What drives someone to be successful?

While there are many answers to that question, in the case of Lebanon County native James Lick, the answer was simple.

“His initial ambition was to show up the father of his girlfriend, and he definitely did that,” says local historian Kathy Bicksler Stouffer. “He had goals and he was driven to reach those goals and he had all the tools that were necessary: the intelligence, the drive, to get to what he wanted to accomplish.”

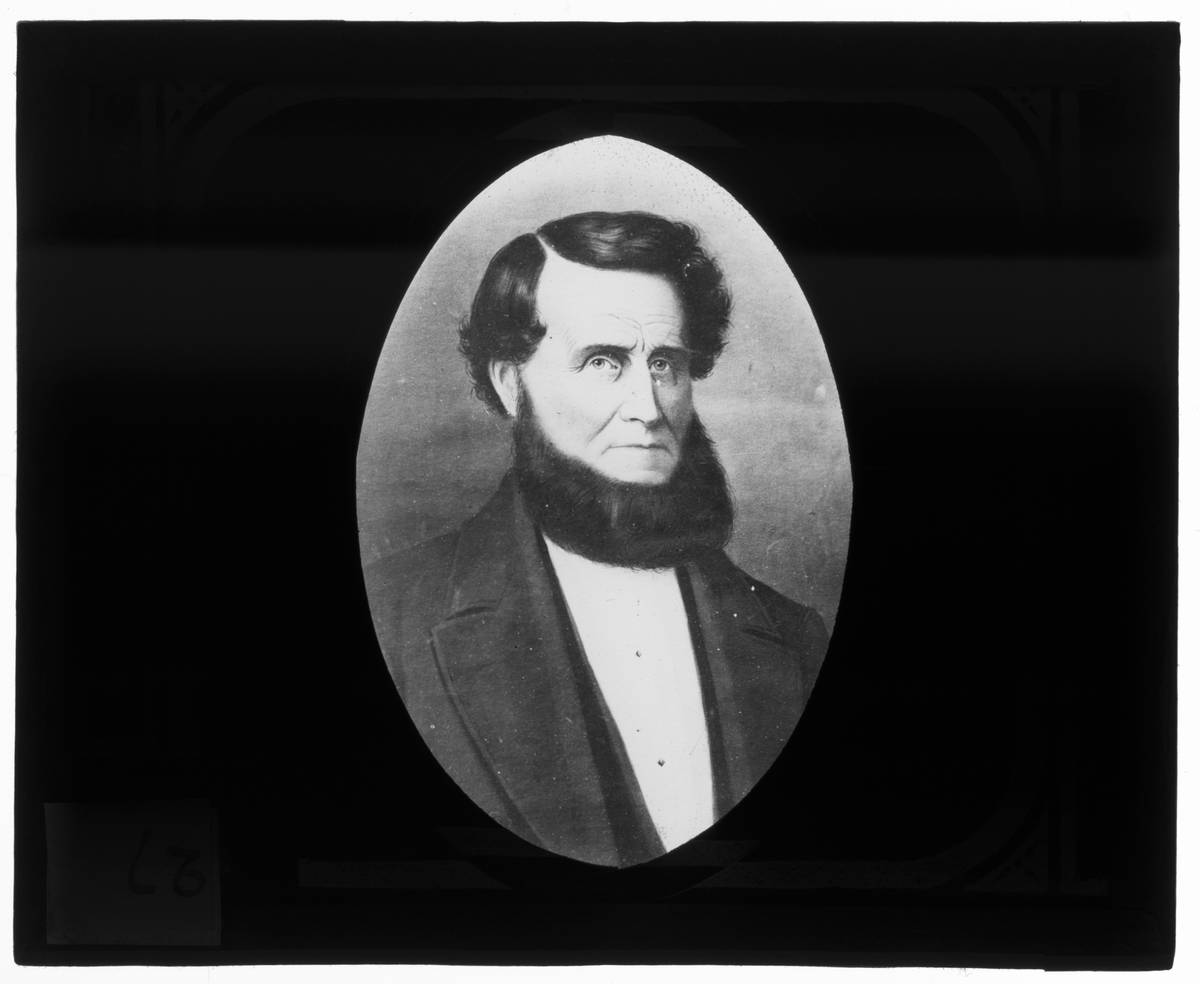

Lick, who was born in Fredericksburg on Aug. 25, 1796, contributed greatly to the benefit of society during his lifetime. Because of his wealth and as a man who never married, he was a philanthropist who donated his vast wealth to various causes.

