Earl Ziegler may not have been the first Lebanon County farmer to sell his agricultural conservation easement rights, but he was among those who first realized that preserving farmland is a worthwhile endeavor.

The Bethel Township farmer was such a big believer in the concept that he was one of the first to sell his development rights in perpetuity to become an early adopter of farmland preservation in Lebanon County. He began the process of placing 113 acres into the program the same year it was launched in the Lebanon Valley.

Thirty-three years later, over 190 agricultural easements totaling over 22,200 acres have been set aside in the county’s farmland preservation program, according to the Lebanon County Conservation District, the agency that administers the initiative here.

Now 96, Earl said he believes he preserved his farm shortly after the program was created by state law in 1988. The first farms were preserved in Lebanon County in 1992.

“I think it was ’92. I don’t remember the year,” Ziegler said. “But we were one of the first.”

Forever and a day

Craig Zemitis, agricultural land preservation specialist with the conservation district, said Ziegler is listed in their records as the 10th preserved farm in Lebanon County, officially being recognized on Aug. 18, 1994. “It is possible he filed his paperwork in 1992 and was recognized in 1994 because the process does take time to complete,” noted Zemitis.

Earl’s wife, Pat Ziegler, said he had discussed entering their farm into the program but wasn’t sure if it would be selected if they did apply.

A reason for that belief is that soil quality is a major factor in which farms get selected, and those above U.S. Route 422 are generally considered less desirable than farms south of that line. The Ziegler farm is a few miles north of Fredericksburg in Bethel Township and sits at the base of Little Mountain on Wildflower Lane.

“He thought about having it preserved and he thought, ‘Well, he doesn’t have a chance.’ And somebody told him he should, you know, put your name in for it because others weren’t doing it. And so we got picked then,” Pat said.

Before that could happen, however, an agricultural security area, consisting of a minimum of 250 acres, had to be created. Established by law in 1981, ASAs are zones that, in part, help prevent nuisance ordinances from being written so that farmers can conduct sound agricultural practices on their land.

“We signed some other people up for an agricultural security area,” said Earl. “And actually it was a banker from another bank that talked me into signing up. He was encouraging me to go in.”

While the banker was a backer of farmland preservation in those early years, many farmers were skeptical of not only a new and untested program but particularly one that was government-driven.

“I know there were people that said to him, ‘Why did you do that? You shouldn’t do that,’” Pat said. “They were really against it. … Good friends of ours … couldn’t see it.”

A home that sons Randy and Richard built for their dad sits high on a hill at the base of Little Mountain on the upper portion of the farm. The sweeping view for miles from the home’s front yard is magnificent, with Fredericksburg and other landmarks far beyond visible in the valley below. Today, Randy, 69, rents the land from his dad to grow corn, soybeans and rye as a crop farmer.

“At night you’d think there’s a city down through here with all the lights from the warehouses and all that,” Randy said. When asked if his land will ever be developed no matter how close development encroaches on his property, Earl gave a firm “nope” as his response.

It’s evident that the Ziegler family strongly supports the program, with Randy saying that a common belief at one time – which has since been proven to be wrong – is that preserved farms do not hold their value compared to non-participating farms where farming is intended.

“It’s far been disproven with what farms that are preserved are believed to be worth,” said Randy. “In fact, preserved farms are almost more desirable (than non-preserved) and they definitely hold their value.”

