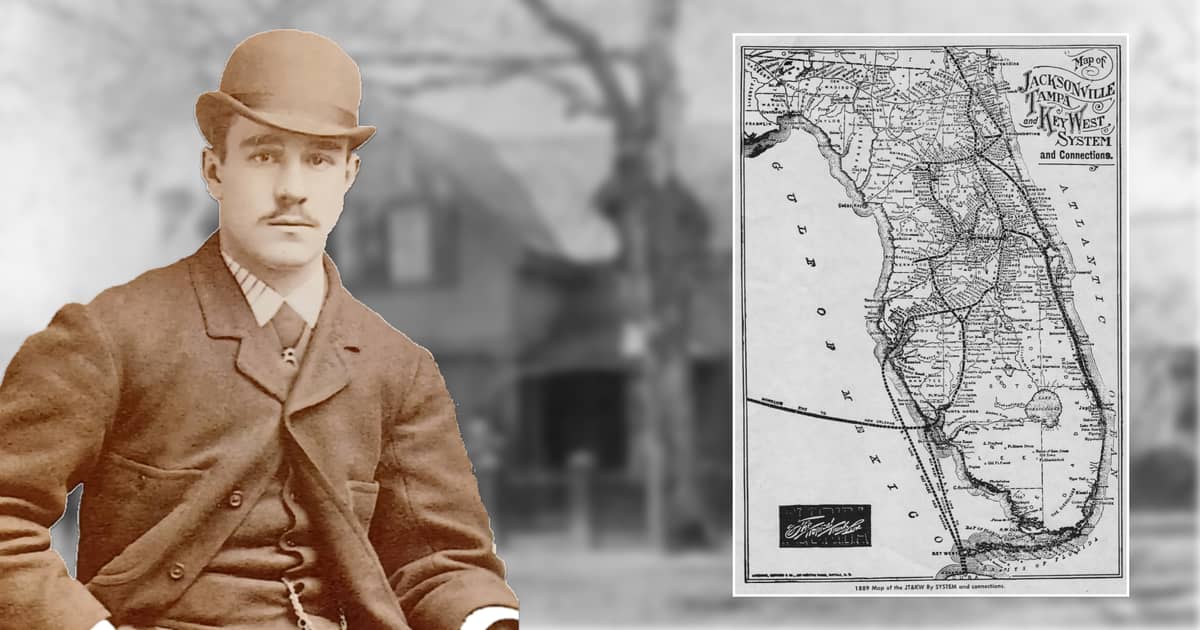

‘Tis the season … when snowbirds fly south to Florida. This is the story of one man, Robert H. Coleman, who made the journey.

Part 1 of this series on the curious life and legacy of Robert H. Coleman examined the circumstances that lured him to risk his vast fortune in Florida.

Part 2 looked at Robert H. Coleman’s upbringing and education, and the early passions that came to play a huge role in his life and career.

Part 3 explored the full scope of all Coleman’s activities in Lebanon County during his “busy decade.”

Part 4 looked at how Coleman’s Florida exploits led to his undoing.

In this installment, learn how Coleman found sanctuary in Saranac Lake.

In the turmoil leading up to his demise in 1893, Robert H. Coleman left Lebanon with his family and headed to Saranac Lake in New York. “Sanctuary” speaks both to finding a place to suffer his humiliation, as well as to find help for the tuberculosis, or consumption, that ailed both him and Edith.

Why did he go to Saranac Lake? Why not go south, to the Georgia homestead? Too close to painful memories in Florida? Was it to be close to his sister Anne in Hyde Park, where his mother spent her final days?

The choice of the Adirondacks was not all that surprising. Coleman’s mentor Artemas Wilhelm had been to the nearby springs of Saratoga in 1879 for health reasons. With the disease accounting for one in seven deaths in the United States and Europe in the late 19th century, Saranac Lake was well-known as a treatment center.

Dr. Robert Koch discovered the tuberculosis bacterium in 1882. Dr. Edward Livingston Trudeau, himself suffering the disease and a visitor to Saranac Lake since the 1870s, opened his sanatorium in Saranac Lake in 1884. In 1903 he signed Edith’s death certificate, with the cause of death “pulmonary tuberculosis (had the disease when I first saw her, 1895).” Presidents and other famous people found help at the institute and Coleman was likely one of its benefactors.

The Trudeau Institute continues to operate today, researching infectious diseases such as COVID-19.

The details as to when Robert and Edith contracted the illness are unclear. There is some conjecture that the diagnosis of “TB” was often attributed to a wider range of respiratory illnesses. Lebanon County’s questionable air quality – with wood stoves, the ashes of iron furnaces and coal-burning engines – was likely detrimental to many. Furthermore, Robert was known for his continuous smoking of cigars.

