Cornwall Borough resident Bruce Chadbourne offers another of his “Who Knew?” installments of Lebanon Valley history. The extended Coleman family, iron masters of Elizabeth, Cornwall, and Lebanon furnaces, has been known in various ways for its kindness and generosity to the many local charities, including numerous churches, hospitals and even women’s shelters. Here is another surprising story from the family archives of George Dawson Coleman.

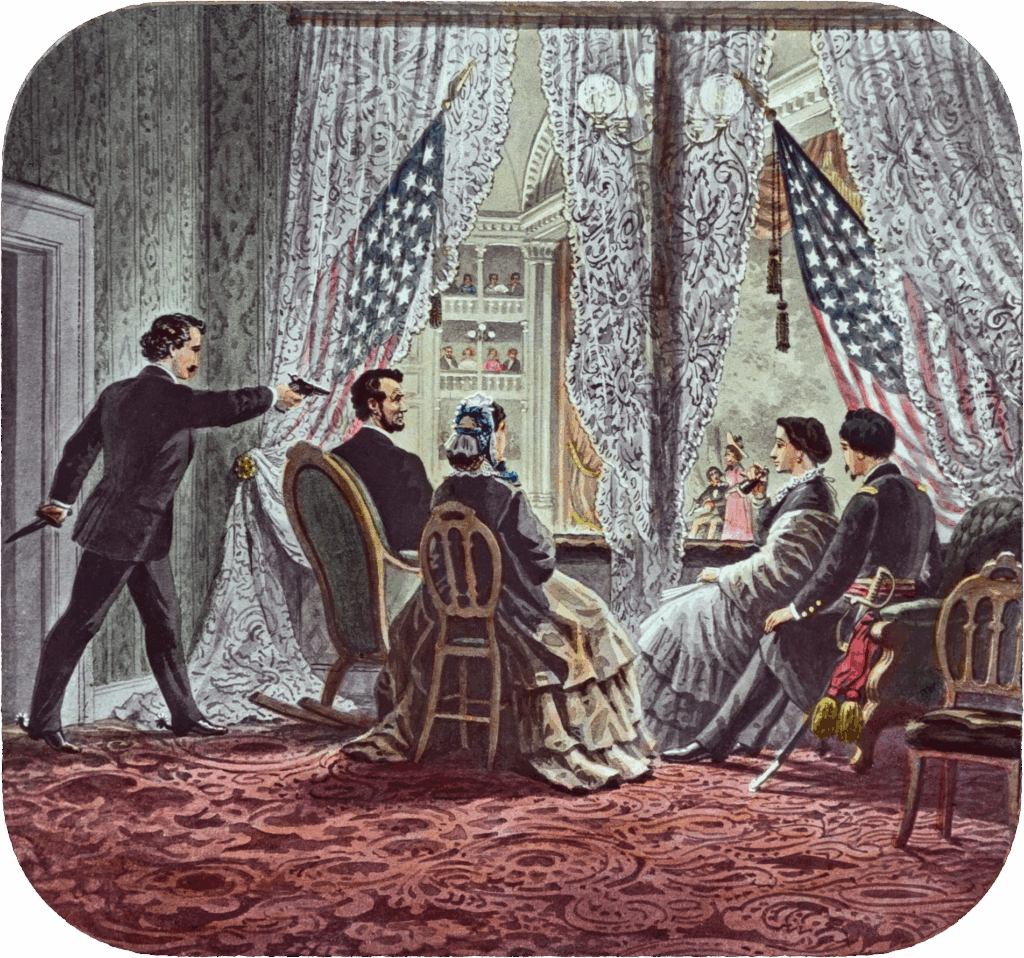

Mentioning the Lincoln assassination evokes for most people images of John Wilkes Booth sneaking into the presidential box of Ford’s Theater, and upon firing the fatal shot, leaping to the stage floor with shouts of “Sic semper tyrannis!”

