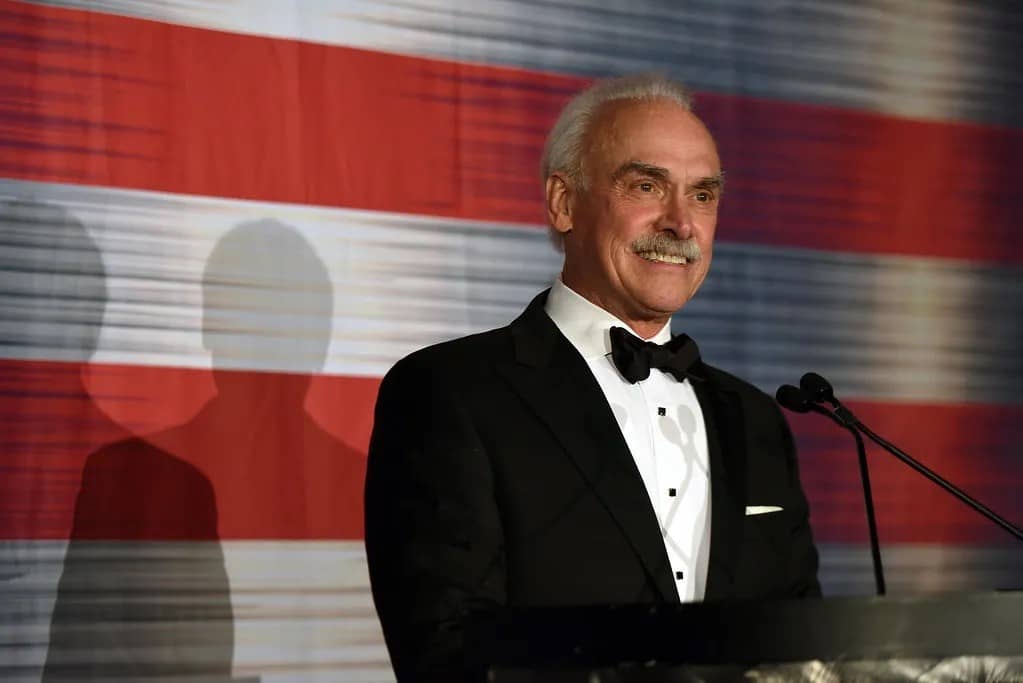

Rocky Bleier has led a unique life.

His high school football team went undefeated all four years and was top ranked in the state of Wisconsin.

He won a national collegiate football title as a running back at Notre Dame.

He survived potential career-ending injuries while serving his country during the Vietnam War and became a decorated veteran for his service.

And he played on one of pro football’s most dominant sports franchises of the 1970s as a running back on the Pittsburgh Steelers, a team that won four Super Bowl titles during his career.

Bleier believes his achievements were made possible thanks to a support system that helped guide him throughout life’s journey.

He will extoll the importance of individuals, especially older citizens, having support systems during a presentation to celebrate Cornwall Manor’s 75th Anniversary and honoring all veterans who have served their nation.

Bleier’s presentation begins at 7 p.m. Thursday, May 23, at Good Shepherd United Methodist Church on Quentin Road.

Read More: Gridiron star, Vietnam veteran will speak at Cornwall Manor 75th anniversary event

“In this case specifically, these are my people,” said 78-year-old Bleier. “I say that tongue-in-cheek, but independent living, community living, health care, we all get to that point in our lives. Probably the biggest thing about my message that I try to get across is, ultimately, what we have to understand and come to terms with is that no man is an island.

“We didn’t get to where we are today by ourselves. You get here because of someone – a parent, a teacher, a coach or a drill sergeant.”

Those support systems certainly influenced his life and our own “supporters” should be influential force in our individual lives as well.

“You got here because someone took an interest, you got here because someone kicked you in the rear end, showed you what to do and not to do. Our lives are molded in that area,” said Bleier. “So those who have touched our lives over that period of time get us into the direction that we’re going (in life).”

Bleier grew up in Appletown, Wisconsin, an avid Green Bay Packers fan. Like many boys, he played football and, because of his Catholic faith, attended a newly-opened Catholic high school in his hometown. His experiences there helped shape his life off and especially on the field.

