We’re celebrating Lebanon County’s role in American history. Read more here.

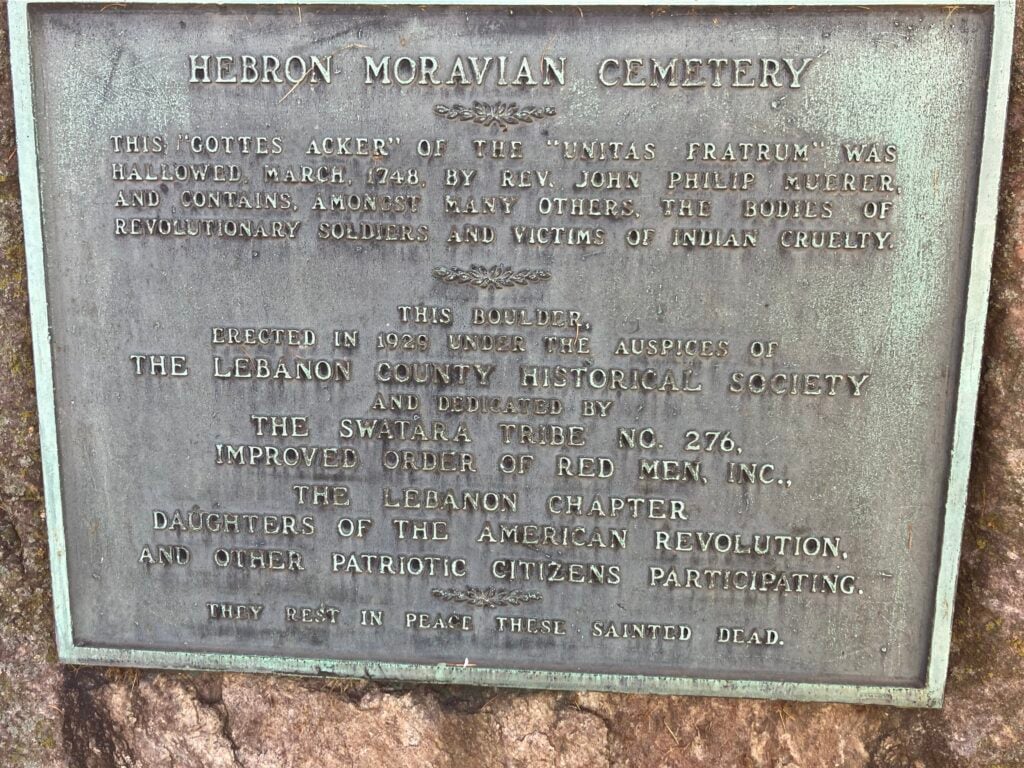

Founded in 1748, Hebron Moravian Cemetery in Lebanon was recently designated as a state historical site by the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania.

There are several reasons for this designation, according to cemetery board members John Klahr and Susan Dieffanbach.

The Pennsylvania Historical Museum Commission announced the decision to make it a historic site on Oct. 14.

“I can show you a recent internment that we had there are families, there are people buried there that have no marker but they will,” Klahr said, noting that everyone receives a grave marker. “If the family requests it, when there’s the service of internment the trombone choir comes and plays. We have been doing that since the 1740s too.”

Then there’s the way the deceased are interred, which is a hallmark of the Moravian faith.

The “choir system” for burial is a Moravian church practice where the deceased are buried according to their “choir,” or group, based on age, gender, and marital status, according to the two board members.

This system divides the graveyard into sections for men, women, and children to reflect how the congregation sat and socialized in life, symbolizing a continuation of the community in death.

“The plots, if you look at them, there’s that section over there, and there’s this section over here. So that’s the women’s side, and this is the men’s side,” Klahr stated, pointing out the delineation. “And they’re buried in choirs, married. The male (side) has strangers. So those were people that were not in the congregation that needed a place to be buried. Infants, single and married. And then the women had married, single, and infants. And there are a lot of infants in here. Because there were (many) at the time.”

The question of whether non-church members were permitted to be buried in the cemetery, which is located off of Cloister Street between Cumberland and Walnut streets in South Lebanon Township, was answered before it could be asked of the two cemetery historians.