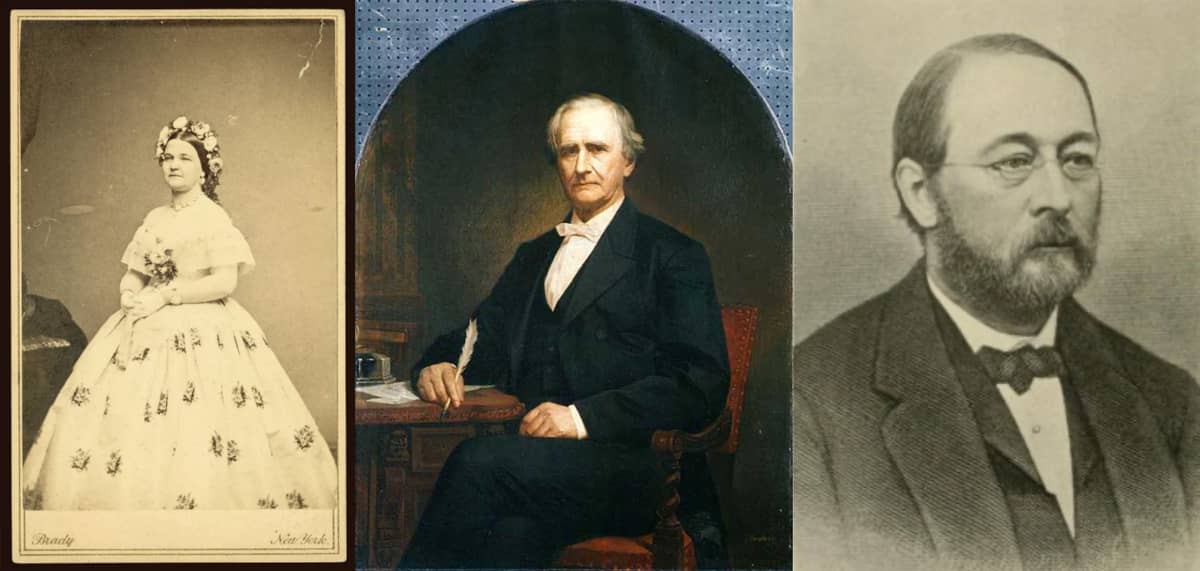

Years later, speaking at the funeral of Mary Todd Lincoln, a clergyman remarked that a single bullet claimed two victims.

Mary’s life quickly changed after the assassination in April 1865. In the ensuing months this First Lady was essentially homeless, starting over in Chicago. The Lincolns had previously lost two of their sons Eddie and Willie. She and two remaining sons, Robert and Tad, stayed at the Tremont Hotel.

Much of what is written about Mary Todd Lincoln is critical. She had drawn much public criticism during their White House years for her obsession with expensive furnishings. The excesses caused the President to bear personal debt of almost $10,000 ($250,000 in today’s value) against his annual salary of $25,000. On his death the debt became her responsibility.