“In my high school career, I never lost a football game,” said Bleier. “We were the No. 1 ranked team in the state of Wisconsin. So, you go, ‘Why did that happen?’ You happen to be with the right people at the right time. Because of that success, I got a scholarship to go to the University of Notre Dame and continue my education.”

A collegiate football rule change in 1964 concerning player substitutions, as well as the hiring of head coach Ara Parsghian — whose success would make him a legend in the college ranks — were also fortuitous developments for Bleier.

The specific ruling concerning substitutions led to lineup revisions for the Fighting Irish and an opportunity for Bleier to play.

“So I got an opportunity to play and by my junior year, we won a national championship and I became captain my senior year,” said Bleier. “We had successes and Ara turned the program around. We lost five games in a four-year period. Notre Dame is now back on the map and we get recognized. So, we get recognized as a team and because of that, I get drafted by the Pittsburgh Steelers.”

It’s hard to tell what trajectory Bleier’s pro football career would have taken if it were not for the Vietnam War.

After he was drafted in 1968 in the 16th round by the Steelers — following ACL surgery his senior year in college after a knee injury in the next-to-last game — Bleier said he was under the impression that being a football player meant he’d probably be drafted into the Reserves or National Guard.

“If I make the team, my assumption is that they would get you into the Reserve or the National Guard to fulfill that responsibility to the country that you had during that period in time,” said Bleir. “Why did I believe that? Growing up in Appleton, they told stories about Green Bay Packer players who did that to fulfill their (national) responsibilities. So that was a thought in the back of my mind.”

He never dreamt that he would be sent halfway around the world to fight in a war that, by the late 1960s, was becoming more controversial in the minds of the American public. But that’s exactly what happened after an attempt by Steeler team personnel failed to keep him out of the draft.

“I went down to the Steelers office and asked about taking care of this and they said they were having some problems, the congressman who would take care of it did not get re-elected,” said Bleier. “So I went on living my life.”

Then one day several months later, he received a letter in the mail.

“An equipment guy said, ‘Hey, Bleier, there’s a letter over here for you.’ I opened it up and it said, ‘Greetings. We’d like to inform you that you’ve been inducted into the armed services of your country.’ It was my draft notification to report the next morning at 8 a.m. to be inducted into the armed services. It was supposed to be there a week ahead of time, but it was post-dated and I got it the day before,” recalled Bleier.

Drafted Dec. 4, 1968, Bleier was in Vietnam by the next May. On May 20, while fighting with his fellow soldiers in Hiep Duc, he was wounded in the left thigh by a rifle bullet when his platoon encountered the enemy in a dry rice paddy field after walking out a wooded area.

While on the ground with his first wound, a hand grenade hit off the back of his commanding officer and rolled between Bleier’s legs. Bleier said he tried to escape, but the grenade exploded, sending shrapnel into his lower right leg and severely damaging his right foot in the blast. He would later be awarded the Bronze Star and Purple Heart.

Recuperating a few days in a field hospital in Da Nang before being sent to Tokyo, Bleier felt emotions that anyone in the same situation would experience.

“I had a morphine drip, an IV going into my body, and all of those thoughts that you have or people have of, ‘Why me? What’s going to happen with the rest of my life? What is my future going to be like? How bad are my injuries?’” he said.

An encounter with a fellow soldier — whose wounds were much more severe than his — gave Bleier some perspective on his situation.

“Across from me there was a young soldier, who was going to be a triple amputee, he had lost his left arm and both legs,” said Bleier. “Every day I watched him grab his trapeze that hung over his bed and helped him swing his torso into his wheelchair as the aides came to take him to therapy. He stopped at every bed in the ward. Honest to God I remember him saying, ‘Hey, how ya doin? I have to tell you, you are looking better today than you did yesterday. When you got here yesterday, let’s be honest, you looked like shit.’”

The positivity from this one person — who was a much-needed support system at that point in Bleier’s life — didn’t end there.

“Listen, we’ve got good docs here, they’ll take care of you and I’ll see you in the real world one of these days,” he recalled. “And I thought, ‘Wow, if anyone would be embittered, it would be that young soldier who lived with those atrocities that happened thousands of miles away.’ Yet he chose to have a positive attitude and make a difference. And I thought, ‘Wow, if he can have an attitude like that, what about me? I am going to walk someday.’”

