The Swatara Creek begins in the mountains of Schuylkill County, coursing over 70 miles to the southwest through Lebanon and Dauphin Counties before emptying into the Susquehanna River near Middletown.

It’s one of the major bodies of water in Lebanon County, and since 2012, eight miles of its length have been contained within the large 3,520-acre Swatara State Park. The park itself is the end result of a complex, ambitious, and ultimately incomplete plan that would have added a dam on the river at the Swatara Gap near Green Point and created a miles-long lake stretching out across the northern end of the county.

Dams on the Swatara

The Swatara currently has two small dams on it, one operated by the City of Lebanon Water Authority in Jonestown and the other by the PA American Water Company for residential service. In comparison, the proposed dam would have measured 40 feet high and 500 feet wide with a 750-acre impoundment behind it, flooding nearly seven miles of land from Green Point out to Suedberg in Schuylkill County.

Read More: [Photo Story] Brilliant blues and fiery fall colors on display at Swatara State Park

Though the idea of a modern dam on the Swatara has frequently been claimed to date back to 1969, newspaper records show it was actually considered as far back as May of 1960, when Greater Lebanon Refuse Authority chairman Franklin Z. Meiser “threw out” the idea of a new dam project at Inwood during a courthouse meeting with the Lebanon County Commissioners. Meiser subsequently stated that he had first conceived the idea even earlier in 1955, when he was a member of the Regional Planning Commission.

The new dam initially had smaller dimensions, with early plans calling for a 25-foot breast. This number and others, like the estimated cost of $3 million, grew as Meiser and proponents of the idea continued to develop the project.

Dams on the Swatara weren’t unheard of at the time of the proposal. A long-gone dam on the creek existed between 1826 and 1862, comprising a 45-foot breast and an 800-acre impoundment that ran six miles northward in the direction of Pine Grove. The existence of this dam (used for the management of the Union Canal) was brought up in discussions on the new one.

Besides the historic predecessor, dam proponents pointed to the Swatara’s potential for fishing as another reason to consider the project. Historic accounts of the creek’s natural populations were cited in early meetings as proof of the possibilities.

Water supply and pollution concerns

One of the most important roles of the dam would have been to provide a major new source of water for Lebanon County. Concerns that the current water supplies available to the Lebanon system would be insufficient in the oncoming decades would have been laid to rest if the reservoir was created. At the time, Lebanon’s major source of water was the High Bridge Reservoir near Pine Grove, which had a capacity of about 310 million gallons or so. In comparison, the Swatara reservoir would contain around 3.3 billion gallons — over ten times High Bridge’s volume.

Read More: A trek into the wilderness of the Lebanon Reservoir and Jeff’s Swamp

If the reservoir became a reality through the use of state funding, the City of Lebanon would be billed for any water taken from it. In June of 1963, the system drew over 100 million gallons from the High Bridge Reservoir and over 76 million from its second source, a small intake facility already on the Swatara near Jonestown.

But one of the biggest problem facing the project was in direct conflict with its future as a water supply: pollution. Acid runoff originating from abandoned strip mines and coal silt was known to be a major issue even in the project’s early days, and many locals could plainly see that the “Black Swattie” was not nearly as clean as it should be.

Proponents of the project, including Meiser, suggested that limestone impoundments could be used to neutralize the creek’s acid content. This technique, known as “liming,” is still used to return acidified bodies of water back down to safe levels.

Still, the seepage threatened to overwhelm any preventative measures since there was no way to effectively seal off the mines from the watershed. This was also a problem at the High Bridge Reservoir as well, a fact that was cited early on as a reason to pursue the project (the reasoning being that water from the area was already being managed and used in the system).

Public and official opinions clash

Any project as large in scope as the Swatara Dam draws mixed opinions and often heated debate. While generally favored by officials at both the local and state levels, the dam was an unpopular prospect for families who would be forced to vacate their homes to make way for the reservoir and park, as well as citizens who doubted the state’s capacity to take care of the creek’s acid problem.