“And I think that not only did he succeed in accomplishing his initial goal, but he more than succeeded to die as the richest man in California,” Stouffer added. “When you compare his wealth to even some of the wealthy people now, his was really pretty significant.”

Lick began to learn woodworking at the age of 13 in what would be but one of several careers during his life. He became his father’s apprentice and learned the business of building cabinets and other furnishings. He would also become a real estate investor, land baron, furrier, and a patron of the sciences.

As a young man living in Lebanon County, Lick fell in love with Barbara Snavely. However, her father, mill owner Henry Snavely, refused to give Lick his daughter’s hand in marriage, probably since Lick hadn’t accumulated wealth.

Lick’s motivation was on full display when he reportedly told Henry that one day he would own “a mill that makes yours look like a pigsty!”

Driven by Henry’s rejection, Lick left Lebanon County for Baltimore to learn how to make pianos. Barbara was pregnant with Lick’s child, and historians have written that he left Lebanon County to earn enough money that Henry would allow him to marry her.

Lick left Baltimore for New York to open his own piano business. When he learned his pianos were being shipped to South America, Lick used his intelligence to grow his wealth through that business, according to Stouffer, co-author of the local history book, “Fredericksburg, Lebanon County, Pennsylvania.”

“And then he said, ‘Wait, I can make a lot more money if I go to where these pianos are being sold,’” said Stouffer. “So he went to South America (in 1821) to sell them because he could cut out the middleman. The guy said, ‘This is what I want to do. This is what I want to accomplish.’ And he did it.”

Lick would return to Lebanon County a few years later with what he believed to be enough money to marry Barbara, but there was one problem: she had married someone else. Consequently, Lick remained a bachelor for the rest of his life.

“It seems to me like he either stayed infatuated with her – certainly for a period of time – because he did go back to try to show her father that he had the money to marry her. But then she was already married,” Stouffer said.

Stouffer said that historic records indicate that she was pregnant again less than nine months after getting married.

“When you do the math on when the baby was born, her first child, it was less than nine months, so I think she was pregnant again,” Stouffer said. “And I think her father, you know, was prestigious, but I think the fact that she was pregnant again was probably more of a thing of like, ‘Hey, wait a minute, you know, I better give up the hand here.’”

Her first child, John Henry Lick, lived his entire life in Lebanon County, and was one of James Lick’s six legacies in the county given his many contributions to the area.

“I count as one of the things he really contributed to Lebanon County was his son, John Lick, because he really had a big influence (here),” said Stouffer.

Dejected that Barbara was married, James returned to South America, but war led him to move to Chile and then Peru for a time before heading back to the United States in 1847. Stouffer said he sailed to California that year and arrived in San Francisco just prior to the California gold rush. (Lick traveled with his tools, workbench, and a fortune of $30,000 in Peruvian gold (modern-day equivalent of about $1.2 million), according to Stouffer.

Stouffer said he traveled with something else – a massive amount of chocolate he brought with him that he had bought from his neighbor in Peru. That neighbor, Domingo Ghirardelli, was the founder of the famous candy that’s still based in San Francisco today.

“The chocolate sold so quickly that he wrote to his friend Ghirardelli, and he had a chocolate shop next to Lick’s cabinet shop in Lima, Peru. And he urged him to move to San Francisco.

“That was in 1847, and he did, I think, (move) in 1848 or 1849,” Stouffer said. “He (Lick) was so convinced that San Francisco was going to grow that he invested in real estate and, of course, they discovered gold in the fall of 1848 and then the Civil War increased the demand for the produce, lumber and gold and silver produced by California. So in addition to all those people coming to California and him getting the land, the Civil War also made him wealthy.”