100 and counting

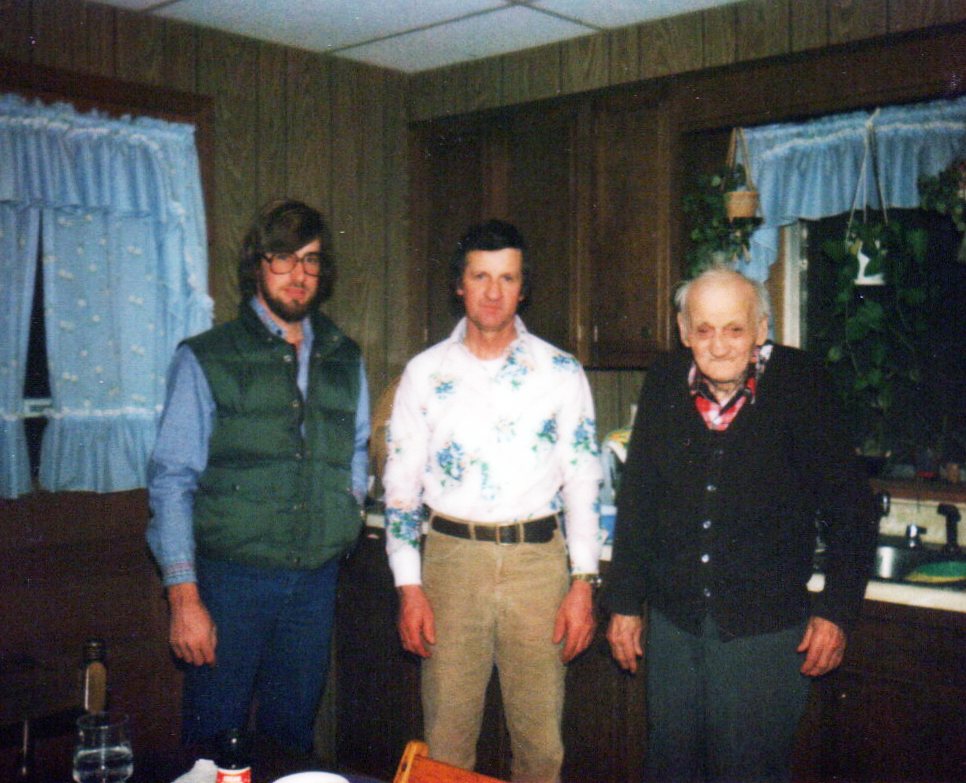

Both Earl and Randy have lived their entire lives on the farm, now in the family for 107 years.

