Few of us relish the gas that can occur when our digestive systems go awry, but at the City of Lebanon Authority’s wastewater treatment plant, more gas is good news.

That’s because the more gas that is produced during wastewater treatment, the more efficiently treatment processes are working. A drop in gas production signals an issue—and that’s what happened at the wastewater treatment plant in June.

What happens at a wastewater treatment plant?

“We make dirty water clean,” says Frank DiScuillo, wastewater systems director with the City of Lebanon Authority.

That’s the short version of what’s involved in treating wastewater—that is, anything that goes down a drain in any building in the Authority’s service area.

It is a process that is simultaneously simple and complex.

It is simple because it is a natural process relying on bacteria for decomposition. It is complex because the natural processes are accelerated and concentrated so that the water can be cleaned for reuse in a short time.

Initially, liquids are separated from solids such as food, fecal matter, paper products and chemicals (DiScuillo said he once found three $20 bills that had entered the wastewater plant).

Then through a system of settling, chemicals or treatment with different bacteria, pollutants such as carbon, nitrates/nitrites and ammonia are removed or converted into solids and gas which can be separated from the water.

Once the cleaned water has met federal standards, it leaves the plant and is discharged into the Quittapahilla Creek.

The remaining organic solids–byproducts of removing pollutants and chemically-treated phosphorous so it clumps together–are pumped to the digesters along with the multitudes of bacteria that have fed on the now removed pollutants.

