Before Claude Osteen enjoyed his greatest day as a major league pitcher, he endured his share of sleepless nights. Nights when he cursed the fates and questioned the baseball gods. Nights when he fretted about runs that went unscored in support of him and plays that went unmade behind him.

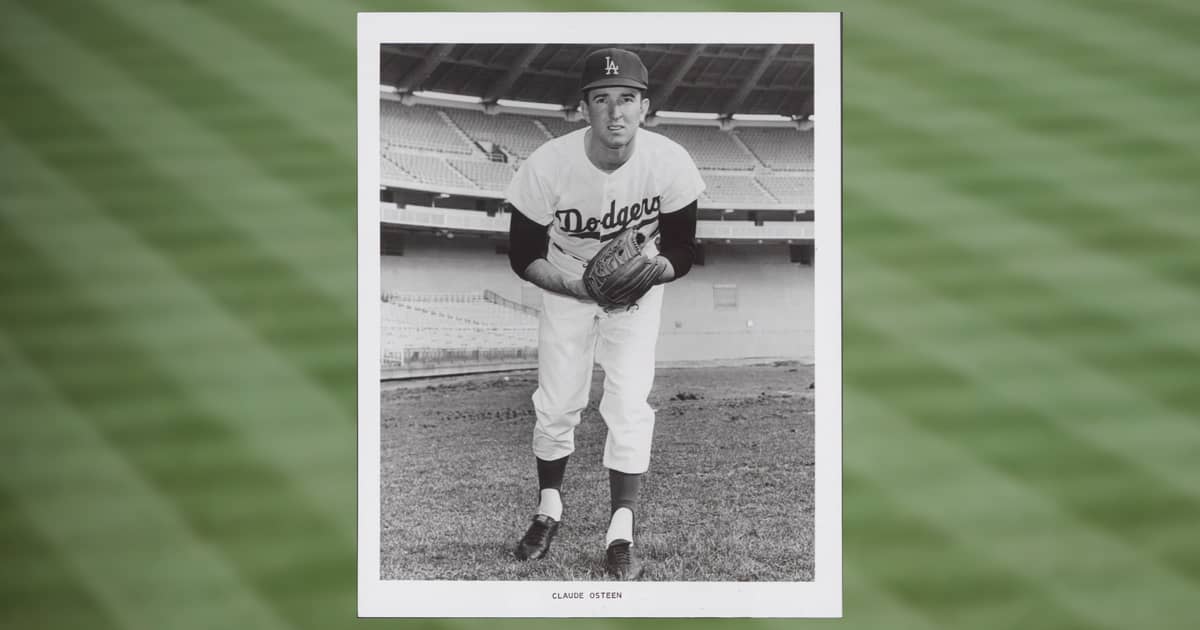

At age 86 he can easily turn back the clock to that time, 60 years ago, when he was in the first of his nine seasons with the Los Angeles Dodgers and the eighth of his 18 in the bigs. That was well before he and his family settled (at least for a time) on a 105-acre poultry farm between Annville and Palmyra, well before he ushered three Phillies to Cy Young Awards as the team’s pitching coach, and well before two of his sons embarked on pitching careers that topped out at the highest rung of the minor leagues.

