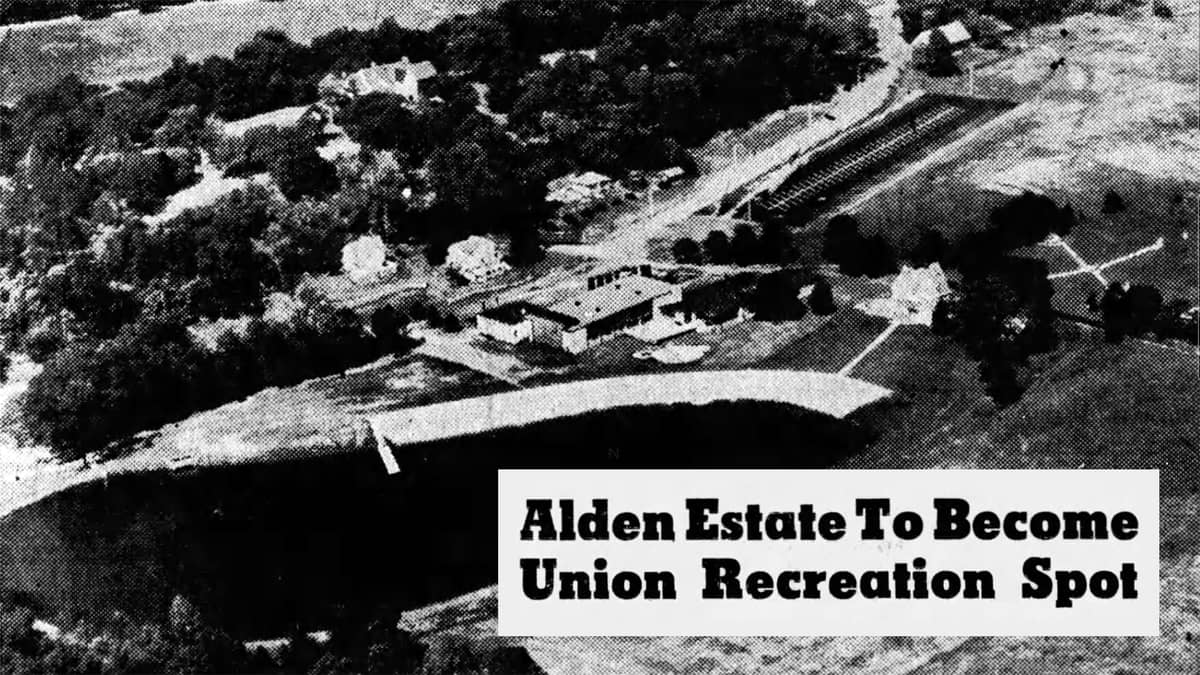

A huge tract of land west of Cornwall proper, once the lavish Gilded Age estate of a Coleman family heir, was transformed in the 1950s into a holiday complex for some 20,000 members of the Amalgamated Clothing Workers Union of America.

From one family’s concentration of wealth and local power to a shared home-away-from-home of thousands, the story of Union Center is among the most striking property transformations in the history of the Lebanon Valley.

It begins in the last decades of the 19th century with the Alden branch of the Coleman family, one of the state’s wealthiest industrial dynasties. Founding patriarch Robert Coleman’s expert dealings in the local iron mines and furnaces at Cornwall and elsewhere in the late 18th century and 19th century had founded a family empire worth many millions of dollars.

In the 1880s, Robert Coleman’s granddaughter Ann Coleman Caroline Alden (who acquired the Alden name from husband Captain Bradford Ripley Alden) decided to give her son, Robert Percy Coleman Alden, a particularly grand wedding present: a new mansion perched on top of a Coleman-owned hillside in west Cornwall. According to a Lancaster Online article about the mansion, the tract of land on which the mansion was built was just a fraction of the 5,000 acres owned by Ann across Cornwall.

The mansion, known then as Millwood but perhaps better known today as Alden Villa, was one of many Coleman mansions in Lebanon and beyond. Even by the standards of the Colemans, Millwood is special: it was designed by Stanford White of the architectural firm McKim, Mead & White. White, along with his partners, are considered giants of American architecture, designing for some of the richest families of the Gilded Age in the late 1800s — and the extended Coleman family at the time certainly fell into that milieu. The Colemans were among the firm’s earliest clients; Ann had first hired them several years earlier for a mansion all her own: Fort Hill, located on Long Island’s “Gold Coast.”