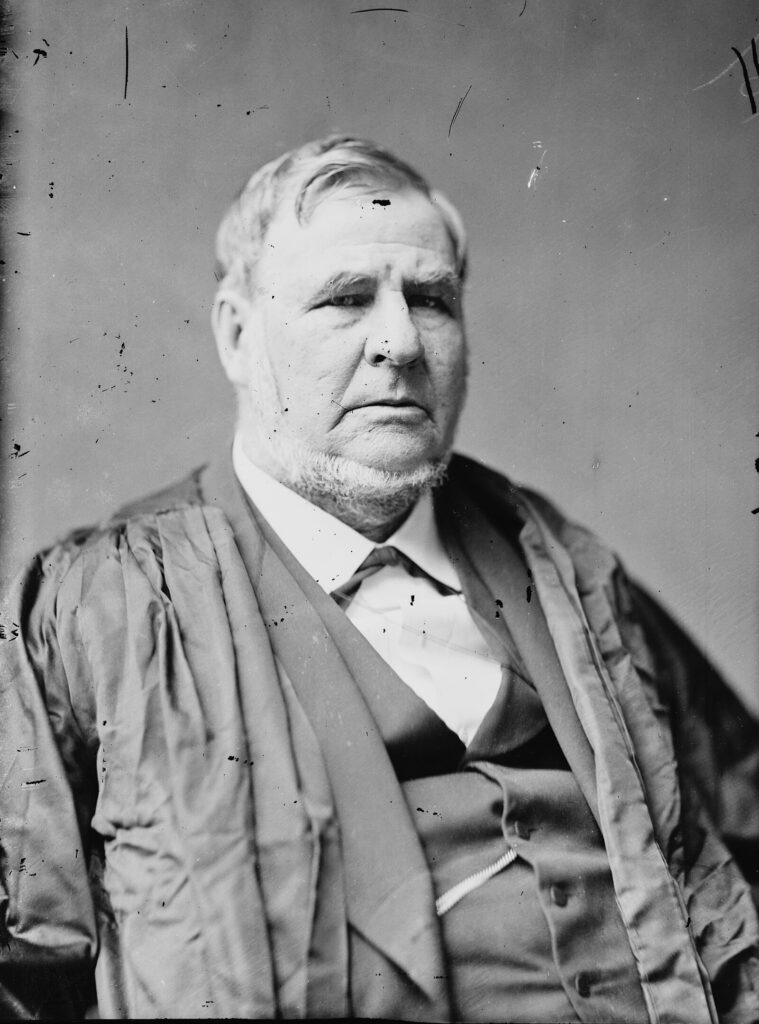

Lincoln’s estate was worth about $80,000 and, as he died without a will, the estate was administered by Supreme Court Justice Judge Davis, who encouraged Mary to return to the Lincoln home in Springfield, Illinois. But she refused to live in a place where she would be constantly reminded of the loss of her husband. She wore Victorian mourning garb for the rest of her life.