The prescribed treatment was as much fresh air as possible. Rather than build a large sanatorium to house patients in close quarters, Trudeau’s concept was distributing the patients among “cure cottages.” Patients would rest outdoors in beds and chairs for eight hours a day on the front porches of their cottage.

Over time 900 cure cottages were erected. It was easier for Trudeau to convince his wealthy friends to sponsor the cost of an individual cottage, rather than joining a faceless pool of donors for a large facility. Others seeking treatment found it more cost-effective to build their own cottage rather than rent a room for a long period.

The Coleman cure cottage was designed by William L. Coulter of the Renwick, Aspinwall & Renwick architectural firm, for whom Coleman is described as his “first famous client.” Coulter went on to design many of the distinctive rustic camps around Saranac Lake and Lake Placid.

The drawings for the cottage are labelled “House for Mrs. Edith E. Coleman.” The floor plan included a northwest wing for kitchen, laundry, and servants’ quarters. The cottage was on a rise at 33 Church St., between Church and River streets above Lake Flower, on the Saranac River.

St. Bernard’s Roman Catholic school would be built a few years later on the property to the west on River Street. The house was torn down around 1934 when St. Bernard’s bought the property, which is now a school playground. Another of Robert H. Coleman’s homes ceased to exist.

The Colemans were members of St. Luke’s Episcopal Church on Main Street. Trudeau had helped establish the church in the 1870s, serving as fundraiser, treasurer and church warden for 38 years. It is possible that Coleman’s Episcopal roots also played a role in connecting him to Trudeau and Saranac Lake.

The photos of the church compare to that of the original Lebanon’s St. Luke’s Episcopal Church. Dr. Terry Heisey of the present-day church in Lebanon agreed that they are both typical “carpenter gothic” churches like hundreds of others of the time.

Comfort in the mountains

It may not have been humiliation that sent Robert H. Coleman to the north country. Rather than dive back into his economic conquests, he may have finally heeded the voices of his past mentors and the fresh memory of his mother’s death the previous year. Consistent with his giving and generous personality, the hard lesson of default may have convinced him to turn to a quieter life and attend to those closest to him.

Coleman’s motivation seems two-fold during this period: First, providing a comfortable place for Edith to convalesce; secondly, providing a suitable environment for their children.

The Coleman children enjoyed a comfortable life growing up in Saranac Lake. Many of the photos in Robert’s album are of the family activities like tennis matches and boating. The spacious house featured a billiard room and other comforts.

Three sons would serve in the military in Europe during World War I. One son later went on to work on the development of the Panama Canal. Daughter Anne Caroline Coleman would be married at their Episcopal church in 1912.

A Lonely Man?

Tragedy continued to follow Robert. He again suffered the loss of a spouse, as Edith died in 1903. Son Ralph died in 1910 of suicide, having dropped out of Yale College. And his oldest son Robert died in France of pneumonia while serving in the armed forces.

Despite tragedy Robert H. Coleman remained active. He continued to enjoy favorable press after retiring to Saranac Lake. He enjoyed visits with various well-to-do friends, including a retreat to the Ampersand Hotel in 1896 with the Anne Rogers family and other socialites.

Saranac Lake organized the Pontiac Club to promote outdoor sports, for which Robert served as vice president.

Nor had he been forgotten here in Lebanon County. In 1913 a group of businessmen from Lebanon and Cornwall made the trip to Saranac Lake to spend 10 days with Coleman. And in 1920 he was elected honorary member of the vestry of St. Luke’s Episcopal Church of Lebanon.

Robert H. Coleman, cigar aficionado

In Richard Noble’s account “A Touch of Time,” Robert was frequently seen pacing the front porch of his cottage, smoking an ever-present cigar. He would be “going for a walk,” as Coleman described it, though never leaving his porch.

But he did get out – for a while he tried running a cigar store in Saranac Lake, featuring fine Cuban cigars. The business fared no better than his railroad ventures and he let it go.

Robert H. Coleman, bird man

Coleman was a bird watcher, having taken considerable time to wander the woods of the Adirondacks. The 1921 “A History of the Adirondacks” by Alfred L. Donaldson contains in Appendix J a “List of Adirondack Birds – Compiled by Robert H. Coleman,” who is credited with providing a list of birds “easily found and recognized” in the mountains. The list spans five pages, enumerating 153 “residents” by common and Latin names, including warblers, vireos, thrushes, woodpeckers, owls, and others.

Bird-watching was not a hobby newly acquired during his isolation. In early 1879 an acquaintance from Chicago, whom he met briefly on a train enroute to Savannah, corresponded with him regarding a particular bird, and recommending a book “Birds of North America” by Elliott Coues (Boston, 1877), $7.50. This treatise probably inspired his own efforts in 1921.

A number of ornithology books and stuffed birds are mentioned in his last will and testament.