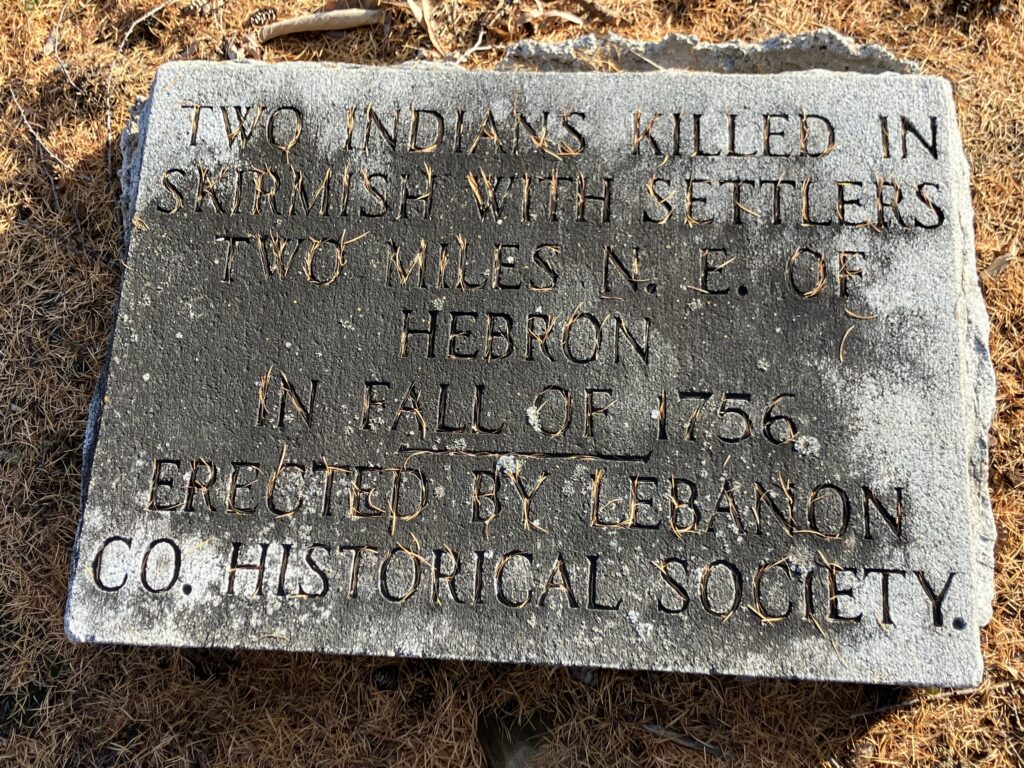

“They would get a (stranger) marker, and they were not, for example, the Indians that are buried here. No one would have them. You can’t put Indians in our cemetery. At the time, the cemetery was this acre, and they put them in the corner by themselves. But now the cemetery has expanded, and they’re in the middle of it,” said Klahr, who added that the strangers didn’t necessarily have to have any connection with the church. People were buried there regardless of their faith.

“They could be somebody that died that had no connection and no affiliation with anybody, and they just, they put them there,” said Klahr. “The Moravians opened up their hearts and put them in their cemetery.”

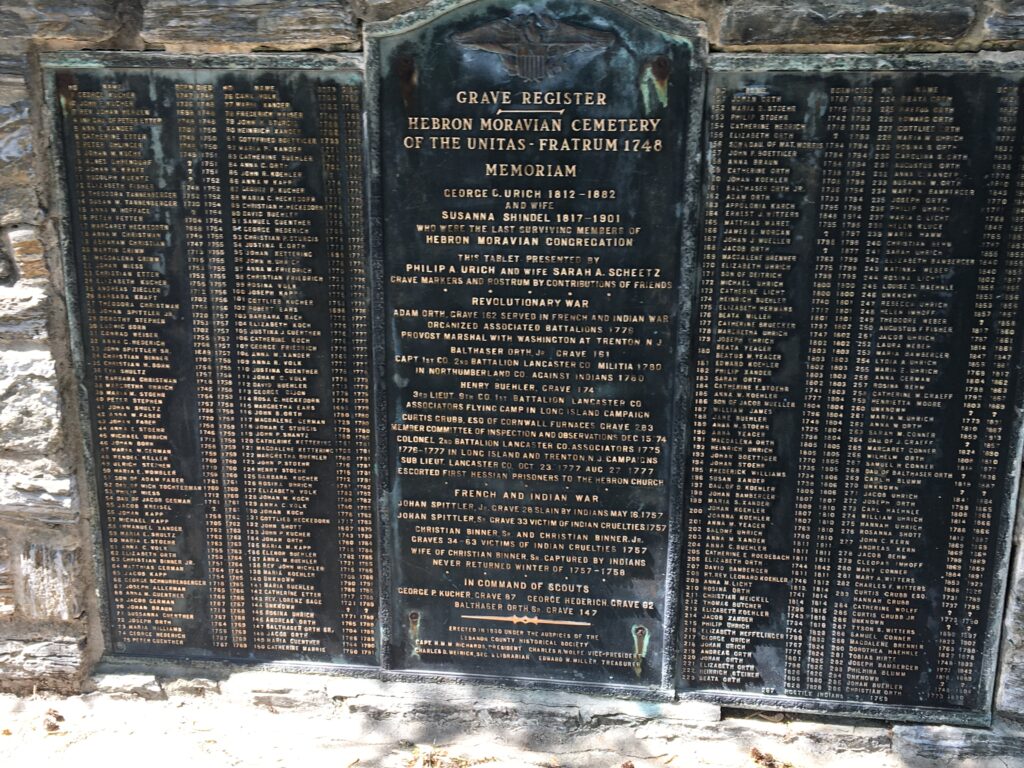

A cement rostrum in the cemetery bears the title “Grave Register Hebron Moravian Cemetery of the Unitas Fratrum (Moravian Church) 1748.”

It also pays tribute to several individuals and specifically the names and grave markers for those who served in the Revolutionary War, French and Indian War and those who were “In Command of Scouts.”