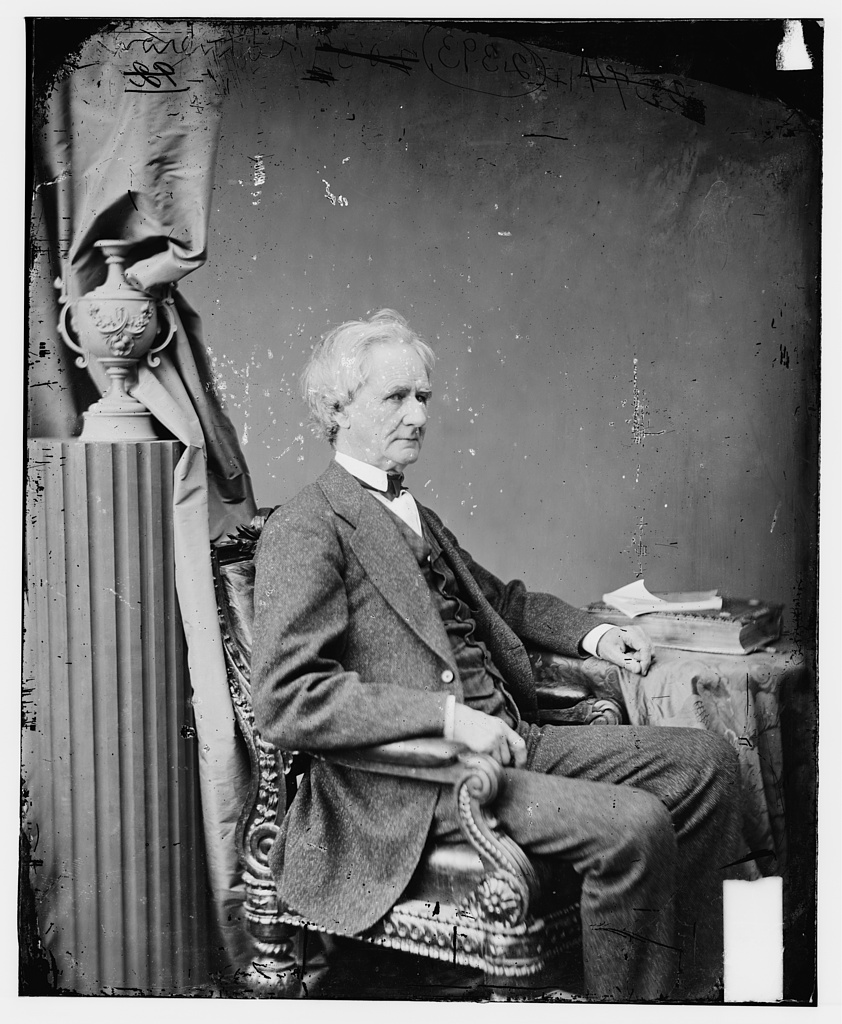

Simon Cameron (1799-1889)

Pennsylvanians have many reasons to know of General Simon Cameron, a Pennsylvania politician who was Lincoln’s secretary of war for several years before resigning in 1862 under the cloud of scandal concerning supply contracts. He had been nominated for the presidency in 1860, subsequently throwing his support to Lincoln, earning him the cabinet position.

He had come from Maytown, west of Lancaster and rose to fame working in Harrisburg newspapers, where he developed many political contacts and passions. In 1829 Pennsylvania Governor Shulze named him state Adjutant-General, for which he preferred to retain the title “General” for the rest of his career.

He had been United States Senator on two occasions, in 1845 and 1857, to be elected yet a third time in 1866. His reputation continued for decades after for the political machine he built, wielding power over state jobs and contracts, a machine that continued under his son Daniel Cameron (who had served as President Ulysses S. Grant’s secretary of war).

Cameron had purchased the Harris House in Harrisburg in 1861, and the house continues to stand in his memory. It is situated prominently on Harrisburg’s riverfront, a few blocks from the State Capitol, and houses the Dauphin County Historical Society.

Mary seeks Cameron’s assistance

Simon Cameron was aware of the difficulties Mary Todd Lincoln was having with Judge Davis managing the affairs of the Lincoln estate. In Chicago she had found rented quarters in a boarding house; such frugal circumstances were unsatisfactory to her style of living.

In a letter to “General” Cameron she complained that Judge Davis was unfairly cold and unsympathetic to her plight and instead should be grateful for the position given him by her late husband. She found “life a torture” in a Chicago boarding house with her sons, “most revolting.”

He had written suggesting that he could solicit funds from sympathetic friends to raise $20,000 so that she could buy a house.

She cautioned him that “plain two-story frame houses” in that neighborhood are lucky to be found at that price, more likely $25,000 to $30,000, but they proceeded with that plan.

In 1866 while Cameron began soliciting his friends, she used some of Lincoln’s final salary to purchase a house for $17,000. An opportunity had availed itself, requiring her to take timely advantage.

She had not adjusted her expectations to a lower standard of living however. Within a year, unable to afford living in her new home, Mary Todd Lincoln rented out the house and moved into Chicago’s Clifton House (above) and would move to various quarters in the years after.