Robert Coleman, baseball man

He also had a wonderful opportunity to nourish his passion for baseball. Previously had been his years at Trinity and then organizing “railroad teams” in Cornwall, himself at first base. Directly across the street from his Saranac Lake cottage (in the Santonani apartment complex, established 1914) resided baseball great Christy Mathewson, who had pitched 17 seasons for the New York Giants.

Mathewson contracted tuberculosis after working with chemical warfare agents in World War I and spent much of the rest of his life in Saranac Lake from 1919 until his death in 1925. Another common bond between the two men, Mathewson was known for his devout Christian faith, refusing to play ball on Sundays.

One can imagine that baseballer Robert Coleman enjoyed his visits with Christy Mathewson.

Finally, Robert H. Coleman, train man

He may have kept his finger on the pulse of another old passion, trains. He could not help but notice the new rail station in Saranac Lake, built in 1892. Its architecture is reminiscent of his own Cornwall & Lebanon station in Cornwall.

His photo album provides no evidence of his travels. Train travel may have been his preferred mode of transportation, although automobiles were possible. According to all reports he never returned to visit Cornwall or Lebanon, but he did visit his sister in Hyde Park routinely.

In 1903 he had escorted Edith’s casket by train as far as New York, not strong enough to tolerate the full journey (according to Richard Noble, citing the Lebanon Daily News).

In late 1929 being in ill-health, Robert began staying with his sister Anne Rogers, herself widowed when her husband Archie died the previous year. Robert would survive tuberculosis but died of stomach cancer at age 73. His final train ride followed his death March 15, 1930, his casket being transported to Laurel Hill Cemetery, Philadelphia.

Robert H. Coleman, his legacy

It remains a challenge to understand the two versions of Robert H. Coleman in that decade prior to 1893. At times he was in two places at once, mentally if not physically, saddled with the cares of both. His life in Cornwall and Lebanon seemed wildly productive and effortless. One thousand miles away, Florida became for him a swamp of cares, mired in the details of integrating multiple small railroads, leveraging financial instruments, and acquiring a million acres or more of land for some unknown and future plan.

In the end, his legacy seems neither the iron industry, his passion for railroads nor a grateful Lebanon, but simply a life well-lived. He enjoyed seeing his children grow up; he knew the comfort of a life-long relationship with a doting sister who understood him and loved him until the very end. He had soaked in the solitude of the Adirondack Mountains. He had suffered tragedy again and again, but without regret, knowing that he had played the game. He had lost but picked himself up to play another day.

Reflection

The holiday season just behind us, and with scenes of Bedford Falls-turned-Pottersville in Jimmy Stewart’s “It’s a Wonderful Life (Frank Capra, 1946)” still playing in our heads, imagine how Lebanon County would have fared if things had gone differently in 1883.

That was the year, early in Robert H. Coleman’s Florida business venture that he was doubting himself.

It was a watershed moment, but the angel would not earn his wings. Cautious voices urged him back to safety, but he jumped off that bridge anyway. What if he hadn’t?

The many families of Coleman’s bank would not have lost their savings.

Lebanon would be a much larger and more prosperous city, with a history in the steel industry that rivals Pittsburgh. Coleman Stadium would be home to the Steelers.

There might still be a railroad passing through Cornwall and Mount Gretna. Though hard to imagine it being any better, Mount Gretna would not be the same. Our gain would have been Saranac Lake’s loss.

Cornwall’s great mansion would still stand in the center of the borough, inhabited by members of the Coleman family for the last 135 years. Coleman wealth would prosper this county in unforeseen ways.

With the help of William H. Barnum and his own wealth and personal charisma, Robert H. Coleman might have vaulted into national politics, even serving as president of the United States at the dawn of the 20th century.

Dedicated to Linda and our children.

Credits for this series:

The John and Margery Feitig collection at the Cornwall Iron Furnace

Insights from author James Polczynski; local historian Michael Trump; Richard E. Noble, author of “A Touch of Time“; Dr. Terry Heisey Principal Organist and Director of Music at Saint Luke’s Episcopal Church; Michael Emery, Site Administrator of Cornwall Iron Furnace.

Read Part 4 of Robert H. Coleman, Florida Man, here.

Read Part 3 of Robert H. Coleman, Florida Man, here.

Read Part 2 of Robert H. Coleman, Florida Man, here.

Read Part 1 of Robert H. Coleman, Florida Man, here.

Questions about this story? Suggestions for a future LebTown article? Reach our newsroom using this contact form and we’ll do our best to get back to you.

Keep local news strong.

Cancel anytime.

Monthly Subscription

🌟 Annual Subscription

- Still no paywall!

- Fewer ads

- Exclusive events and emails

- All monthly benefits

- Most popular option

- Make a bigger impact

Already a member? Log in here to hide these messages

Trustworthy local news is built on facts. As Lebanon County’s independent news source, LebTown is committed to providing timely, accurate, fact-based coverage that matters to you. Support our mission with a monthly or annual membership, or make a one-time contribution. Cancel anytime.