High up in the northern mountain ridges of Cold Spring Township, a largely unmarked trail leads to one of the great natural wonders of Lebanon County in the form of the Boxcar Rocks.

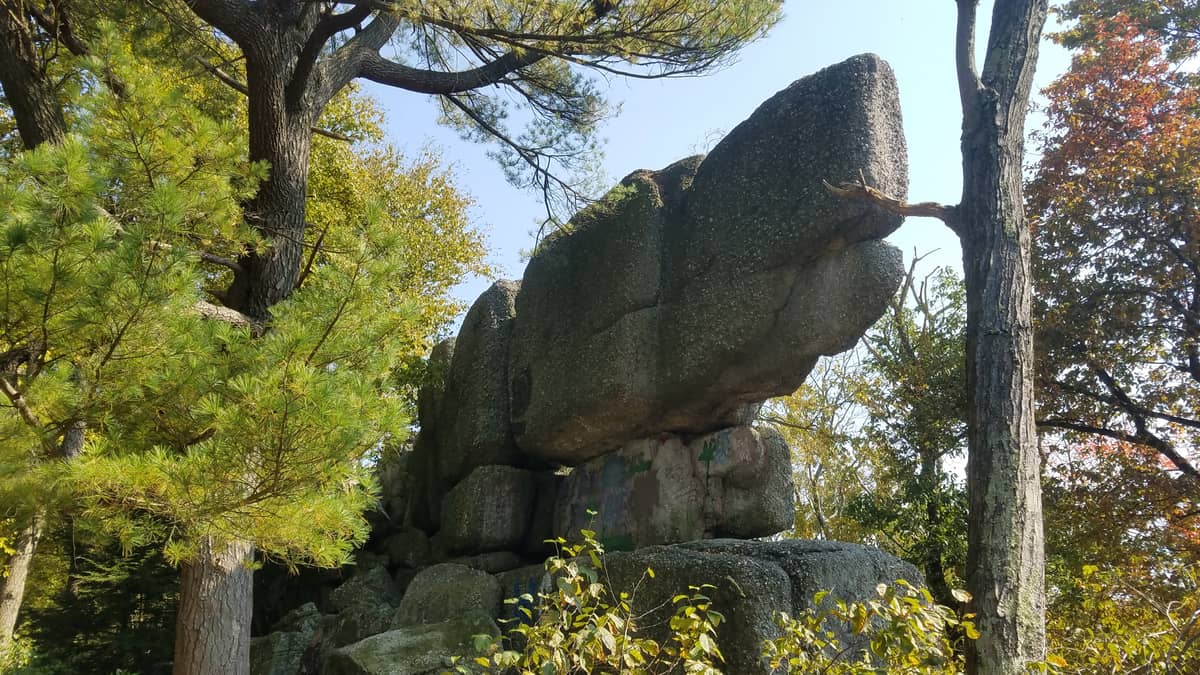

The Boxcar Rocks, also known as the Chinese Wall or the High Rocks, are composed of a long line of stacked, blocky conglomerate boulders perched over Stony Valley. Though somewhat remote, the rocks are easy to reach and are a great all-around hike for people of varying skill levels.

The rocks are accessible through a public trail on State Game Lands #211. The trail begins at a rocky parking lot just off of Gold Mine Road in Cold Spring Township. It’s easy to miss the entrance, on the right side of the road if heading north, so here’s a GPS coordinate that will target the right place: 40.544541, -76.535690 (Google Maps).

Once past the gate, the trail begins. While the trail runs far into the game lands, the Boxcar Rocks are most easily accessed at a turn-off several hundred feet along the right side. This even shorter path leads to a clearing, and the formation itself is on the hill behind it. In all, the rocks can be reached in about 10 minutes or less of hiking.

The rocks are part of a geologic formation that runs along the Sharp Ridge, one of several mountain ridges that runs through the northern end of Lebanon County and surrounding areas. The distinction (if there is one) between the Boxcar Rocks and the Chinese Wall is unclear, but both nicknames can be found on maps.