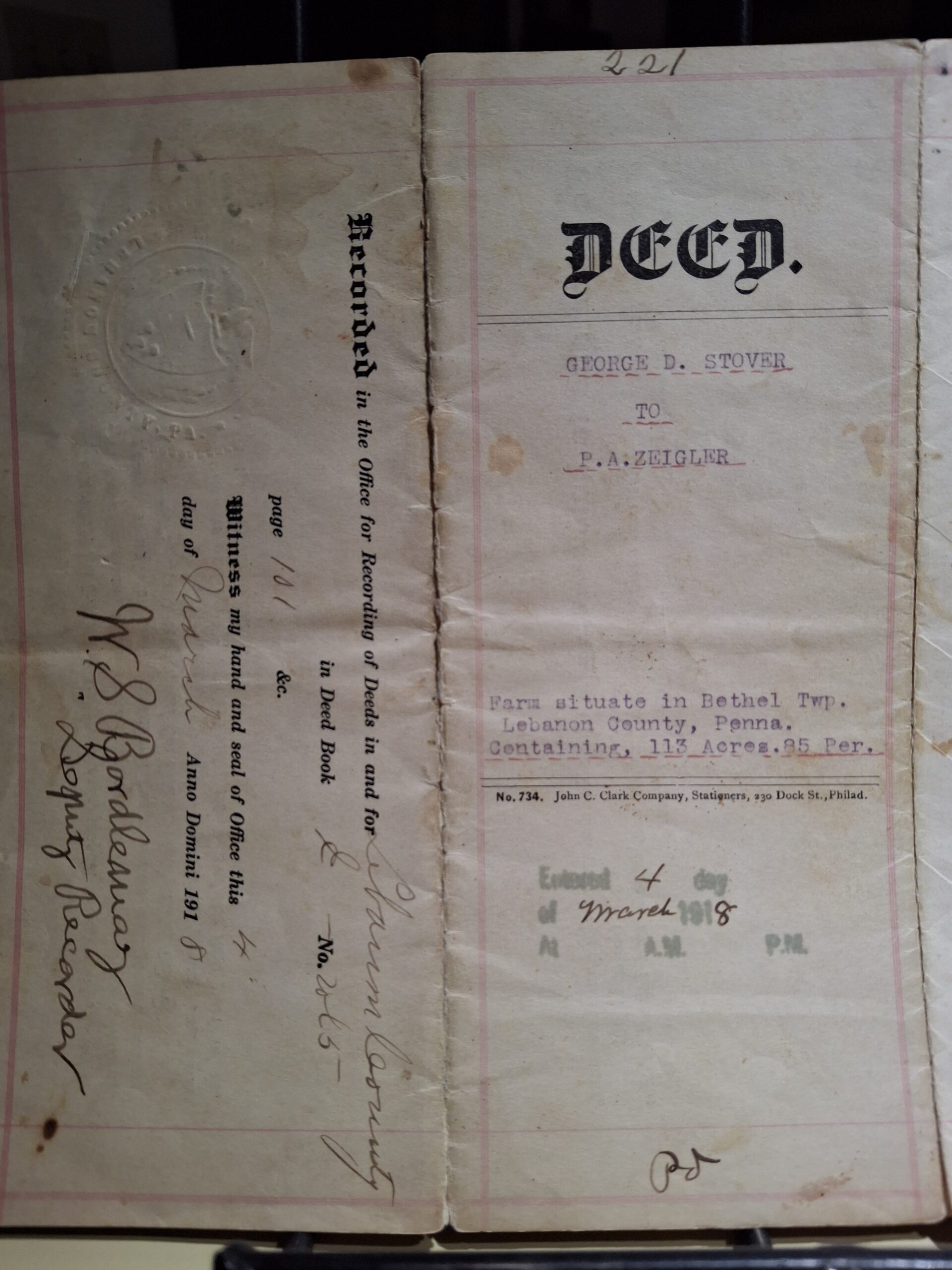

Earl’s father, Philip Ziegler, bought 113 of the current 171 acres in 1918 – a few years before Earl was born in 1929 – for $2,600, according to the 1918 deed from George D. Stover. (Earl would later add 58 adjoining acres when he purchased the Oscar Wolfe farm in 1962 to grow his operation.)

Randy jokes that he’s never ventured too far from the farmstead during his lifetime. Earl, in fact, was born in the white farmhouse that is now rented to tenants while Randy has his home on their land. Randy also lived for a time in the former Wolfe homestead.

“I would have lived in the (white) farmhouse and then in the apartment,” Randy said, adding that he then built his house on the farm, jokingly adding he hasn’t “got too far in life” by living so close to home.

Philip was a man of many talents. He was a harness maker by trade in addition to being a farmer – although Earl said his father’s ability to do physical labor on the farm was hampered by arthritic hands.

At one point, Philip placed an ad in a register owned by the Fredericksburg Eagle Hotel to advertise his business. That register, used to list the names of hotel guests and other pertinent facts during their stay, is now in the family’s possession. Dated entries for guests are noted as early as 1916, a few years before Philip purchased the farm, now in its third generation of ownership by the Ziegler family.

Unlike Philip, farming was Earl’s life-long profession. Philip, who lived from 1886 through 1981, owned his harness business from 1909 to 1918 at 118 N. Mechanic St., Fredericksburg, according to local historian Kathy Bicksler Stouffer.

“Well, I guess I was just a little bit more into it,” Earl says when asked why he grew his operation over the years by buying additional land and sole profession.

Earl said a reason to grow was to feed the cows, with Randy noting especially in dry years when harvests aren’t as hearty due to a lack of rainfall. Earl averaged 60 milking cows, 25 heifers, hogs and around 2,000 chickens that were egg layers when he was farming full-time.

Earl said he never encountered avian influenza while he had chickens on the farm. Unlike broilers that are raised quickly and shipped to market, the flu is more likely to be in layer populations since those birds have longer lifespans.

“It wasn’t a modern (chicken) house,” Randy said about theirs when it still existed. “Well, what dad had always told me was – or what he was always told was – ‘If you could see a chicken house from your farm, you shouldn’t have one.’”

Asked why, Randy said because of the potential for the spread of disease. “Now you can look and throw a stone and hit about 10 of them in any direction,” he added.

Changes down on the farm

That’s one change both have witnessed in the industry over the years. LebTown asked both for their opinion on the biggest changes in the agricultural industry that they’ve witnessed in their lifetimes since Earl farmed for about 80 years and Randy around 65.