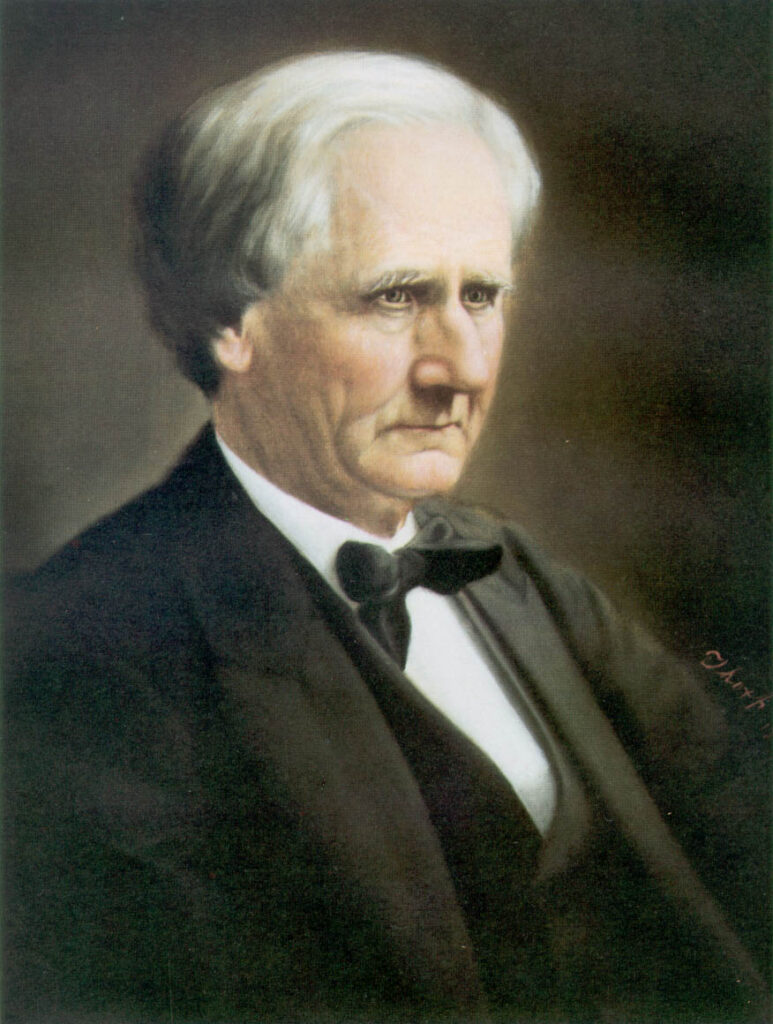

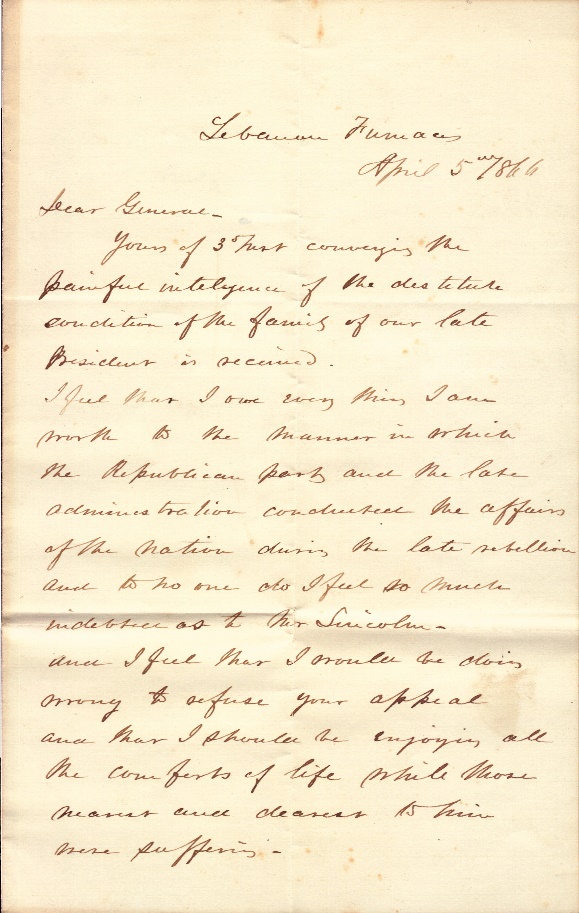

George Dawson Coleman responds

Cameron contacted friends among his many political connections explaining the plight of the wife and children of the nation’s beloved president.