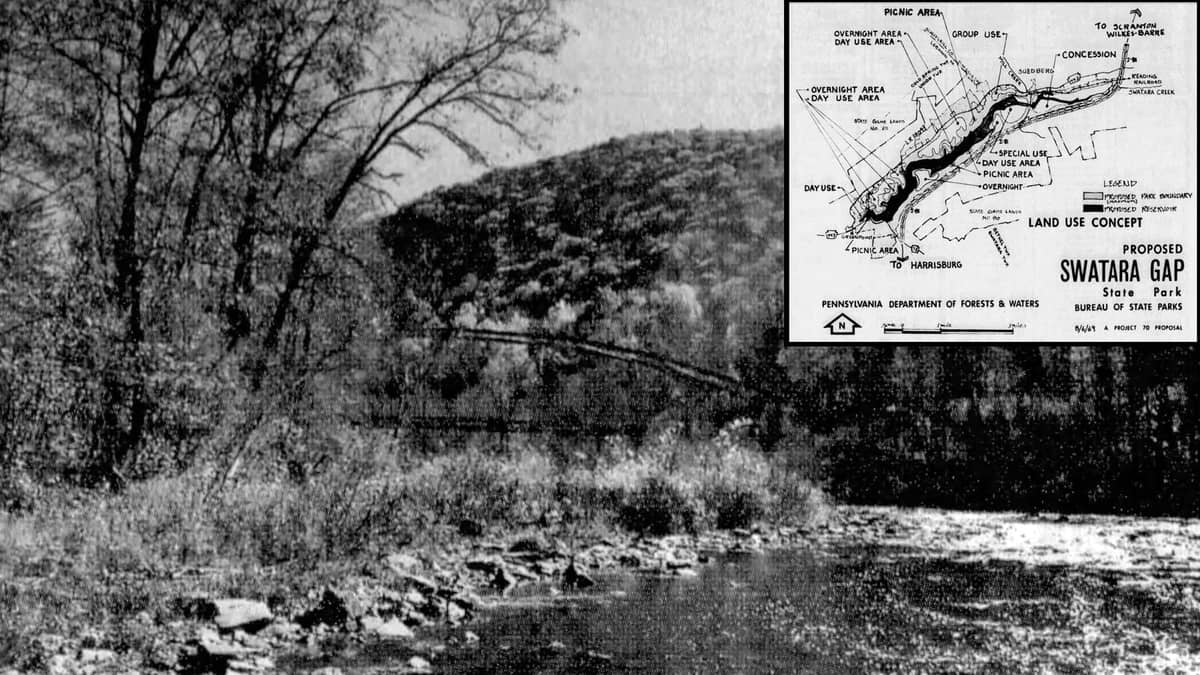

In August of 1969, Dr. Maurice Goddard, Pennsylvania’s Secretary of Forest and Waters and one of the project’s staunchest supporters, unveiled a map of the proposed reservoir and state park to a crowd of 500 officials and citizens at Northern Lebanon High School. The project at that point was estimated to cost around $7 million and would have a completion date around 10 or 15 years into the future.

At this event, the Citizens Conservation Association of Lebanon County spoke against the plan, with opponents claiming the unlikelihood of fixing the Swatara’s pollution problems permanently. CCA secretary Richard Henry stated that there was no permanent solution for treating the Swatara’s acid problem and described the plan as “economically unsound.”

In response, County Commissioner John Anspach made a statement expressing his and the other commissioners’ support of the project, a sentiment also shared at the time by Mayor Jack Worrilow, Lebanon City Council, the Lebanon Bureau of Water Sewage, and many other community leaders and organizations.

A major setback and land acquisition

One possibility for the dam to move forward was through Project 70, a 1964 state law allocating $70 million for use in acquiring land for public parks, reservoirs, historical sites, and other preservation efforts. Secretary Goddard had claimed in 1963 that the Swatara dam project would meet all the requirements for the then-unpassed law, and Project 70 was seen as the answer to the question of funding throughout the rest of the 1960s.

But in 1970, as Governor Raymond Schafer signed the “Swatara State Gap Park” into conceptual existence, officials found out that the entirety of the Project 70 funds had already been used on other projects. This was a serious blow to the project. For months, the Swatara Dam and state park hung in limbo.

Goddard, still one of the project’s biggest supporters at the state level, continued to fight for it in his position as secretary of the newly-created PA Department of Environmental Resources, established after the Department of Forest and Waters was abolished in 1970. The DER itself later split into the Department of Environmental Protection and the Department of Conservation and Natural Resources in 1995.

Early in 1971, the project was approved for a $2.7-million grant by the General State Authority, one of 17 grants for park projects around the state totaling $13.3 million in all. Now it was time for the next phase of the project to begin: land acquisition. Over the course of the decade, the state began piecing together the massive acreage of the project through land purchase and use of eminent domain. This included the acquisition and subsequent destruction of residences and farm operations within the project’s borders.

It’s this period of land acquisition that still stings for many of the residents displaced and affected by the project.

By the late 1970s, around 200 parcels of land had been acquired by the state, funded by the 1971 grant as well as a supplemental 1974 grant of $1.7 million. A 1977 series of articles written by Lebanon Daily News reporter Paul Keiser detailed the history and future of the project, which was now estimated to cost around $25 million to complete due to projected inflation.