Lick would live the rest of his life in San Francisco and even attempted to lure John there so that he could be near his son. John did visit his father but historians said he couldn’t acclimate to California’s climate and he tended to disagree with his father, so John returned to the Lebanon Valley.

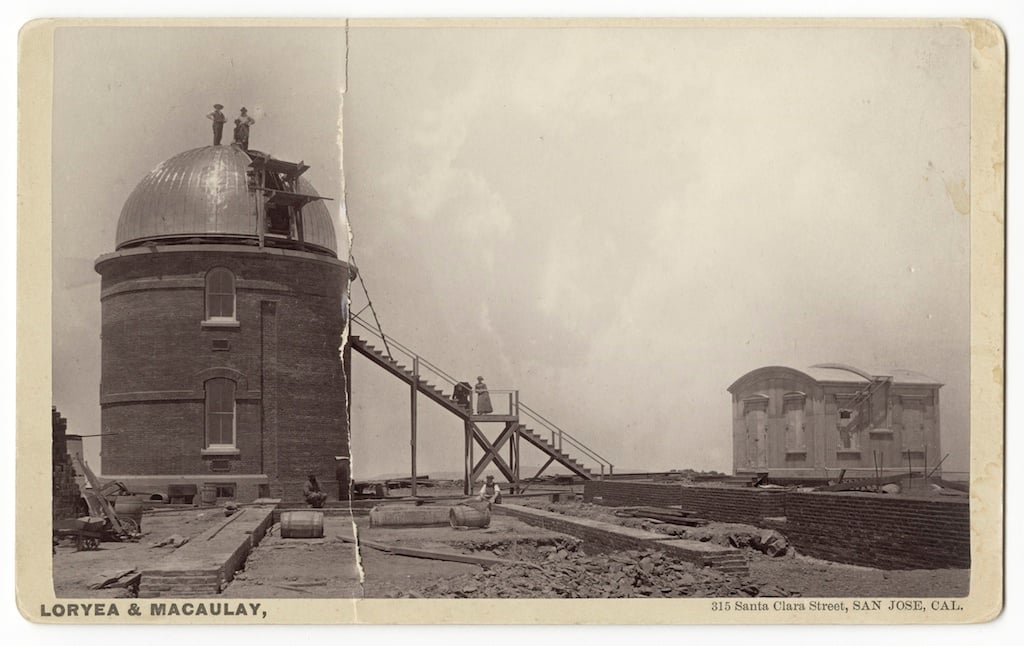

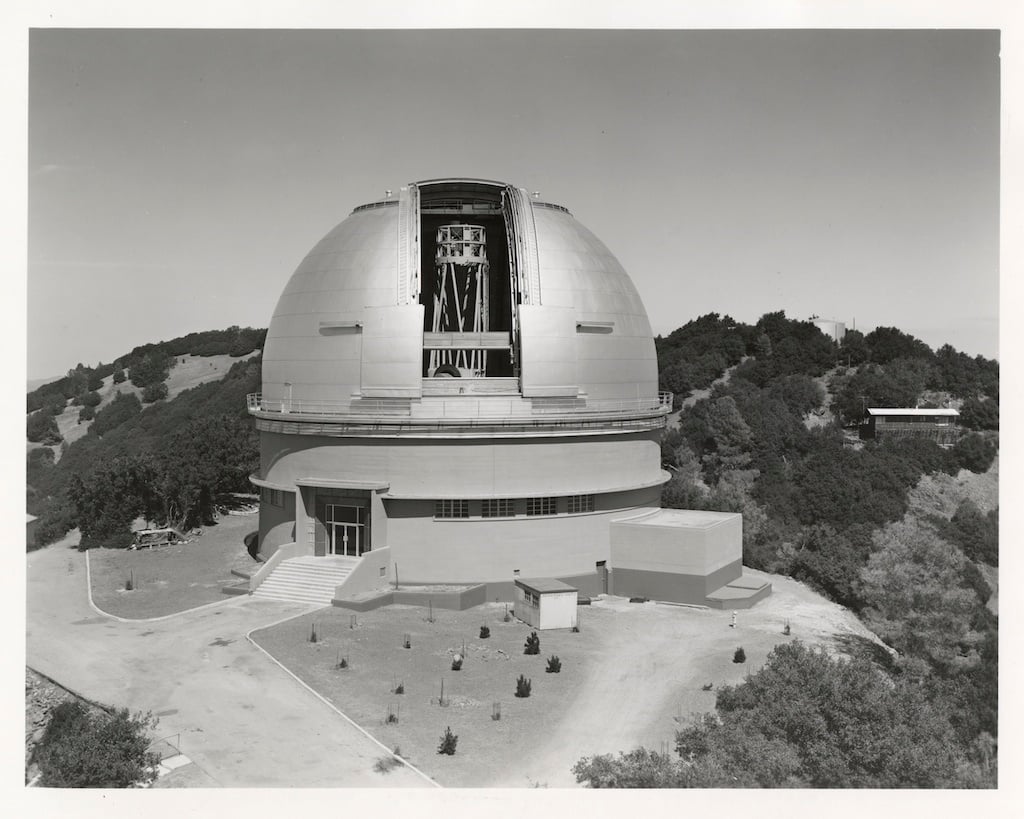

James made numerous contributions to the San Francisco area. His most famous achievement was the founding of the Lick Observatory and the Great Lick Refracting Telescope located in Mount Hamilton.

Maryanne Campbell, communications specialist at University of California Observatories, said James Lick was a visionary.

“He invested his fortune into creating a world-class observatory, demonstrating foresight, dedication to science, and a desire to leave a lasting impact that extended far beyond his own lifetime,” Campbell wrote in an email to LebTown. “Even though Lick himself wasn’t a scientist, he had the vision to fund the world’s first permanently occupied mountain-top observatory, a bold and unprecedented idea in the 1870s. He wanted to create a legacy that would advance human knowledge. His insistence on building the most advanced observatory of its time shows remarkable foresight.”

Campbell noted that James Lick did not live to see the first observations at Lick Observatory. He died in 1876, and the observatory’s 36-inch refractor telescope (the world’s largest at the time) wasn’t completed and used for its first observations until 1888.

