What does baseball great Babe Ruth have to do with Lebanon, Pennsylvania? Driving past the Bethlehem Steel complex today, it’s not easy to imagine the fortunes this plant once produced, so wealthy that it once paid Babe Ruth, eventually America’s most famous slugger, a year’s salary to play a single game.

In 1914, Bethlehem Steel had 16,000 workers. By 1917, after America had entered “The Great War” (known today as World War I), Bethlehem Steel employed 35,000 workers and was producing 800 percent profits as the third largest company in the nation (after US Steel and Standard Oil).

Carnegie protege Charles M Schwab left U.S. Steel to helm Bethlehem Steel in 1904 (originally founded as the Saucona Iron Company in 1857). Bethlehem Steel went on to acquire numerous companies and expand rapidly, but it wasn’t until 1916 that the firm picked up Lebanon’s American Iron and Steel Manufacturing “central works” in Lebanon.

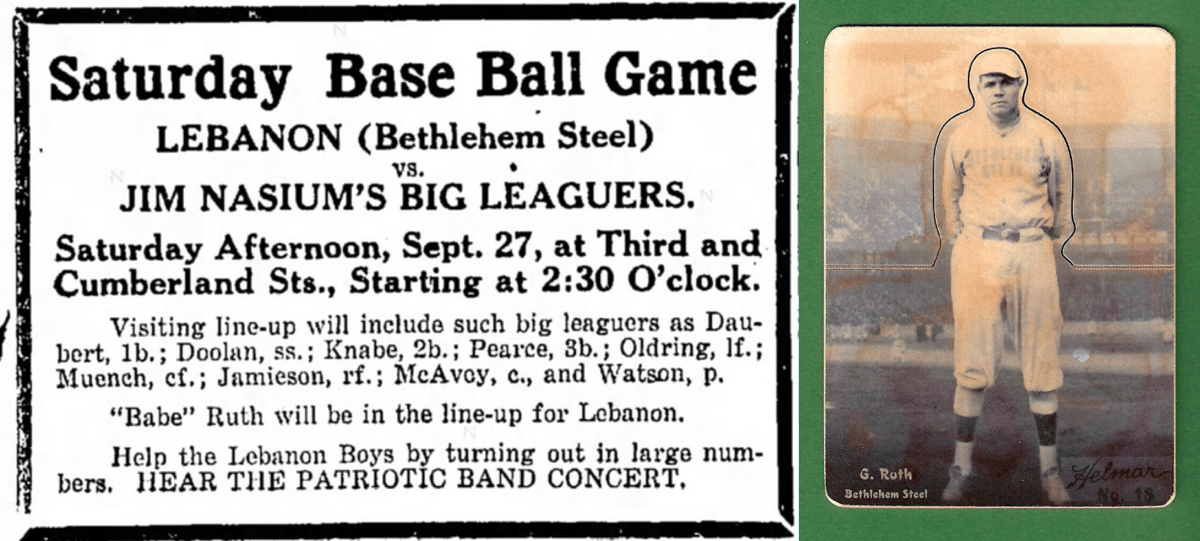

With a network of sites across the state, Schwab had begun the baseball league he called the Bethlehem Steel League before hostilities actually commenced. Early on, the teams drew from labor forces and perhaps a few semi-professionals. As this newspaper clipping demonstrates, significant appropriations were made towards recreation.

Schwab was quoted as telling his executives, “I want some good wholesome games that will furnish amusement and entertainment for the Bethlehem Steel Company’s employees, and don’t bother me about details of expense.”

The league had peers across the state, with the Philadelphia Public Ledger regularly reporting standings and happenings.

As a close read of the above article indicates, there was a controversy of sorts brewing about the idea of professional players in the league—”Any ball player in the local yards is doing his bit the same as all the others.”

The Bethlehem Steel League consisted of teams from the six main plants: Bethlehem, Lebanon, Steelton, Wilmington, Fore River, and Sparrows Point.