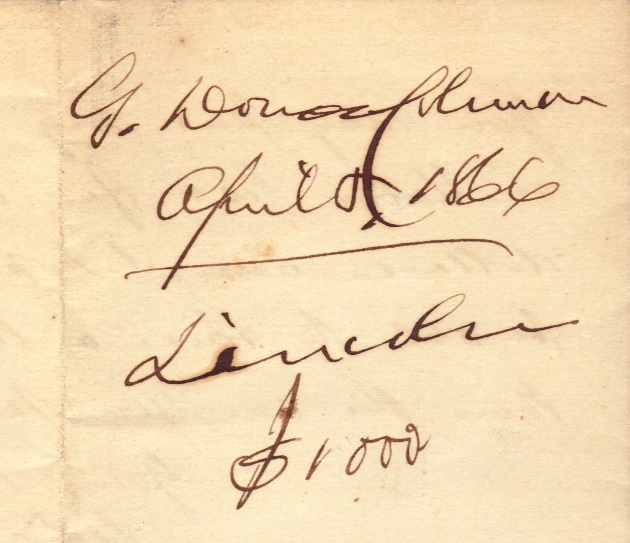

Though most declined to lend assistance, a few friends rose to the occasion; one who stepped up was George Dawson Coleman. His letter below concludes with wishes that more would be raised than “the amount mentioned.”

Lebanon Furnaces, April 5, 1866

Dear General,

Yours of 3 Mar conveying the painful intelligence of the destitute condition of the family of our late President is received.

I feel that I owe every thing I am worth to the manner in which the Republican party and the late administration conducted the affairs of the nation during the late rebellion and to no one do I feel so much indebtedness as to Mr. Lincoln.

And I feel that I would be doing wrong to refuse your appeal and that I should be enjoying all the comforts of life while those nearest and dearest to him were suffering.

You may put my name down on your list for one thousand dollars, and I hope you will be able to raise a larger sum than the one you mention.

Yours truly, G. Dawson Coleman

Coleman’s gratitude

Coleman appreciated Lincoln’s administration for personal reasons as well as how the “affairs of the nation” had been conducted.

A letter from Abraham Lincoln was found in the Coleman mansion during its demolition in 1961. The letter appointed Coleman as commissioner, representing the United States at Great Britain’s 1862 Exposition of the Industry of All Nations. The exposition followed on the heels of Prince Albert’s original Great Exposition of 1851 and was planned to surpass the 1855 Paris Exposition.