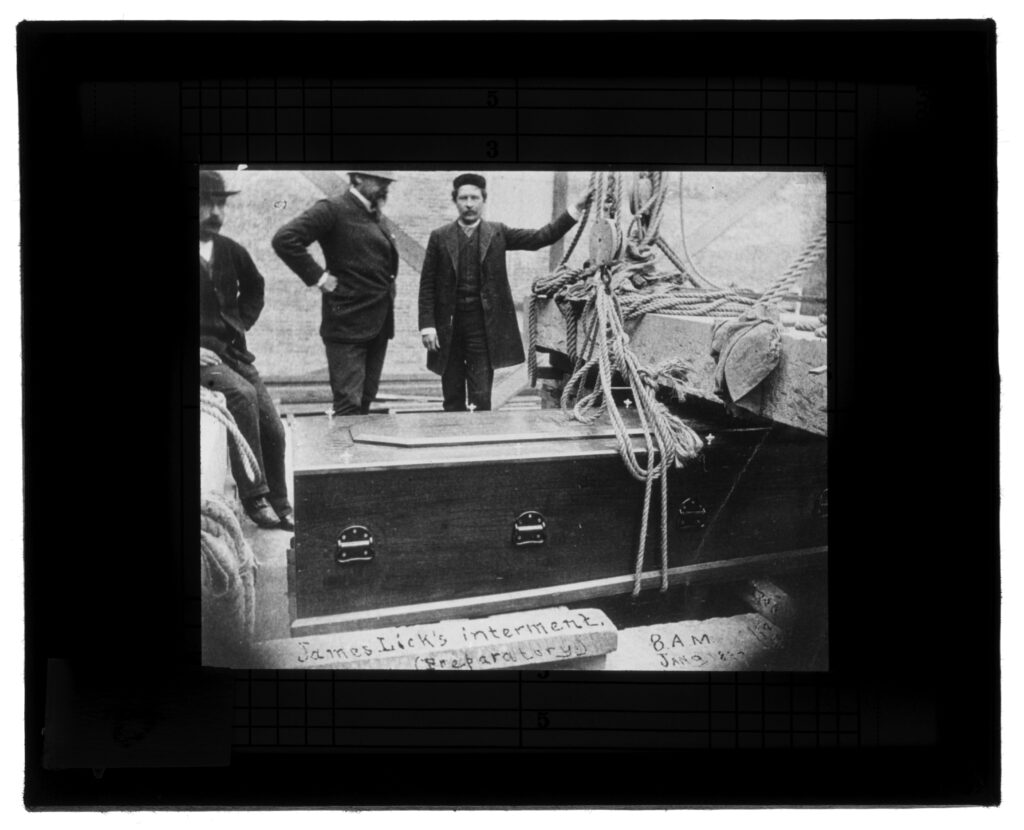

“James Lick made the decision in 1874, two years before his death to be interred beneath the 36-inch Great Refractor. Originally, he had considered other legacy projects (like building giant monuments in San Francisco), but he was persuaded by astronomers and academics that a world-class observatory would be a more lasting contribution. His tomb lies directly under the pier of the 36-inch Great Refractor at Lick Observatory,” Campbell wrote.

Lick spent a portion of his vast fortune constructing Lick House Hotel, which stood until the San Francisco earthquake of 1906. He also contributed to the Conservatory of Flowers, in Golden Gate Park, in honor of his friend, Francis Scott Key.

He founded the free James Lick’s baths in San Francisco, which provided a bathing facility for people when most residents didn’t have indoor plumbing, and established the California School of Mechanic Arts. Pioneer Monument, in front of San Francisco City Hall, a series of bronze statues illustrating the history of California, is another of his contributions, as is the Lick Old Ladies’ Home, a former retirement facility for impoverished widows.

He also left money in his will to Lick family members, many of whom lived in Lebanon County and were mostly distant relatives. That, according to Stouffer, is another Lick legacy to Lebanon County. One such relative was Maggie Lick Grumbine who received $1,000 annually from around 1877 until her death at age 92 in 1970.

“For at least 100 years, he was giving, his foundation was giving, money to his Lick relatives. So that’s definitely a Lebanon County (legacy),” Stouffer said. “When I did quick research about genealogy, I don’t think her mother’s father was even his brother. So more than just relatives, he was giving money to all these relatives that weren’t real close. I mean, at the very closest, she would have been a great niece. And she was getting $1,000 every year.”

