This article is shared with LebTown by content partner Spotlight PA.

By Rebecca Moss of Spotlight PA

HARRISBURG — “I feel like I am a sinking ship right now.”

“Next month will be a year that they have been putting me through this.”

“I just need some help, I am about to be homeless.”

“Please help.”

The unemployed in Pennsylvania — pregnant people, parents unable to pay child support, nursing students, and adult children caring for disabled parents, among many others — have spent months over the last year waiting to receive benefits they are entitled to from the state Department of Labor and Industry, to little avail.

And depending whom you ask, some much-needed relief — or added suffering — is imminent.

This week, the state’s 60-year-old unemployment benefits computer system will temporarily go dark as officials roll out a massive upgrade to a new, cloud-based program. The project, nearly two decades in the making, is being hailed by the Wolf administration as the long-awaited fix to problems that have stymied state benefit claimants during the pandemic, and for years before it.

But technology experts and unemployment advocates are warning that the state’s decision to shift now, while so many Pennsylvanians are still relying on the benefits, is irresponsible. It could exacerbate existing problems as well as divert resources from helping those who are stuck in a backlog. People’s lives have already been disrupted by the Department of Labor and Industry’s missteps, advocates said, and the stakes are too high.

“It just introduces this immense new volume of problems into a system that is already overwhelmed with problems, and that is if it is working reasonably well,” said Sharon Dietrich, a lawyer with Community Legal Services in Philadelphia. “What if it doesn’t?”

The overhaul is the heart of a $35 million contract with Florida-based Geographic Solutions Inc., which is leading the project and will manage the new system. Residents will not be able to file new state unemployment claims from May 31 through June 7, and people with continuing claims will not be able to file from June 3 through June 7. The new system is to be up and running June 8.

William Trusky, the state’s deputy secretary for unemployment compensation programs, said he anticipates minimal benefit disruption but acknowledged, “There will be bumps in the road.”

“These projects aren’t easy,” said Trusky, noting that the last state to modernize at this scale was Florida in 2013, in a launch widely considered to be a huge failure. “It’s not easy to modernize, and it’s certainly not easy to modernize during a pandemic.”

‘I’m not fraudulent’

Fourteen months into the pandemic, as many as one million people in Pennsylvania may still be struggling to find work, according to the most recent job numbers, from April. Of that number, at least 212,600 are relying on state unemployment benefits, and an average of more than 22,000 new claims have been filed each week for months.

Dietrich and other lawyers and advocates said their inboxes are full of “absolutely heartbreaking” stories of people who need help, beyond what they have the resources to handle.

They also point out that GSI is already working with the state to distribute federal pandemic unemployment, through a system that has had its own problems.