In May 1918, the Selective Service Division issues its Work or Fight edict, and so after the season ended in September, players flocked to the industrial leagues. George “Babe” Ruth was known as “baseball’s most sensational representative” at the time, and he was just coming off a 4-2 World Series win playing for the Red Sox. (This world Series saw low attendance and was held early due to the Work or Fight order. It was also the first World Series to feature the Star Spangled Banner, played during the seventh inning stretch.)

Not long after the World Series, Ruth was paid $1,300 to pitch in a game between two New England industrial teams (far more than the $1,100 he received for playing in the six World Series games).

On Friday September 20, 1918, the Daily News reported that the great player was in town looking for “essential employment.” However the discussion (or negotiation) that day proved inconclusive, with the paper noting that “he left again in the evening without promising to return here to work.”

Ruth was back next week staying the the Hotel Weimar. The Daily News reported that Sam Agnew, a former Sox catcher, was already employed at Lebanon and that his friendship with Ruth was a likely reason for the slugger to stay put in Lebanon.

A couple days later, the Lebanon Daily News passed along a report from the Patriot-News that the “demon slugger completed negotiations with [Charles] “Pop” Kelchner, physical director at the Lebanon plant, yesterday and immediately reported at the plant for work.” Kelchner was football and baseball coach at Albright College and later a professional baseball scout.

Babe’s first game and only game for Lebanon was September 27, 1918 at the field formerly at Third and Willow street. (The address was actually Third and Green, but Green Street is no longer extant along large portions of the Quittie).

In that first and only game, Ruth wasn’t mentioned on the line-up, and according to other accounts, he was actually originally planned to play in the Delaware River Ship League, along with Joe Jackson and Rogers Hornsby. The Delaware River League was known to be more competitive given its nickname as the “SafeShelter League”, and Jackson was quoted as saying it was “harder to hit in this league than in the American League.”

The September 27, 1918 exhibition game was against Jim Nasium’s all-star lineup.

While living in Lebanon, the Ruth’s comings and goings were considered news. But not all the happenings made print. For one, Ruth in all likelihood did not deliver a single blueprint in his tenure for Bethlehem Steel as a blueprint messenger. For another, he may have had an affair in Myerstown, and ditched a huge butcher bill in Lebanon (these allegations according to Harris B Light, a Lebanon native interviewed by the Chicago Tribune in 1987). While in Lebanon, Ruth also resided at 718 Chestnut Street (now the VFW building) and 34 East Locust Street.

Ruth was expected to play at an additional exhibition game the next weekend, but did not appear. The reason would later be reported as he had become afflicted with the Spanish flu and had retired to Baltimore for recuperation. Ruth would not play for Lebanon again.

In an editorial published after Armistice ended the Great War on November 11, 1918—after the major leaguers had left town—the Lebanon News opined, “The baseball public will being to see that the players merely used the steel mills and the shipyards as a shield for their personal ambitions.”

This sentiment echoes what another Lebanon native told the Chicago Tribune when they visited in 1987. Ralph W. Clemens, who umpired semi-pro baseball games just like his father, recalled being a late teen when Ruth came to town:

”Why, the whole gang of them was draft dodgers. They were supposed to be working for the war, but they didn’t do any work. All they did was play baseball. Babe Ruth used to show up at the plant for an hour before practice. He’d be wearing fancy trousers, silk shirts and patent-leather shoes. He’d just walk around talking to people about baseball. There wasn’t anything essential about what he was doing.”

Lebanon native Ralph W. Clemens on Babe Ruth coming to town

Yet Ruth’s time in Lebanon remains a point of pride, and memorabilia from the Bethlehem Steel days make a popular attraction not just at the County Historical Society but also in other traveling exhibitions across the country. It’s a reminder that Lebanon has brushed with greatness in the past, and a fable that it might one day again in the future.

Thanks to Pat Rhen for sharing links that helped with this post.