“The change from horses to tractors,” Earl said. “I’m not milking by hand. This was a big help, too.” (He said he milked cows manually until 1950.)

Saying that his father always stayed with animal-driven power over engine-fueled power, Earl did operate tractors when he was young even though his father refused to drive one. Earl said his father also used horses to clear the land when a gas pipeline was installed through the land in the early 1920s.

“This pipeline that was put in in 1921, my dad dropped the (steel) pipes,” Earl said. “He also got a job in the township as a laborer. (Back) then they were different. They finally formed a crew where they had a roadmaster and two workers. He got into that and that’s when I became more heavily involved (in the farm).”

Randy said he had two answers to the changes he’s witnessed through the years.

“A cab on the tractor,” Randy said about the first modernization. “And then dad was the one that kind of was interested and I actually wasn’t quite as much because my main job was always plowing and working the ground. And he used to seed. But he was kind of looking into no-till and then once I got interested in it, that was the biggest change for me, going to no-till (planting).”

Like father, like son

In many ways, Randy’s life has been a mirror image of his father’s.

In addition to both living on the farm their entire lives, both started working on it at a young age. Randy also purchased another nearby farm containing about another 60 acres. That farm was owned by the daughter of World War II hero Richard “Dick” Winters, whose story of bravery is told in the HBO miniseries “Band of Brothers.”

An enduring legacy

No matter what has been thrown at them and despite farming being one of the hardest and deadliest professions, the farm and the Ziegler family have outlasted hardships. A tornado destroyed the original barn in May 1929 – just months before Philip was born in July.

“Dad got the lumber from a place in Lickdale,” Earl said about the rebuild for the red-painted barn that still stands nearly 100 years later.

Then there were heavy winter snowstorms during the dairy years when Earl had to get his milk to the dairy to be processed before it spoiled. Randy remembers riding along as a young boy to help get milk to Fredericksburg during inclement weather.

“Ziegler Lane used to get drifted in, drifted shut when we used to have the hard winters,” Randy said. “It used to be closed and the milk truck couldn’t get in. They used to use the manure spreader. I was pretty young then, but we had milk cans, and the milk cans would get put on the manure spreader and hauled into Fredericksburg to meet the milk truck. The tractor had a snow plow on it so that you could plow your way into town.”

Drought and rainless periods when the crops need moisture the most to finish growing into maturity also take their toll.

For example, much-needed rain now that typically helps nourish soybeans to fill out their pods has been sorely missing this year over the past few weeks. That will impact production and cost the farm money when the beans are harvested.

“It’s going to be bad for the late (planted) soybeans,” Randy said. “The only thing they will do is put nitrogen in the soil for the next crop.”

Despite the hardships caused by weather that can’t be controlled, one enduring legacy the elements can’t touch is the love that is felt down on the farm.

Randy jokingly said that stepmom Pat is still a farm “newbie” despite her living there since 1981 when she married Earl.

Pat said she learned early on during her time on the farm not to volunteer for a job because once you do, it becomes assigned to you – for life.

And in yet another humorous tale of life on the farm, Randy noted that while other children his age received toys as Christmas gifts, he was given a much more practical if not farm-ready gift: A wheelbarrow. When he was 5.

“I think he was a pretty smart man, and he thought that’s one less shovel full of crap that he has to shovel,” Randy said, followed by a chuckle from the family patriarch.

“I was pretty smart, right?” Earl replied with a knowing smile, without missing a beat.

Questions about this story? Suggestions for a future LebTown article? Reach our newsroom using this contact form and we’ll do our best to get back to you.

Keep local news strong.

Cancel anytime.

Monthly Subscription

🌟 Annual Subscription

- Still no paywall!

- Fewer ads

- Exclusive events and emails

- All monthly benefits

- Most popular option

- Make a bigger impact

Already a member? Log in here to hide these messages

While other local news outlets are shrinking, LebTown is growing. Help us continue expanding our coverage of Lebanon County with a monthly or annual membership, or support our work with a one-time contribution. Every dollar goes directly toward local reporting. Cancel anytime.