Until the 1950s, much of Lebanon County’s trash was disposed of in open trenches, ravines, and abandoned quarries where it was simply left to rot. Fires were frequent, disease-carrying rodents were common, and streams and groundwater were contaminated by what is now known as leachate.

Recognizing these problems, county and municipal officials sought a way to close the 16 to 18 open-air dumps in operation. They settled on a new way to handle waste — namely, the “sanitary landfill method.” In short, the method involved flattening or compressing the waste, covering it with soil, and repeating this in layers.

The Greater Lebanon Refuse Authority was formed in 1959 and entered into a lease-purchase contract for an existing dumping area on 65 acres in North Annville Township. In April of that year, GLRA accepted the first loads of waste from nine member municipalities.

Read More: Trash talk: A bird’s eye view of the Greater Lebanon Refuse Authority

Less than 10 years later, GLRA faced two problems: running out of space and garbage juice, or leachate, oozing out of the ground and into a nearby unnamed stream. The first problem was solved by the purchase of a 137-acre farm that was developed into another landfill.

The leachate problem persisted. One suggestion was to build a drain field and use sand to absorb the juices seeping out of the landfill. Another was to drain the leachate into containers and then treat it. Neither was considered feasible.

An impounding dam was built in 1972 to collect the leachate, according to the Lebanon Daily News. No information on how the leachate was treated was included.

The state Department of Environmental Resouces (DER), the precursor to today’s state Department of Environmental Protection, wanted GLRA to install an electric-operated aeration in the impounded water to deal with the leachate. But Franklin Meiser, GLRA executive director at the time, argued against that because of cost.

The disagreement escalated with the assistant attorney general writing GLRA that “the landfill was causing pollution of the waters of the Commonwealth in that there was inadequate treatment of the leachate generated by the landfill,” according to a June 7, 1974, news story.

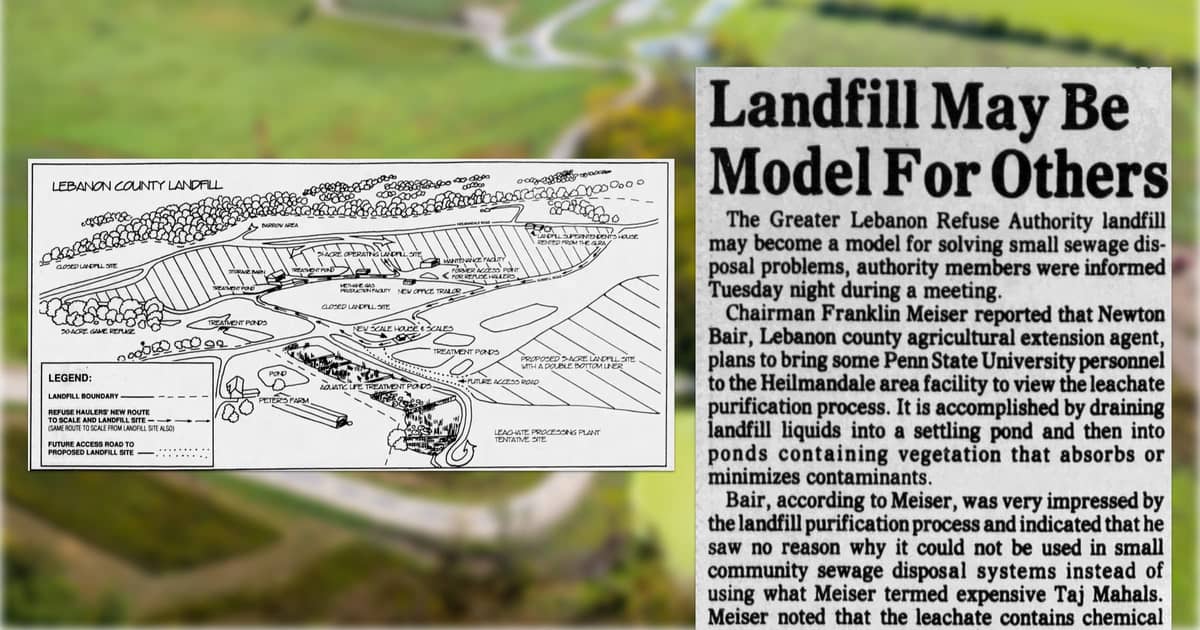

Meiser proposed constructing a series of lagoons or shallow ponds to collect the leachate, and in July 1974, GLRA began doing that. The hypothesis was the shallow ponds would contain the leachate and thereby eliminate potential contamination of any streams or drinking water wells in the area.

In March 1975, GLRA added another impounding dam, which created another shallow pond. Purifying vegetation such as cattails and bulrushes were planted to break down the leachate and other pollutants. DER eventually approved the lagoon-pond system, the first and only such system for municipal use in Lebanon County.

In February 1977, Meiser proposed six additional marshy ponds with wetland-loving plants. DER agreed to the pilot program, and the following spring, GLRA employees began constructing the expanded system.

Within a year, the pond system was purifying liquids draining from GLRA’s old landfills, and water quality exceeded allowable state standards, according to the Lebanon Daily News.

DER officials eventually conceded that what by then was called the Natural Aquatic Life Treatment System (NALTS) was a success.

Today GLRA’s pond system continues to treat leachate and runoff from several closed landfills. Routine testing of the water confirms the NALTS and wetland plants are doing the job of purifying the liquids.

Read More: Greater Lebanon Refuse Authority’s one-of-a-kind pond system goes with the flow

Questions about this story? Suggestions for a future LebTown article? Reach our newsroom using this contact form and we’ll do our best to get back to you.

Keep local news strong.

Cancel anytime.

Monthly Subscription

🌟 Annual Subscription

- Still no paywall!

- Fewer ads

- Exclusive events and emails

- All monthly benefits

- Most popular option

- Make a bigger impact

Already a member? Log in here to hide these messages

Free local news isn’t cheap. If you value the coverage LebTown provides, help us make it sustainable. You can unlock more reporting for the community by joining as a monthly or annual member, or supporting our work with a one-time contribution. Cancel anytime.