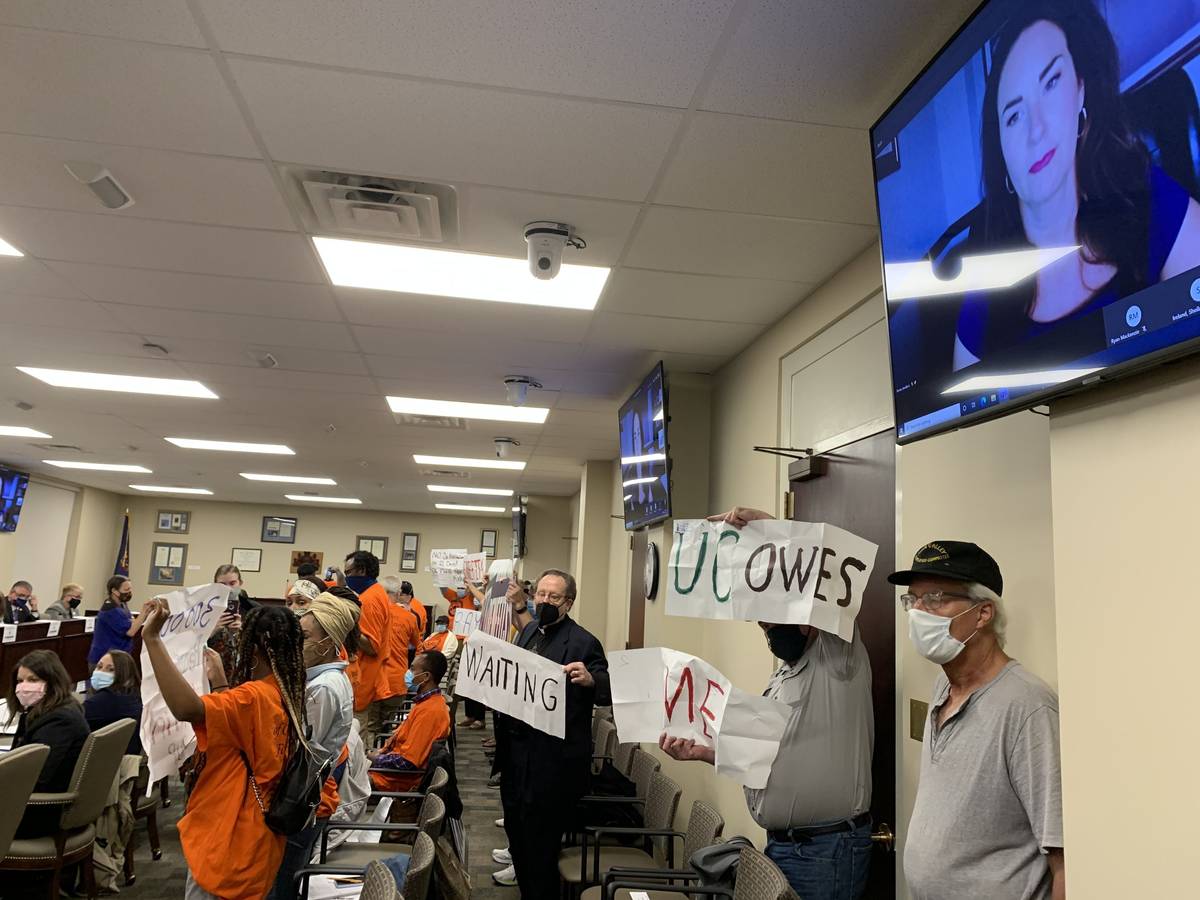

At a labor hearing at the state Capitol in Harrisburg on May 24, claimants held up signs reading “Pay Benefits Now” and “How Long Must People Wait!,” the words hand-drawn in bright markers. As state officials lauded the launch of its new system, workers presented letters to lawmakers and reporters showing they were approved for federal benefits in December but have never been paid.

GSI was awarded a separate, $4 million contract in 2020 to process federal benefits in Pennsylvania. Lawyers and advocates have brought complaints to the state about the contractor, which include cutting off at least 50% of benefits from people it accidentally overpaid, higher than what is legal in the state, and identification issues, with little state intervention. GSI technology has in the past been criticized in other states, including Louisiana and Tennessee.

Hundreds of thousands of claimants are also stuck in a backlog, waiting for their state and federal claims to be reviewed and for payments to arrive. State officials contend that more than 80% of the roughly 200,000 pending federal claims are fraudulent; there are also more than 100,000 state claims pending review.

But advocates counter that a combination of GSI’s technology and the department’s failings, such as inadequate staffing, leaves deserving and desperate people in limbo. They said some people have been mistakenly flagged as fraud, and others present at a recent legislative hearing said they had been hamstrung by identity verification investigations.

“I am not fraudulent,” said Adrienne Berry, 54, an independent contractor whose cleaning business temporarily dried up as a result of the pandemic and who needed to prioritize caring for her grandson.

Berry said she received three weeks of payments in 2019 before her claim stalled without explanation. While she recently started working again, she has not received any of the benefits she is owed for the weeks she went without assistance since December.

Because the new computer system will handle state unemployment claims, it will not address the issues faced by workers relying on federal pandemic benefits.

Michelle Griffith, a spokesperson for GSI, said the new system slated to go live in Pennsylvania has “been thoroughly tested and has been successfully operating in multiple states for a number of years,” while deferring questions to the state.

The state Department of Labor and Industry has faced an enormous wave of claims since March of last year, paying out $43.5 billion in various state and federal unemployment benefits over the last 14 months, handling 4.7 million calls, emails, and chat messages in that period.

Under such circumstances, few, if any, states haven’t experienced at least some pain with their unemployment systems. Even still, claimants in Pennsylvania have spent hours, often days, trying to get help from the department and its decades-old system.

Officials insist that it is necessary to launch the new system now, and when it goes live on June 8, claimants will see a crisp new portal that streamlines the ability to review their claims, communicate with caseworkers, upload documents, and more easily appeal denied applications.

“I understand change is scary,” acting Labor Secretary Jennifer Berrier said during a May 10 news conference. “However, we are ready — we cannot delay.”

Waldo Jaquith, a government technology expert who works at Georgetown University’s Beeck Center for Social Impact and Innovation, said the odds for success are “really gruesome.”

Timing aside, more than 87% of government technology upgrades face significant challenges or fail outright nationwide, according to the Standish Group, an international IT research group. Throughout history, these overhauls have been notorious for delays, excessive cost, or unusable code.

Jaquith said the state is using a “Big Bang” approach, by shutting down the old system entirely, which leaves little room for inevitable errors in between. Making technological improvements piece by piece has proven to be more successful, as well as prioritizing worker training so staff understands how to use new systems.

“One hundred percent of the time I advise against these things where you just flip a switch,” he said. “You are just setting yourselves up for trouble.”

‘Rubber bands and duct tape’

Pennsylvania’s efforts to modernize its system for handling unemployment compensation, tax programs, and numerous other unemployment services have been beset with failure, delays, waste, litigation, and false starts. Over 15 years, spanning three administrations, the promise of modernizing it and its services has already cost taxpayers at least $200 million.

The original mainframe was built by IBM in the 1960s, marking the start of the state’s long relationship with the tech company that ended with a dissolved contract in 2013, and a lawsuit filed in 2017 that is still pending. IBM built on an old but powerful mainframe computer, with large iron boxes that process millions of datasets at once, and green-screen terminals.

