We spend $134 per inmate per day in the U.S. They spend a little more than 20 in U.S. dollars per day, and their results are a lot different.”

It costs just under $131 a day to house an inmate at LCCF, according to prison warden Tina Litz. She saidthat the county does not have figures concerning recidivism.

Another contributing factor is the distinct cultural differences between Belize and the U.S.

“There is also a stigma that the country still has, that the community still has, or I should say the society in Belize still has. They see being incarcerated as a kind of a stigma to a person, and so people really don’t want to be incarcerated,” Alladin said. “While in the United States, and again depending on some communities, being incarcerated is like a badge of honor. So there is that difference in values and culture.”

The concept of crimpenury

LebTown asked Alladin if he studied the nature of the crimes that were committed by Belizeans.

“What I found is that most of the crimes in Belize are what I call nonviolent crimes. What I mean by nonviolent crimes, Belize has what I call some unique statutes or laws on the books that, for instance, people were incarcerated for not wearing a mask during COVID. And because they couldn’t pay those fines, they end up being incarcerated,” Alladin said.

He believes it is wrong to jail individuals who commit non-violent crimes simply for an inability to pay fine costs.

“Some of those crimes, some of those numbers really upped the number of people who were incarcerated. If I should take those, what I call, non-crimes, again, in my words, crimes in that I don’t feel it’s right to incarcerate a person because they didn’t wear their mask or couldn’t or they can’t afford to pay the fines,” he said.

Other non-violent crimes also lead to prison time, especially given the high rate of poverty in Belize.

“What they’re doing is using crime and poverty to incarcerate people who shouldn’t be incarcerated,” noted Alladin. “If you’re riding a bicycle on a one-way street, if you’re riding in the wrong direction, you can be arrested. And if you don’t, I mean, you can be fined. If you’re not able to afford to pay that fine, then you’re incarcerated for a month, two months, depending upon the judge.”

The relationship between committing an offense that carries a fine that an offender is unable to pay has led Alladin to coin a new word that he also has copyrighted.

“Crimpenury” is a phrase I coined to describe the intersection of criminalization and poverty,” Alladin said, “(and it) has been officially copyrighted and added to the criminal justice lexicon.”

Alladin said crimpenury has five characteristics.

- Criminalization of Poverty-Related Behaviors: Laws and policies that penalize survival strategies associated with poverty, such as loitering, homelessness, or petty theft. These often result in disproportionately high rates of criminalization for those living in poverty.

- Poverty as a Driver of Crime: Economic deprivation can push individuals toward criminal activity as a means of survival, leading to higher rates of theft, drug trafficking, or other forms of illicit income generation among impoverished populations.

- Barriers to Reintegration: Individuals who come into contact with the criminal justice system, especially those from poor communities, face systemic obstacles when trying to reintegrate into society. Criminal records limit access to employment, housing, and education, creating a vicious cycle of poverty and recidivism.

- Disproportionate Policing in Poor Communities: Law enforcement practices often concentrate in low-income areas, leading to over-policing and higher incarceration rate among poor populations. This further exacerbates economic disparities, as individuals lose jobs or income due to arrests and imprisonment.

- Poverty as a Consequence of Criminalization: Many laws targeting low-level offenses, fines, or fees disproportionately affect the poor, trapping them in cycles of debt and legal trouble. Those unable to pay fines or secure legal defense are often subject to harsher penalties, deepening their economic struggles.

Crimpenury examples

Alladin noted that in Belize anti-homelessness ordinances that criminalize sleeping in public spaces, lead to arrests and fines that homeless individuals cannot afford to pay. Additionally, he said that “bail systems that disproportionately affect poor defendants, keep them incarcerated simply because they cannot afford bail, even for minor offenses.”

“Fines and fees for low-level offenses that result in escalating legal consequences for those unable to pay, pushing individuals deeper into poverty and the criminal justice system,” he stated. “In essence, crimpenury underscores how the convergence of poverty and criminalization perpetuates social and economic inequalities, much like “crimmigration” highlights the fusion of immigration law and criminal justice.”

Post-study next steps

Alladin is waiting to learn the date in May when his research will be published in the “Journal of Belizean Research.” He said he was unable to provide exact details about recommended actions since he has an agreement to first publish that information in the journal. He was, however, able to share his plans post-publication.

“The Belizean government is planning to meet with me to see what steps, after it’s published, what steps can they take to improve their criminal justice, their correction systems, and they will be willing to have a discussion,” he said. “I think from there we can decide to go nationwide. I know Trinidad and Guyana, which is in the West Indies, are also waiting on the results to see if there’s things that they can do to improve their systems. So I think there’s a lot of promise. It’s just that we have to wait until it comes out and people get to read and decide what they want to do.”

Alladin said he will speak at conferences in America and work with states looking to lower their recidivism rates, including here in Pennsylvania. He also plans to work with officials to find ways to learn why crime happens, hoping to address it at the source as a way to reduce it. He used an analogy to make his point.

“If you go home today and you see water running out your door, do you grab a mop and start mopping up the water? Or do you go looking for the source of the water and turn it off and take care of that, then grab a mop?” Alladin said. “How we tend to fight crime, we start grabbing mops and then say, ‘Okay, we need more mops, we need more mops, we need more mops, we need more people with mops.’ That’s not the way. We need to look at the source of why kids, why adults commit crimes.”

Ultimately, Alladin said Americans need to change the way they view crime.

“First of all, we have to change our way of thinking for every punishment, for every issue that comes along, for every incident, we feel that incarceration is the best tool. That begins on the government level,” Alladin said. “Then we also have to educate our kids, let them know incarceration is not the way to go. Being incarcerated is not a badge of honor. So it requires changes on both sides.”

Alladin is a tenured professor at LVC. After teaching asynchronously last year while working on his Fulbright Scholarship research, an experience he described as “rewarding but tiring,” he said his focus this semester has been on building out the college’s Criminal Justice department.

Alladin’s spring semester courses had been reassigned following an email exchange between Alladin and students about volunteer opportunities for the criminal justice program. In the emails, Alladin said that as a former Trooper, he knew “unsavory people” he could “send to your door” and that he was sure they could “guarantee your participation.” Alladin said in a followup email to students that he had been writing in jest, but that he took full responsibility for his words and any impact they had. “In trying to make a joke about threats, I realize that my words may have caused discomfort or concern,” said Alladin in the email. “That was never my intention, and I sincerely regret that my email may have been perceived as anything other than an attempt at humor.” Alladin and LVC declined to comment further, citing college policy against commenting on personnel matters.

“I’m also enjoying some well-deserved time with my family and am looking forward to ushering in a new cohort of criminal justice students in the Fall (semester),” he said.

According to LVC’s course catalog, Alladin will be back in the classroom this fall leading courses such as Intro to Criminal Justice, Legal Procedure: Accused Rights, and Wrongful Conviction.

Editor’s note: This article was updated after publication to include more information on Alladin’s spring semester courses.

Questions about this story? Suggestions for a future LebTown article? Reach our newsroom using this contact form and we’ll do our best to get back to you.

Keep local news strong.

Cancel anytime.

Monthly Subscription

🌟 Annual Subscription

- Still no paywall!

- Fewer ads

- Exclusive events and emails

- All monthly benefits

- Most popular option

- Make a bigger impact

Already a member? Log in here to hide these messages

Local news is a public good—like roads, parks, or schools, it benefits everyone. LebTown keeps Lebanon County informed, connected, and ready to participate. Support this community resource with a monthly or annual membership, or make a one-time contribution. Cancel anytime.