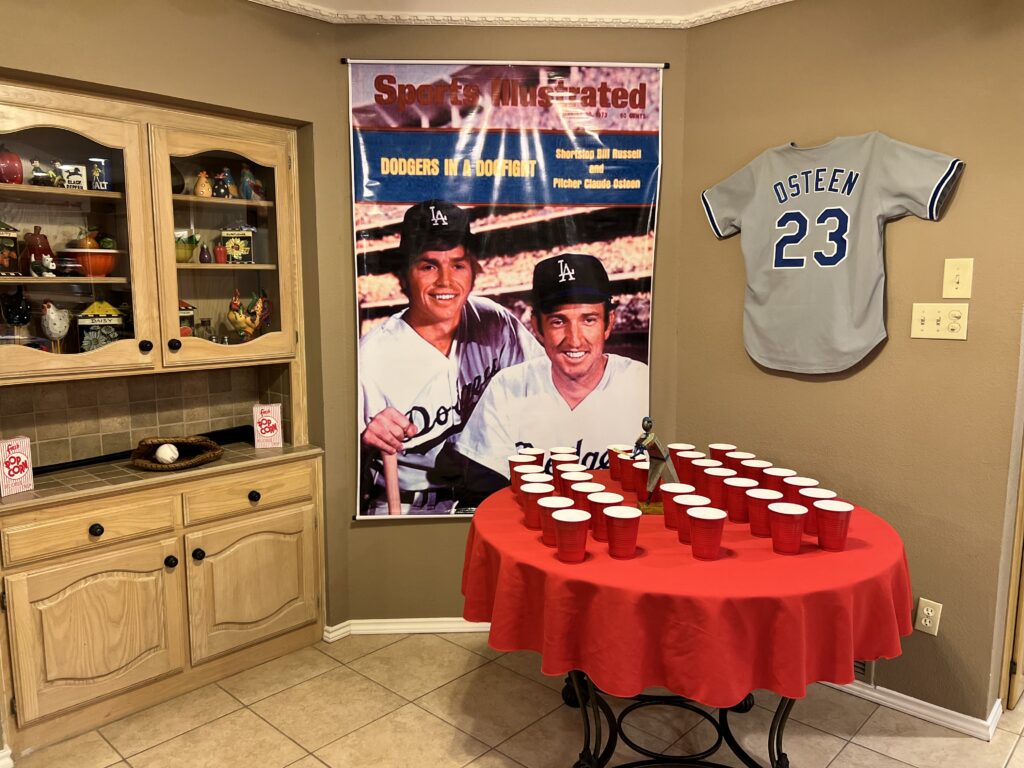

Osteen has long since moved to the Dallas/Fort Worth metroplex, just a stone’s throw from the stadiums that house the Cowboys and the Texas Rangers. But in his mind’s eye he is still the 26-year-old lefty saving the Dodgers’ bacon in the 1965 World Series.

Before that, though, he had to “make a pact with (himself),” as he put it in a recent phone interview. He did it late one night in the middle of that ’65 season, a season in which he fashioned a stellar 2.79 ERA but went 15-15, in large part because the Dodgers scored just 29 runs in his 15 defeats.

“I would go home,” he said, “and replay the game after all my family would go to bed.”

He came to realize that too often he was marinating in the negative – “negatives that I had no control over,” he said. He vowed to put all that aside, best he could, and accentuate the positive. Never again would he let lackluster run support or faulty fielding distract him or sidetrack him. He would live in the moment, pitch in the moment.