Because of its processing power, many states, the federal government, banks, airlines, and more still rely on this hardware.

For decades, there have been ongoing pushes by the federal government to outsource technology so as not to compete with private industry, and to keep pace with innovation. This philosophy has persisted despite significant evidence that outsourcing technical capacity is costing public agencies more money and depleting internal expertise.

In the early 2000s, the state Department of Labor and Industry decided to overhaul its existing technology, saying it was outdated, relied on a patchwork of legacy programs that can take days to process simple issues, and operated with coding language skills that are finite.

So, in 2005, it inked a four-year, $109.9 million contract with IBM that spanned 6,500 pages and laid out 1,500 “explicit business requirements.” IBM would integrate all the unemployment compensation technology systems, calculate payments and tax information seamlessly, transfer data from the old system, and provide an easy-to-use, internet-based interface.

These are known as waterfall projects, Jaquith said, because they present an extensive, top-down list of requirements laid out by a government agency and handed off to a developer.

By 2013, few of the requests had materialized. The project was $60 million over budget, nearly four years behind schedule, and still unusable, according to legal documents. Each time IBM failed to meet a deadline or deliver a project goal, Pennsylvania incrementally paid the company more.

Pennsylvania was not an outlier. As of 2016, roughly 77% of unemployment modernization projects nationwide had failed, were over budget and lacked critical requirements, or were still in progress, according to a recent report by the Century Foundation.

The state sued IBM in 2017, seeking to recoup the money and cost of maintaining the existing legacy system, accusing it of using the state as its “personal cash register,” according to the complaint.

The state wrote in 2017 that it “did not have the expertise or information to fully evaluate the project risks and perils of which IBM was aware.”

And part of that was because of the underinvestment in staff and technical resources over the years, said Gerald Rickabaugh, 63, who spent most of his career of more than 35 years working in IT for Labor and Industry before retiring in 2016. That year, the state laid off 32 IT staff, some with decades of experience.

Rickabaugh said IBM’s mainframe is more powerful and secure than the new, cloud-based GSI system.

“They love to blame everything on the mainframe system,” Rickabaugh said. “The mainframe is what held that place up. It worked fine.”

He said this included eight million claims processed during the Great Recession.

Since the onset of the pandemic, the Department of Labor and Industry has added hundreds of workers to help process more than six million federal and state claims, including more than 80 claims examiners and 250 contract workers to answer the phone, but has cited problems with retention and being able to train staff skilled enough to handle complex cases.

Still, there have been numerous issues. The mainframe system required batch uploads that could delay certain processing to occur the next day, and did not allow people to see updates in real time. State officials also contend that it’s not intuitive, it’s difficult to code new federal or state regulatory changes, and it does not readily allow claims examiners to see problems as they arise.

Berrier downplays the power and sophistication of the mainframe, saying it is “held together with rubber bands and duct tape.”

“Frankly, during this entire pandemic, we were basically crossing our fingers with our legacy mainframe system as we were making changes to it,” she said.

Another massive contract

The contract with GSI for the latest upgrade is more than 2,500 pages. The company’s technology is known as “off the shelf” or “plug and play,” meaning underlying software is adapted to the needs of the client rather than built from scratch.

But a Carnegie Mellon University study found that these systems had “very little success,” and the underlying assumptions about how to adapt the technology to a new environment lead to “virtually all our serious problems.”

There are also technical concerns: Advocates said a new password requirement could lock numerous people out of the system, and the state’s attempts to educate the public about how to use the new portal are not practical or helpful for most. It is relying on claimants to read a 45-page instruction manual posted on its site or attend an hour-long webinar.

Scott Andes, executive director of the Block Center for Technology and Society at Carnegie Mellon University, said too few governments prioritize the most important question when modernizing a system: Does the technology benefit the public?

“I don’t think we have seen that across the board,” Andes said.

State officials said they have done extensive internal testing of the new system, but because of the pandemic, as of mid-May, only five members of the public, five employers, and five legislative staffers had participated in trial runs.

“This particular project has been tested unlike any other IT project has been tested within the commonwealth,” Berrier said Friday. “We are fairly comfortable with saying we are not expecting a major failure.”

She said the state has a “pull in case of emergency switch” but added, “The likelihood of that happening is very, very slim.”

Deputy Secretary Trusky said the state will also launch with “all hands on deck” and have a “war room” for issues as they come up, alongside GSI staff.

At an advisory committee meeting for the new system on May 26, Saralinda Bauer, a consultant on the project with CSG Government Solutions Inc., said the overall status of the project continues to be “red.”

“This is, overall, a high-risk project,” she said. “That does not mean we cannot continue to go forward with ‘go live.’”

WHILE YOU’RE HERE… If you learned something from this story, pay it forward and become a member of Spotlight PA so someone else can in the future at spotlightpa.org/donate. Spotlight PA is funded by foundations and readers like you who are committed to accountability journalism that gets results.