This article is shared with LebTown by content partner Spotlight PA.

By Jaxon White of Spotlight PA

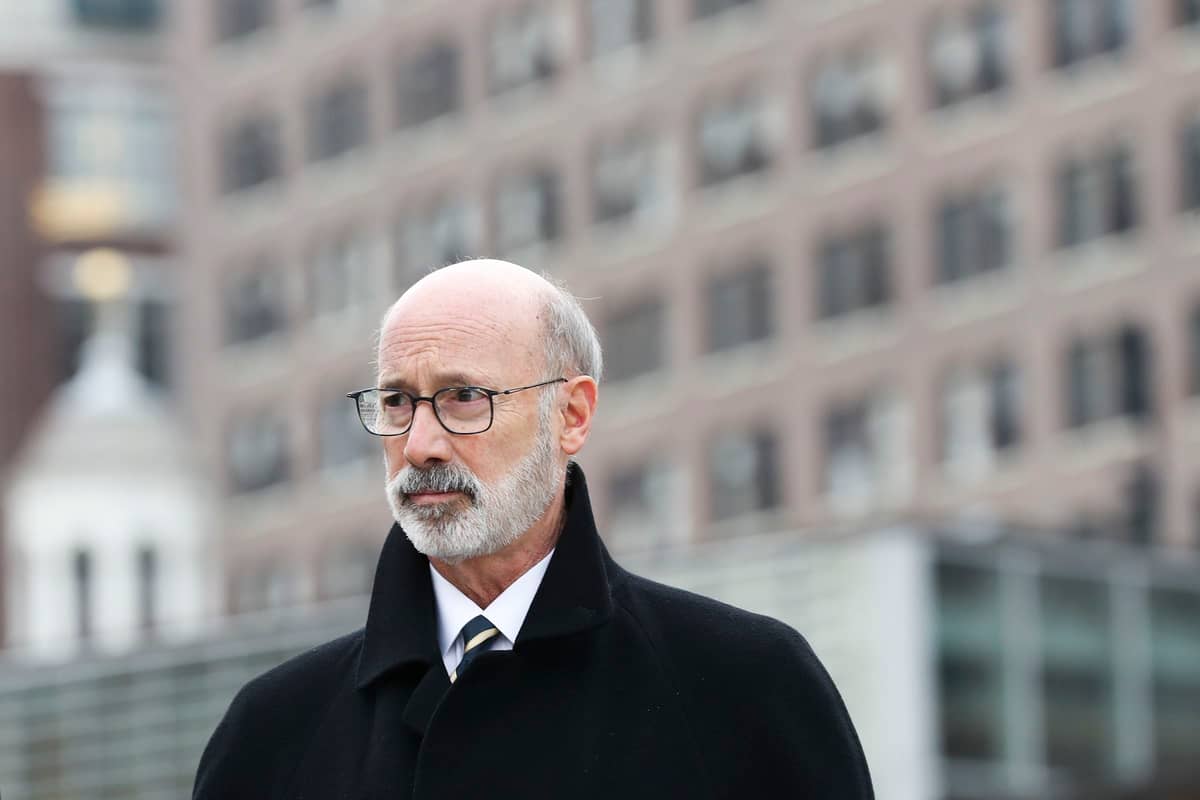

HARRISBURG — Gov. Tom Wolf is asking the Pennsylvania legislature to spend millions to raise a key reimbursement rate for skilled nursing homes in the state to help offset costs from proposed new regulations that would increase daily required care.

With the state’s June 30 budget deadline quickly approaching, the Democrat wants to appropriate $91.25 million to increase the amount of money skilled nursing homes receive for residents on Medicaid.

Roughly 11,000 long-term care residents in Pennsylvania have died since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, a toll that brought renewed attention to longstanding issues such as dangerously low staffing requirements and outdated regulations.

Groups including the Pennsylvania Health Care Association, which lobbies on behalf of long-term care providers in the state, say the state’s low Medicaid reimbursement rate is a major roadblock to providing higher levels of care. The current rate, they say, can leave nursing home facilities without funding to raise employee wages or buy supplies for patient care.

The association estimates that Wolf’s investment would raise the daily Medicaid reimbursement rate to about $210 per resident on average from the current $199.96 average rate. Neighboring states such as Ohio, Maryland, and New Jersey, have higher rates.