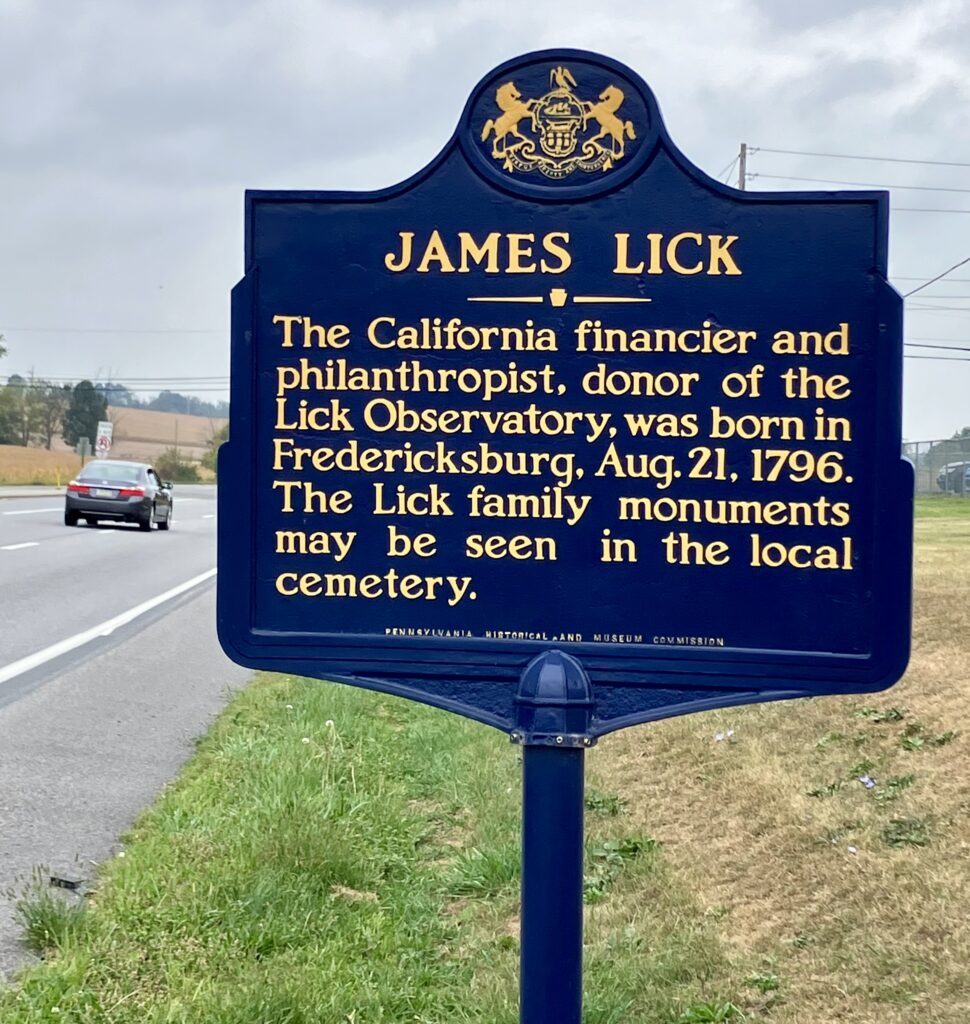

Other local legacies, according to Stouffer, include James being born in Fredericksburg, which also has its only historic marker in his honor, the town of Lickdale named after him and son John, and the Lick monument that’s located in Fredericksburg’s Cedar Hill Cemetery. (Following in his father’s footsteps, John Lick created the Sentinel Monument in that cemetery.)

Read More: Statue rededication ceremony honors Lebanon County’s Civil War veterans

“The original idea for him (James) was to leave a monument in his hometown to honor his grandfather who fought in the Revolutionary War,” Stouffer said.

PA Marker’s website says James “bequeathed generous amounts of the estate to his son and other relatives, and ordered the construction of an enormous marble monument over the graves of his parents and grandfather in Fredericksburg, with the rest of his money to fund public projects. A board of trustees, his son John Henry among them, was appointed to oversee operations and make sure what his father wanted was done.”

There were a few other notable recognitions, including the naming of James Lick Middle School in San Francisco and James Lick High School in San Jose.

“There’s the asteroid 1951 Lick and also a lizard called Sceloporus Licki,” Stouffer said. “There is a crater named after him on the moon. But I think the observatory, his biggest project, is the one that he spent $700,000 for the land observatory and the telescope. Completed in 1888, it was the first permanently staffed mountaintop observatory with the largest refracting telescope in the world at that time.”

He died on Oct. 1, 1876, in the Lick Home in San Francisco at the age of 80.

Questions about this story? Suggestions for a future LebTown article? Reach our newsroom using this contact form and we’ll do our best to get back to you.

Keep local news strong.

Cancel anytime.

Monthly Subscription

🌟 Annual Subscription

- Still no paywall!

- Fewer ads

- Exclusive events and emails

- All monthly benefits

- Most popular option

- Make a bigger impact

Already a member? Log in here to hide these messages

Local news is disappearing across America, but not in Lebanon County. Help keep it that way by supporting LebTown’s independent reporting. Your monthly or annual membership directly funds the coverage you value, or make a one-time contribution to power our newsroom. Cancel anytime.