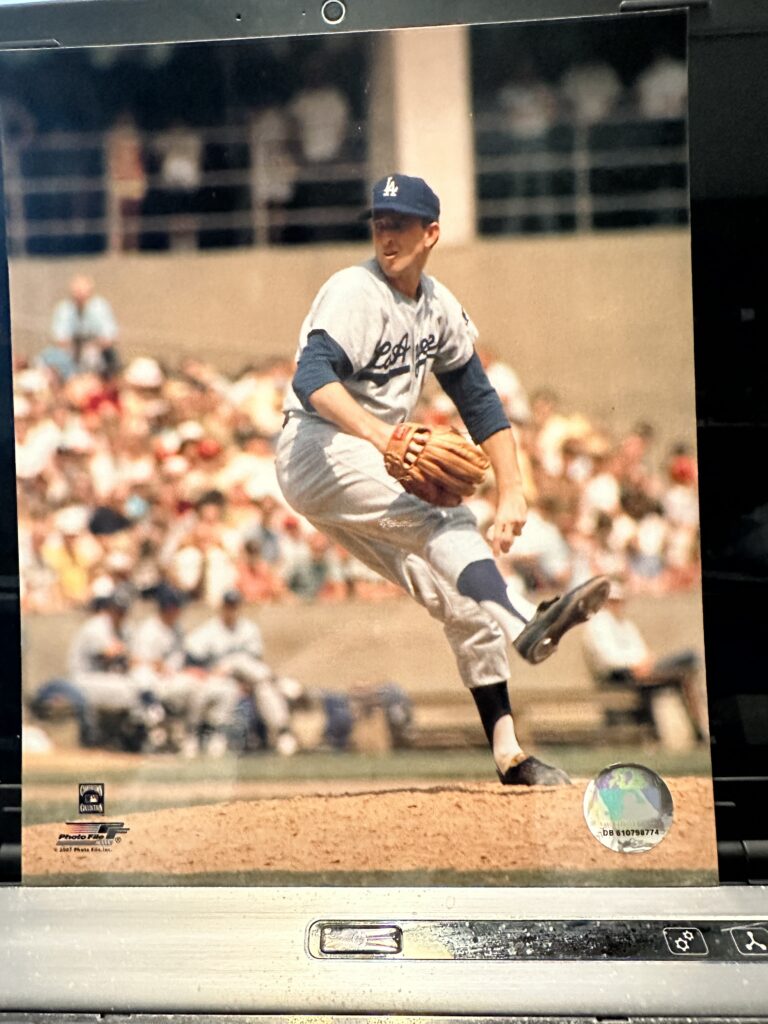

Little did he know how much that would come into play at the season’s most critical juncture. The Dodgers won the National League pennant behind not only Osteen but the two Hall of Famers-to-be atop their rotation, Sandy Koufax and Don Drysdale. Koufax went 26-8 with a 2.04 ERA and 382 strikeouts; he also pitched a perfect game (the fourth and final no-hitter of his career) and won the last of his three Cy Young Awards. Drysdale went 23-12 with a 2.77 ERA.

But the Minnesota Twins beat Drysdale and Koufax in the first two games of the Series, in the Twin Cities. Osteen was slated to start Game 3 back in Los Angeles, the 60th anniversary of which falls on Oct. 9 of this year. And during the flight home he remembers several of his teammates tapping him on his pitching shoulder and muttering encouragement as they passed his aisle seat.

“That kind of built the apprehension a little bit more than normal,” he said. “I was kind of a nervous wreck when I got off that airplane.”

Nor did it help that the Twins’ Zoilo Versalles, the American League MVP that year, spanked a ground-rule double on his first pitch of the game, a first-ball fastball.

But Osteen gathered himself.

“I had all kinds of pent-up energy, and I just needed to throw a pitch and get everything down to, ‘OK, let’s get on with the game now,’” he said. “I said, ‘OK, let’s go to work.’”

It helped that he knew Minnesota’s hitters. Osteen went 5-0 against the Twins during his three-plus seasons with the American League’s Washington Senators, before the Dodgers acquired him in a December 1964 trade involving slugger Frank Howard.

But certainly Osteen’s newfound resilience didn’t hurt, either.

He retired Joe Nossek on a come-backer, with Versalles taking third. That brought up the dangerous Tony Oliva, another future Hall of Famer. But Osteen set him down on a groundout, too. And after a walk to Harmon Killebrew, yet another Cooperstown-bound slugger, Osteen benefited from some good fortune.

With Earl Battey coming up, Twins manager Sam Mele called for a hit-and-run, an unconventional strategy with runners at the corners. But Battey missed the sign, and Versalles was trapped off third for the final out.

“It was like, ‘OK, here’s your break,’” Osteen said.

He would settle in, retiring 14 of 15 hitters before Versalles and Nossek singled with one out in the sixth. But Osteen again handled Oliva, inducing him to ground into an inning-ending double play.

The Twins also put two aboard with two outs in the eighth before Osteen popped up Nossek to end the inning.

He finished with a five-hit, 4-0 victory, as his teammates supported him with a 10-hit attack, the most notable being John Roseboro’s two-run single in the fourth.

Osteen told reporters afterward that his curveball, always his best pitch, had been particularly sharp, and that he benefited from a tailing fastball as well. (He acknowledges that it would be called a cutter today.)

The game represents a career highlight “by far,” he said. The Dodgers went on to win the next two games to take a 3-2 series lead. And while Osteen was beaten in Game 6, he again pitched well, allowing one earned run over five innings.

Koufax closed things out with a three-hit, 2-0 masterpiece in Game 7.

Osteen went 147-126 during his time with the Dodgers, made three All-Star teams and twice won 20 games in a season. Jim Murray, the legendary Los Angeles Times columnist, once wrote that he was “as dependable as sunset,” and manager Walter Alston declared that he “gets about as much out of his stuff as anybody in the majors,” per The Tennessean.

It was also while Osteen was in Los Angeles that he earned a nickname that stuck with him forever. Then as now, celebrities were regulars in the Dodger clubhouse, and one day actor Jim Nabors, star of the 1960s TV show “Gomer Pyle, USMC,” stopped by Osteen’s locker. Infielder Dick Tracewski took one look at the two of them and couldn’t help but notice the resemblance. So just like that, Osteen was dubbed “Gomer.” And he wore it, albeit uneasily.