But while PHCA sees Wolf’s proposal as a welcome first step, the organization argues it’s not nearly enough. The trade group estimates the regulatory changes would require hiring 10,000 additional workers and spending $434 million more annually. That has led some to reject the plan as an unfunded mandate.

According to the Pennsylvania Department of Health, there are 683 nursing homes in the state serving about 80,000 total residents. That number is expected to rise in the coming years as the state’s population over the age of 65 grows. According to PHCA, about 66% of residents living in nursing homes across the state have their stay paid for by Medicaid. Medicare accounts for an additional 13%.

There does appear to be agreement among legislators that more investment is needed, but how to do so is still being debated. If funding for nursing homes remains as is, advocacy networks, experts, and nurses on the ground fear facilities may be ill-equipped to support the aging population.

“We’ve come to a place where we either need to make an investment in long-term care in this year’s state budget, or the entire system could collapse,” said Zach Shamberg, president and CEO of Pennsylvania Health Care Association. “That would be disastrous for our older population.”

Why do reimbursements matter?

With the way that Medicaid and Medicare funds are distributed, many nursing home facilities seek to take in Medicare-funded patients rather than Medicaid-funded ones.

“We’ve decided in this country not to cover long-stay nursing home care under Medicare,” said David Grabowski, a professor of health care policy at Harvard Medical School. “So it’s really the one major piece of services that are pushed today over to Medicaid.”

Medicare is a federal insurance program that typically covers short-stay patients, such as patients in physical therapy or post-surgery care.

Medicaid is a state-run assistance program that — following guidelines from the federal government — supports low-income people and typically covers long-stay patients. The reimbursement rate is what each nursing home is paid on behalf of the qualified patient by the state government.

According to Grabowski, the low Medicaid reimbursement in Pennsylvania encourages nursing homes to seek out Medicare patients planning on short stays rather than accepting Medicaid patients who will require long stays.

This dynamic, he continued, makes the federal government “a very generous payer,” and that windfall allows care facilities to typically hit double-digit margins on short-stay patients. Meanwhile, Medicaid patients usually result in negative margins for facilities, he said, causing a gap between the cost of care for residents and the amount of state funding.

According to a February study conducted for LeadingAge PA, a trade association that represents about 380 providers in the state who serve older adults, the daily gap between what nursing homes received for Medicaid residents versus what they spent was $86.26 per resident on average.

Grabowski said increasing the Medicaid reimbursement rate could relieve some of the problems. Lobbyists and advocates for the industry in Pennsylvania are asking for a $294 million investment, rather than Wolf’s proposed $91.25 million.

Grabowski argues any investment in the industry should also involve some form of accountability to make sure the funds improve the quality and are not misused.

“I do think we’re going to have to rethink what it means to both live and work at a nursing home,” Grabowski said. “Because the current economic model is definitely broken.”

More money, more oversight

Wolf’s $91.25 million pitch comes with proposed regulations that would require nursing homes to provide more hours of direct care to residents.

Spokespersons for state House and Senate Republicans confirmed the caucuses will consider the proposal and continue to make investments in nursing homes, but did not provide details.

In 2020, Spotlight PA reported on long-criticized staffing and training regulations that were exposed by the pandemic. Shamberg said that PHCA has found that, on top of rising costs nationwide, nursing homes face these same issues today.

Since the start of the pandemic, the state has earmarked nearly $500 million to nursing homes through Acts 24 of 2020 and 2021. These funds were intended to help ease the burden of additional COVID-19-related costs. But as one-time infusions, PHCA said the money did not address the Medicaid reimbursement rate gap, and therefore did not increase staffing.

Karen Hipple, a licensed practical nurse at Oil City Healthcare and Rehabilitation Center in Venango County, said staffing ratios are too high — with one certified nursing assistant caring for 20 to 30 patients, in facilities she’s worked in and visited. She said that staffing increases need to be the top priority, which requires more funding.

Hipple blames the shortage on the low wages that many workers face in nursing homes. According to data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, the average pay for a nurse assistant is $16.44 an hour.

WHILE YOU’RE HERE… If you learned something from this story, pay it forward and become a member of Spotlight PA so someone else can in the future at spotlightpa.org/donate. Spotlight PA is funded by foundations and readers like you who are committed to accountability journalism that gets results.