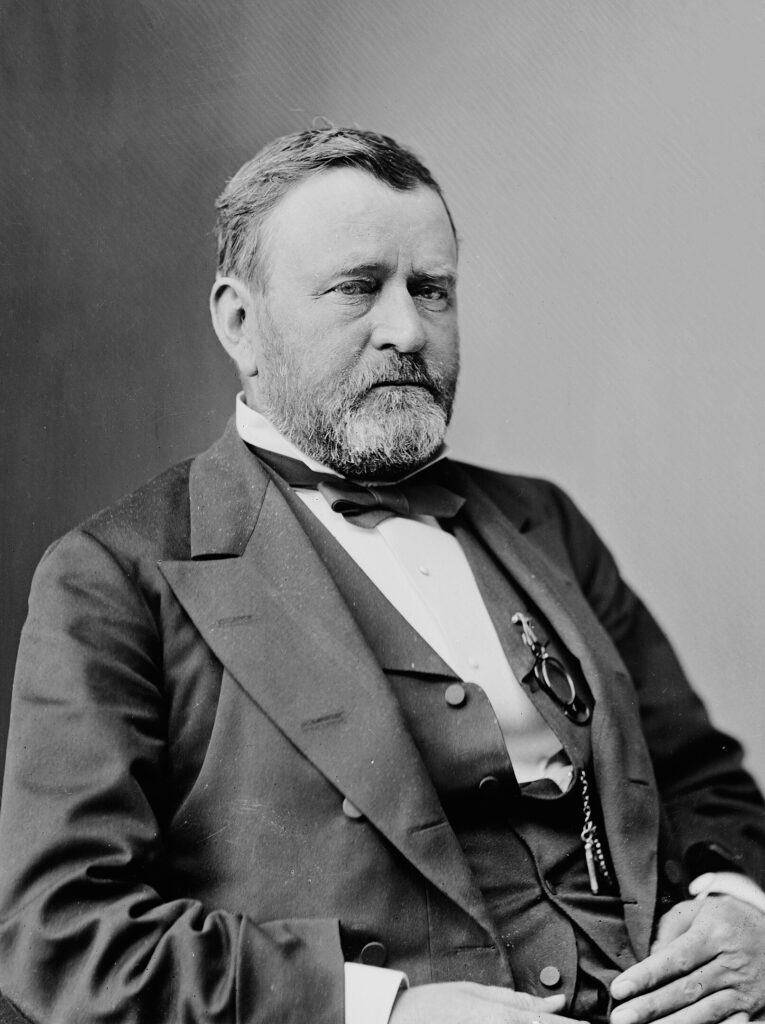

Coleman would again represent the United States in 1873 at the Vienna World’s Fair, appointed by his friend Ulysses S. Grant.

Coleman and Cameron

Coleman and Cameron remained long-time friends. Most correspondence between them was of a social nature. Simon expressed condolences to Deborah Brown Coleman upon her husband George’s passing in 1878. He remained a family friend for another decade until his own death in 1889, including helping to sponsor son Bertram Dawson Coleman on a world-wide trip, providing letters of introduction on his behalf to several foreign ministers.

One letter in 1861 between George and brother Robert Coleman (then in France) discussed the possibility of acquiring Cameron’s influence in selling more iron to the government for the war, however there is no “smoking gun” indicating involvement in a Cameron scandal.

Mary Todd Lincoln’s final years

Simon Cameron’s intentions to help in 1866 were never fully realized. Some responded, but others offered only regrets. He never raised the full amount. Some criticism suggested he was more focused that year on winning his return to the U. S. Senate, and that this seeming act of benevolence was more a matter of gilding his own reputation among supporters.

Later, with Cameron now in the Senate, and thanks to Mary’s own lobbying, Congress finally granted the former First Lady a pension of $3,000 a year, in 1870.

Her final years remained turbulent up to her death at age 63 in 1882. Tad had died in 1871 of tuberculosis. She had lived estranged from her only remaining son Robert, who for a period of time had her committed to an asylum.

There is quite an interesting online history of Mary’s final years, including surviving the great 1871 Chicago fire just two blocks from Mrs. O’Leary’s house.

Carl Sandburg wrote a series of acclaimed biographies of Abraham Lincoln, one winning him a Pulitzer Prize for History. In writing her biography, “Mary Lincoln, Wife and Widow,” Sandburg established how Judge Davis had properly filed statements valuing Lincoln’s estate at $110,000. Though it would not compare to George Dawson Coleman’s millions, such an estate worth $2 million today should have provided for her comfortably.

Unconsolable, she is seen in history crying “poor me!”, a starving, destitute and downtrodden woman. Parts of her life were indeed tragic, but possibly Coleman’s kindness and benevolence had been misplaced.

Story Credits

Craig Coleman, original documents.

Letters in Chicago historian Philip D. Sang’s “Mary Todd Lincoln: A Tragic Portrait,” 1961, Rutgers University Library.

Questions about this story? Suggestions for a future LebTown article? Reach our newsroom using this contact form and we’ll do our best to get back to you.

Keep local news strong.

Cancel anytime.

Monthly Subscription

🌟 Annual Subscription

- Still no paywall!

- Fewer ads

- Exclusive events and emails

- All monthly benefits

- Most popular option

- Make a bigger impact

Already a member? Log in here to hide these messages

Local news is disappearing across America, but not in Lebanon County. Help keep it that way by supporting LebTown’s independent reporting. Your monthly or annual membership directly funds the coverage you value, or make a one-time contribution to power our newsroom. Cancel anytime.