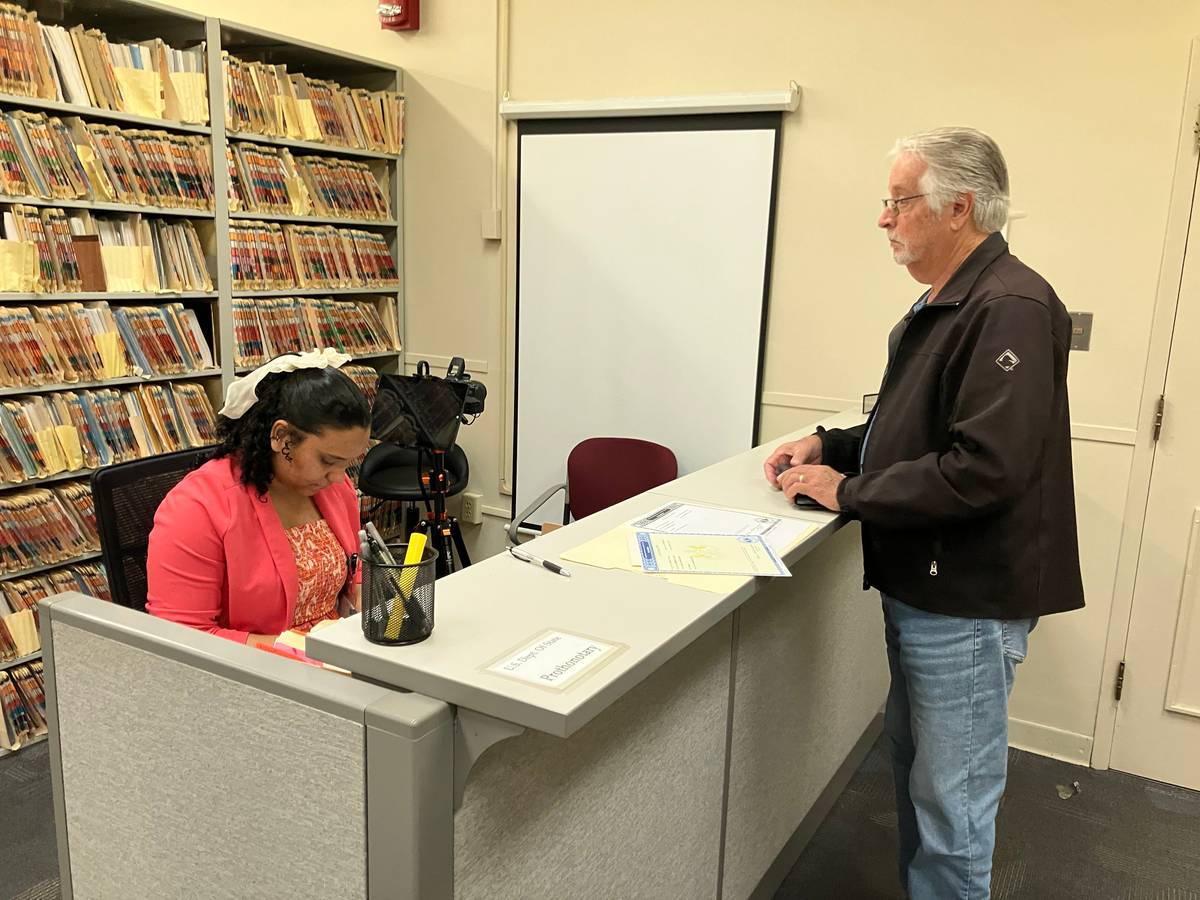

Twice a week the Authority’s lab samples the biosolids in the digesters and checks total solids, alkalinity and volatile acids, said Cora Shenk, compliance and lab manager with the Authority. Those analyses, combined with monitoring of gas production, are the key parameters in ensuring treatment processes are working efficiently.

Average daily gas production dropped from 130,000 cubic feet to 53,000 cubic feet, said Frank DiScuillo, the Authority’s wastewater systems director.

The cause: “Some of those bacteria in our system became less active,” DiScuillo said.

Just as we depend upon bacteria to break down food in our digestive systems, so do the wastewater treatment plant’s two digesters, which function similarly to our stomachs. Critical for waste treatment are methanogens, which digest acids and, as part of that digestive process, produce gas.

“The temperature in our digesters got up to 108 degrees, and some key bacteria in our system prefer temps in the mid-90s,” DiScuillo said.

When the population of methanogens fell, not only did gas production drop, but the breakdown of waste slowed as well.

DiScuillo reached out to Michael Gerardi, a Williamsport, Pa.-based microbiologist who consults with wastewater treatment plants when they are having problems. His recommendation: Add 5 gallons of fresh cow manure—“the fresher, the better,” Gerardi said—for every 100,000 gallons of biosolids in the digesters.

So, on July 7, treatment plant operators added 5,000 gallons of fresh manure collected from a dairy farm in Schaefferstown. By the end of that week, daily gas production had climbed to 76,000 cubic feet, said Cora Shenk, compliance and lab manager with the Authority.

“We are now producing more gas than ever before,” DiScuillo told Authority board members at their meeting Monday.

That’s good news as the authority uses that methane not only to heat the digesters but also to make a nutrient-rich fertilizer approved by the state Department of Environmental Protection for use in gardens, landscaping and agricultural fields, DiScuillo said.

Additionally, a pilot project with Reading-based DURYEA Technologies to install 10 prototype engines will convert more of the digester gas to electricity for use at the Authority, DiScuillo said.

The first two of those engines should be installed within the next month, DiScuillo said at Monday’s Authority meeting.

While the immediate indigestion problem has been solved, DiScuillo isn’t ready to close the door on future infusions of manure.

“When we have more beneficial reuse for our digester gas, we may explore the options of adding more cow manure to our digesters regularly,” DiScuillo said.

Questions about this story? Suggestions for a future LebTown article? Reach our newsroom using this contact form and we’ll do our best to get back to you.

Become a LebTown member.

Cancel anytime.

Monthly Subscription

🌟 Annual Subscription

- Still no paywall!

- Fewer ads

- Exclusive events and emails

- All monthly benefits

- Most popular option

- Make a bigger impact

Already a member? Log in here to hide these messages

Free local news isn’t cheap. If you value the coverage LebTown provides, help us make it sustainable. You can unlock more reporting for the community by joining as a monthly or annual member, or supporting our work with a one-time contribution. Cancel anytime.