During his stay in a Tokyo hospital, one person in a long line of supporters reached out to him in an innocuous but life-changing way. He received correspondence from Steelers team owner Art Rooney just days after a doctor told him he’d lead a normal life but would never return to the gridiron to play football.

“As my authority figure, [the doctor] just sucked that hope right out of me, “ Bleier said of the physician who chuckled when asked if he would ever play football again.

“Two days later, I got a postcard in the mail — a simple postcard that had two lines on it, and it said this: ‘Rock, Team’s not doing well. We need you, Art Rooney,’” said Bleier. “And you go, ‘Wow, somebody needed me.’ No, they didn’t need you, but somebody just took the time to care. And I tell people that being the family that they were then and are today, that’s the kind of impact they have on their players. They have empathy and feeling and are able to take care of their players.”

After he was discharged, Bleier was determined to return to the field. He made the development squad and the Steelers were patient, giving him several years to regain his former strength.

“In 1972, I was the leading ground gainer in the exhibition season, but didn’t carry the ball the whole year and only played special teams,” said Bleier. “In 1973, I was the leading ground gainer in the exhibition season, and I carried the ball one time during the regular season. After the 1973 season I figured my career wasn’t going anyplace. I felt my life was going in another direction.”

Bleier was in Chicago when he received a call from fellow teammate and captain Andy Russell that would prove to be another poignant moment of support in his life. He said he tells this story because it demonstrates how important having a support system is.

“He told me, ‘You can’t quit. If you do, you’ve already made the decision for the coaching staff. Do you like them well enough to make decisions for them?’” said Bleier about that conversation. “‘If this (play football) is what you want to do, you come back and make them make a decision. You back them into a corner, you give them every reason to keep you or release you, but you don’t cut yourself.’ Maybe it was just the arm twisting I needed because I went back.”

Bleier’s biggest individual achievement as a Steeler is when he and fellow running back Franco Harris rushed for over 1,000 yards in 1976, the second time in the history of the NFL that two players from the same team reached that remarkable achievement. (Four Super Bowl titles isn’t a bad accomplishment, either.)

Asked what his greatest achievement is in a lifetime of notable moments, Bleier hesitates a beat to contemplate the question and answers with as much conviction and love that any one person can make about the people that matter the most.

I say this in all honesty, and it’s true in all people, and it is the ability to have a family,” said Bleier. “Having four kids, seeing them and being able to raise them and see them grow. Having families of their own and becoming the people that they are is very rewarding to be able to see that. To have some kind of importance in the outcome of their lives and for the betterment of those lives.”

Which, for Bleier, was made possible by his life-long support system.

“Whether it was in the rice paddies of Vietnam or on the football field, it’s all about the people that support you or save your life,” said Bleier. “Being able to make an impact on your own is to see that through the lives of your kids and the kind of impact you had on their lives and who you hope they become. I just have to say that.”

If you go: $30 per person, doors open at 6 p.m., presentation begins at 7 p.m. Open seating in Good Shepherd United Methodist Church, 1500 Quentin Road, Lebanon.

Meet & Greet Reception: $100/person, Cornwall Manor’s Freeman Auditorium, 4 p.m. (Limited to 50 attendees.) Meet Rocky at a reception with light refreshments, photo opportunity and ticket to the program at Good Shepherd UMC.

Proceeds benefit 75th anniversary technology and transportation enhancements for residents.

To pay by check contact Tracy in the Cornwall Manor Advancement Office at

ttelesha@cornwallmanor.org or 717-675-1511

All sales are final. No refunds.

Questions about this story? Suggestions for a future LebTown article? Reach our newsroom using this contact form and we’ll do our best to get back to you.

Keep local news strong.

Cancel anytime.

Monthly Subscription

🌟 Annual Subscription

- Still no paywall!

- Fewer ads

- Exclusive events and emails

- All monthly benefits

- Most popular option

- Make a bigger impact

Already a member? Log in here to hide these messages

While other local news outlets are shrinking, LebTown is growing. Help us continue expanding our coverage of Lebanon County with a monthly or annual membership, or support our work with a one-time contribution. Every dollar goes directly toward local reporting. Cancel anytime.