“If you don’t like a nickname,” he said, “you don’t say you don’t like it.”

Certainly Osteen was the antithesis of his doppelganger, who was known for his bumbling ways. He went 196-195 while pitching for six teams over his 18 seasons. And when he considers his stats now – the 3.30 ERA, the 40 shutouts, the 140 complete games, the 0.86 ERA in three Series starts – he doesn’t see much difference between his accomplishments and those of All-Stars like the Yankees’ Andy Pettitte.

If you toss in the 15 years he spent as a pitching coach for four teams, Osteen appears to have a case for the Hall. He spent seven of those (1982-88) with the Phillies, and on his watch Steve Carlton (’82), John Denny (’83) and Steve Bedrosian (’87) earned Cy Young Awards.

Carlton, an all-time great, asked only that Osteen track his mechanical nuances, like whether he was consistently drawing his hands back during his delivery. Bedrosian also required some mechanical clean-up, seeing as there were times his arms and legs were “going in 12 different directions,” according to Osteen.

Denny was another matter.

“He was kind of a wild man inside,” Osteen said. “There was a little man inside that would break out of jail occasionally, and he would be another guy. He had demons going on, and there were certain people he didn’t get along with.”

During that ’83 season – a season in which the Phillies won the pennant but lost to Baltimore in the World Series – Osteen said he sat down with Denny after the right-hander hit a rough patch. The discussion was one-sided at first, by Osteen’s recollection, with him telling Denny that he seemed to be falling back into some bad habits, habits that had curtailed his effectiveness in previous seasons.

“In the process of my talk with him, he came very close to becoming that other man I’m talking about,” Osteen said. “I saw his eyes start to get glassy, and I thought, ‘Man, here we go.’ But he stayed there and he listened. And he got up and I gave him the floor, and he said, ‘I’ve got nothing to say.’ And walked out.”

It was nonetheless clear Osteen had made an impact on Denny, who in an interview years later called him “the perfect pitching coach for me.”

Osteen, a Tennessee native who grew up in Ohio before embarking on his nomadic career, moved with his first wife Georgie and their five children to the farm in Annville in 1975. They remained there through 1989. All their kids went to Annville-Cleona, and two of them pitched for the Dutchmen. Dave, a righty, led them to the 1981 Lancaster-Lebanon League championship, and in 1986 Gavin, like his dad a lefty, spurred them to a state title.

They too soaked up their share of knowledge from Claude, the result being that both turned professional and both reached Triple-A – Dave while in the Cardinals’ organization, Gavin while in the Oakland, Baltimore and Dodgers chains. Both have since gone into coaching/instructing, Gavin locally and Dave in the Dallas/Fort Worth area.

When asked about the primary lesson his dad taught him, Gavin unsurprisingly said it was the value of “just being a bulldog and always having the positives in your head and not the negatives.”

“Because,” he added, “the negatives will eat you alive.”

Claude was actually an A-C assistant when Dave was a senior, having taken a break from his major league duties for a season. And as with Bedrosian a few years later, the elder Osteen imparted mechanical tips – specifically, that his son should remove the ball from his glove earlier while winding up.

“I tried it and I didn’t like it, so I wasn’t going to do it,” Dave said with a laugh. “Had I listened to him, it might have made my career a little longer.”

Typical father-son stuff. And here’s the kicker.

“Now,” Dave said, “I’m teaching everything that he told me to do. I didn’t do it, but I remembered it.”

The bottom line is that Claude Osteen always had something worthwhile to say. But his best advice might have been that which he gave himself, as he sat alone with his thoughts, 60 years ago, in the quiet of a Southern California evening. And indeed it sustained him through the rest of his playing career, and informed him as he worked with others in the years that followed.

Questions about this story? Suggestions for a future LebTown article? Reach our newsroom using this contact form and we’ll do our best to get back to you.

Keep local news strong.

Cancel anytime.

Monthly Subscription

🌟 Annual Subscription

- Still no paywall!

- Fewer ads

- Exclusive events and emails

- All monthly benefits

- Most popular option

- Make a bigger impact

Already a member? Log in here to hide these messages

Quality local news takes time and resources. While LebTown is free to read, we rely on reader support to sustain our in-depth coverage of Lebanon County. Become a monthly or annual member to help us expand our reporting, or support our work with a one-time contribution. Cancel anytime.