Read More: A trek into the wilderness of the Lebanon Reservoir and Jeff’s Swamp

The formation itself is believed to date back 300 million years or more and is composed of a quartz-pebble conglomerate rock type, sometimes referred to as Pottsville conglomerate after the Schuylkill County seat further up the Sharp Ridge. The material that makes up the rocks was washed into the area from earlier, ancient mountains in the Reading area and gradually cemented into sedimentary layers over time.

Read More: What exactly is the “Jonestown Volcano”?

Eventually, the once-underwater rocks were “crumpled” up into the mountain ranges that weave through eastern Pennsylvania as a result of tectonic plate collision between early forms of North America and Africa. Over time, the forces of erosion wore away the softer exposed rock, leaving behind the unusual blocky appearance of the remaining conglomerate.

The rocks have been a longtime landmark of the area and are said to have been a camping ground for Native Americans. In the 20th century, the rocks became a favorite hike for Boy Scouts and other outdoor groups. According to historian Brandy Watts, who maintains the informational website StonyValley.com, the rocks were often a picnic destination for local families during the Great Depression.

Read More: Stony Valley opens up Oct. 18 for annual drive-thru tour, back on after cancellation

Watts also writes that they got their nickname in the 1940s from Lebanon chemical manufacturer and publisher Harry D. Lentz, who was one of the driving forces behind the creation of Gold Mine Road. Lentz described the rocks as a “Railroad Wreck of Boxcars,” and the description caught on.

While some of the upper reaches of the rocks are accessible, only skilled climbers should attempt going for the tops; there are no rails or other safety measures at the site to prevent falls. These sections are frequently only a couple feet wide or less and drop offs on both sides can go down dozens of feet. Those who can scramble to the top are treated to a wonderful view of the surrounding valleys, but there’s plenty of comparable views to be found on more solid ground as well.

While walking around the “rubble,” it’s a good idea to stick to the stones. The fissures and gaps between the rocks can sometimes be covered up by debris and, in autumn, piles of leaves.

In 2003, the site was added to the Schuylkill County Natural Areas Inventory. Approximately two thirds of the formation reaches past Lebanon’s borders.

Camping is prohibited in the area, but the occasional charred campfire can be found. Graffiti has also been a recurring nuisance on the rocks, but it’s less common in the more remote stretches of the ridge.

Though the rocks sit at an elevation of around 1,500 feet above sea level, the gain from the parking lot is minor. There’s a lot of freedom in approaching the hike: while formal trails aren’t marked, eagle-eyed hikers will be able to spot pathways continuing far up the ridge and make their visit as long or as short as desired.

It’s also worth checking out the ridge from the opposite side, where the immensity of the “wall” becomes apparent. It’s a bit steep, but some of the most impressive perspectives of the rocks can be found from the side of its base that slopes into the valley.

If you decide to head out, it’s a good idea to go with a group or let someone know where you’re going. It’s common to be entirely alone in the area, which can be both a blessing and a curse. Keep aware of hunters while on the game lands, especially during game seasons. This section of wilderness is also home to snakes and other animals. Timber rattlesnakes, one of the more dangerous critters to call the Stony Valley area home, tend to be less of active during colder weather.

Questions about this story? Suggestions for a future LebTown article? Reach our newsroom using this contact form and we’ll do our best to get back to you.

Keep local news strong.

Cancel anytime.

Monthly Subscription

🌟 Annual Subscription

- Still no paywall!

- Fewer ads

- Exclusive events and emails

- All monthly benefits

- Most popular option

- Make a bigger impact

Already a member? Log in here to hide these messages

Free local news isn’t cheap. If you value the coverage LebTown provides, help us make it sustainable. You can unlock more reporting for the community by joining as a monthly or annual member, or supporting our work with a one-time contribution. Cancel anytime.