Keiser reported that three of the plan’s biggest obstacles had been “largely eliminated,” according to state officials. These included a rerouting of Route 72 (deemed less prohibitive thanks to the construction of Interstate 81) and the presence of an active Reading Railroad line (which its operators were willing to give up for several hundred thousand dollars). The third problem, pollution, was declared to have changed significantly since the 1960s thanks to millions spent on improvement projects, though it was still not known when the water would be brought down to acceptable levels.

The acquisition of the remaining land was now believed to be the last objective standing in the way of construction.

Further progress and delays

Work continued haltingly in the 1980s, though more than $40 million was allocated for the project at this time. The last of the land was acquired in 1987, when it was announced that work would begin soon, with the dam expected to be complete by 1989.

Goddard, who had retired from the DER in 1979, urged locals to put pressure on legislators to keep the project moving at a Municipal Building meeting in 1988. The dam was by then scheduled to be finished by 1991.

The relocation of Route 443 was yet another hindrance to construction, but its new three-mile reroute was finished in 1993. Still, the project seem to always be perpetually two or three years behind schedule.

Controversy surrounding the plan only grew over time as setbacks and delays stalled the project and costs began to add up. Pollution concerns had been gradually laid to rest, but renewed criticism came from groups concerned for the ecosystem of the Swatara and its flora and fauna, including the very fish that had been touted as a future feature of the park.

By the late 1990s, these groups included the Environmental Protection Agency and the US Fish and Wildlife Service, which were particularly concerned for the acres of important wetlands that would be inundated by the reservoir. Environmental degradation was now seen now the chief issue with the project.

By the end of the century, the reservoir’s estimated cost had risen to $40 million.

A new century and the end of the dam

In 1994, Lebanon would gain a new water supply in the form of the Lebanon Reservoir, which is located just outside the county border near Pine Grove in Schuylkill County. The 125-foot Siegrist Dam tripled the water capacity of the High Bridge reservoir on the site to 1.2 billion gallons and became the new second surface water source fed into the City of Lebanon Authority’s system after the intake facility already on the Swatara.

Following a decade of nationwide dam unpopularity, as well as constant pressure from opponents, the idea of a dam appeared to be on its last legs. In April of 2000, after four decades of plans, meetings, and studies, the DCNR announced that the plans for the development of the reservoir were halted.

The Swatara State Park

Unlike the dam, the state park that would have surrounded it is today a reality, though it’s not exactly the same park that was shown off to the public back in 1969.

Five major areas were part of Goddard’s initial plans. These included Green Point Recreation Area (a day use area with a capacity of 5,300 people), Point Park Overnight Area (2,500 people and access from Route 443), Midway Overnight Area (camper and boating facilities for 2,800 people), Suedberg Recreation Area, and a fifth area with the potential for boat docks, camping, and even an airport.

Fishing was among the the biggest draws, but swimming, boating, and other “flat-water forms of recreation” were also accounted for on the reservoir, estimated to be around 1,400 feet wide on average and around 38 feet deep near the dam. Motorboats with up to 10 horsepower were to be permitted on the lake.

Early estimates made by Goddard placed the expected annual number of visitors to the completed park at around 1 million, a number that could have been made possible thanks to the proximity of Interstate 81. For comparison, attendance numbers in recent years have been around 150,000 or so.

Work on the park, which had remained undeveloped since 1987, began in 2011 and it was officially opened the following year.

Today, Swatara State Park is dam-free and likely to stay that way for the time being. Some would say that’s a good thing, and some wouldn’t. Concerns over water shortages in the future are still relevant, though any talk of a new dam project is likely to receive considerable opposition due to ecological, financial, and logistical concerns.

If there’s one lesson to be taken away from the story of the Swatara Dam, it’s that nobody can predict the future and the setbacks, progress, and problems it will bring. Perhaps this is not the last we’ve heard about a dam on the Swatara.

Read More: Historic Inwood Bridge off the Swatara, being readied for new placement

Want to learn more about the project and the Swatara Creek and State Park? Visit the Swatara Watershed Association’s webpage and the DCNR page for the park.

Questions about this story? Suggestions for a future LebTown article? Reach our newsroom using this contact form and we’ll do our best to get back to you.

Keep local news strong.

Cancel anytime.

Monthly Subscription

🌟 Annual Subscription

- Still no paywall!

- Fewer ads

- Exclusive events and emails

- All monthly benefits

- Most popular option

- Make a bigger impact

Already a member? Log in here to hide these messages

Strong communities need someone keeping an eye on local institutions. LebTown holds leaders accountable, reports on decisions affecting your taxes and schools, and ensures transparency at every level. Support this work with a monthly or annual membership, or make a one-time contribution. Cancel anytime.