“The veterans are listed here for the American Revolution, of which we have some. And the French and Indian War. Civil War, Korea, War of 1812. And World War II all the way up to Korea,” said Klahr, although there is one there from Vietnam. “Well, he was in the service at the time of Vietnam. I don’t know if he served in Vietnam or not, but that would be the only one. And the reason we don’t have Vietnam veterans is Ford Indiantown Gap opened, and they go to the National Cemetery for free.”

The historians said there are 217 people buried in the cemetery’s “new” section and 223 in the old. All of those individuals in the old section – minus the two Native Americans – are listed on the cemetery’s grave register.

One notable change over the years is who can and cannot be buried there.

“They have to be a Moravian to buy the plot,” Diefenbach said. So that’s the restriction on the cemetery. And you go through the church.”

Tracing the cemetery’s early history is somewhat difficult, according to Klahr, because it was created 65 years before Lebanon County was founded. The cemetery was not next to the original church, which is a common practice today, but was located in the community of Hebron on the eastern edge of what was Steitztown, which was founded in 1740, before it became Lebanon City in 1885.

“This land was not owned by the church until some time later. The deeds are very, very hard to trace, because at the time when the internment started, this was part of Lancaster County,” Klahr said. “So the deeds for the very, very early years are in Lancaster County, and usually they’re in German.”

The settlers who came to America were from the nation of Moravia in Czechoslovakia. Moravia is a historical region in the east of the Czech Republic and one of three historical Czech lands. The church was founded on the teachings of Jan Hus, whose beliefs are believed to be the forerunner to the Moravian faith.

“The people came onto the estate of Ludwig, Count Ludwig von Zinzendorf, seeking refuge as they were kicked out of Moravia,” Dieffenbach said. “So they were known as Moravians. And they established a community there called Hebron, which is still a thriving community today.”

Another hallmark of the church was flat grave stones, which are evident in the cemetery’s old section.

“The Moravian belief was that we are all equal in death. So nobody’s going to put up big money in the dead,” said Klahr.

There are a few prominent Lebanon Countians buried in this cemetery, according to Dieffenbach.

“Peter and Curtis Grubb formed the Peter Grubb furnaces… The Felty family is here. They were prominent in Lebanon County,” Dieffenbach said “I mean, Dr. Felty was a dentist. His father is a veteran of World War I.”

Both agree when LebTown notes that cemeteries are a treasure trove of stories because everyone who’s buried there has one. Another well-known individual is David Tannenberg, a famous pipe organ builder.

David Tannenberg was a Moravian organ builder who emigrated to Pennsylvania. He is cited as the most important American organ-builder of his time. He constructed a number of organs during his lifetime, as well as other keyboard instruments. Many of the organs that he built are still in use.

“Well, that’s why we wanted to have it preserved and it’s historic, so it can’t be — it can’t be destroyed. And we have a program in place, we’ve done it a couple of times, ‘If These ‘Graves Could Talk,’” Klahr said. “It brings up the guys who were — did you say about the ones that were massacred? And the men who came, the families — so the French and Indian guys and all of them. Those people’s stories. And Hebron became a refuge for people, and actually Hessian prisoners were housed in the Hebron Church, which was used to house prisoners.”

Read More: The Paxton Boys, an early case of viral fake news witnessed from Lebanon’s Hebron Moravian Church

Dieffenbach said the cemetery does have what she called “legends.”

“We just wanted to keep it alive,” Dieffenbach said, adding that a bus tour may be organized for the America250 next year. “We do come every Easter. We have our Easter Sunrise service here. And we have our holiday service here.”

A special service will be held on Dec. 13 at 9 a.m. as part of the Wreaths Across America program, which honors those who served. The public is invited to attend this event.

Beyond the upcoming ceremony, Dieffenbach will work on getting national historic designation for the cemetery.

“So to get national designation, you must first be accepted by your state board and they won’t accept you if you don’t have a chance to go forward with the national. I got bogged down with some… issues, and I never have proceeded on the national (designation). I have the application started,” Dieffenbach said.

Both Klahr, who is involved with Cedar Hill Cemetery in Fredericksburg, and Dieffenbach will be buried one day here since both are members of the Moravian faith. For Dieffenbach, a number of her family members have Hebron Moravian Cemetery as their final resting place.

“So my great-grandfather is here. My great-great and my great-great and my grandfather, my mother and father, my husband and I will be buried, and I have plots for our kids and our grandchildren,” says Dieffenbach.

Questions about this story? Suggestions for a future LebTown article? Reach our newsroom using this contact form and we’ll do our best to get back to you.

Keep local news strong.

Cancel anytime.

Monthly Subscription

🌟 Annual Subscription

- Still no paywall!

- Fewer ads

- Exclusive events and emails

- All monthly benefits

- Most popular option

- Make a bigger impact

Already a member? Log in here to hide these messages

Local news is a public good—like roads, parks, or schools, it benefits everyone. LebTown keeps Lebanon County informed, connected, and ready to participate. Support this community resource with a monthly or annual membership, or make a one-time contribution. Cancel anytime.