The mansion is still standing though it is closed to the public; a video tour of it was created in 2016 by Savi You.

Construction on the mansion began in 1881, the same year that John Percy Coleman Alden was born in New York. He was the son of Robert Percy and his wife Mary Ida Warren, making him the great-great-grandson of Robert Coleman. Though no expense had been spared on Millwood, it found itself little used as a long-term residence by the Alden family, who tended to keep to New York.

After the death of his mother, father, and brother, John Percy was left with the Millwood estate and the property, over 520 acres in all, surrounding it. Never married, he was reported in 1949 to have lived in the mansion in his last years with his lawyer, doctor, and chauffeur. On Christmas Eve, 1948, the 66-year-old John Percy died in New York.

The Alden estate went up for sale during a four-day auction held in the mansion’s “ballroom” in September of 1949, receiving a lot of attention from parties in the area and beyond for its assortment of antiques and assets. The massive plot of land in Cornwall, which included the mansion, was sold on September 16 to Jule Monas, a representative of the union and wife of PA Joint Board manager David J. Monas, on a bid of $88,000.

A change of owners

The Amalgamated Clothing Workers Union of America (ACWA) was a national labor organization formed in 1914 representing garment workers in the US. It was one of the founding unions of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) in 1935, initially a rival federation of unions to the American Federation of Labor (AFL); both of these merged together in 1955 to form the AFL-CIO, still the largest and most influential union organization in the country.

The AWCA had in fact pounced on the property during one of the strongest decades of union power in US history. Over a third of American workers were members of a union during the mid-1950s, and the Alden purchase was a signal of confidence from the union and for the labor movement in general.

The newly refurbished property, now dubbed Union Center, was dedicated at a ceremony on August 27, 1955 with thousands of Lebanon union members in attendance. Among the officials involved were PA Attorney General Herbert Cohen and ACWA vice president Hyman Blumberg, as well as local and regional union officials. ACWA members within 100 miles of Union Center, some 20,000 in total, were invited to spend their holidays at the property as a perk of union membership.

“Today in Pennsylvania we are just beginning to contemplate overall statewide recreational facilities. Here today we find the Amalgamated has beaten us to it,” said Cohen, who had aided the Pennsylvania branch of union organizers as a lawyer in the 1930s.

Union Center had much to recommend it. The ACWA had spent several years adding to its features and amenities, and hosted educational seminars, film screenings, sports games, recreational activities, picnics, and other events. They had funded the renovation process by earmarking 25 cents of each member’s weekly dues for the endeavor, in time accumulating over a million dollars, according to a contemporary article in the Pottsville Republican. Yearly taxes on the property were then reported to be $1,600.

Among the buildings constructed by the union was Hillman Hall, a recreation hall capable of seating 700 named for late ACWA president Sidney Hillman. Also new to the property were several outdoor cooking areas, a swimming pool, basketball courts, an open pavilion, six cottages, and a children’s playground. 260 acres of the property was set aside for farming, which had also been used as such under Alden ownership.

One major change to the landscape was the addition of an artificial lake (described at various times as 5 acres and 2.5 acres in surface area) and a sand beach. This lake was fed by a private reservoir that the Alden mansion had also utilized. Also under construction nearby was a “complete bathing facility,” including bath houses and a diving pier, and the lake itself was in a prime position to be viewed from a sundeck attached to Hillman Hall.

Millwood, a truly giant residence of 11,223 square feet, was still a focal point on the property. At the time of its sale, it included a dining room, library, living room, drawing room, kitchen, pantry, a great hall with a musicians’ gallery, and maid’s kitchen on the first floor (a full two stories tall); five master bedrooms and three bathrooms on the second floor; and five more bedrooms and a bathroom, in addition to storage space, on the third.

Aside from some kitchen updates and the installation of new bathrooms, the union is reported to have “completely preserved” the mansion, while still using it as a residential space for at least some of its members. Through the use of Millwood and its cottages, Union Center could host around 40 people overnight at the time of its dedication. The nearby White-designed carriage house was also under union ownership (since its construction in 1881, it has been moved from its original location).

For decades, Union Center was truly a center for union activities and garnered a reputation as a special place that labor organization had made possible. The Hazleton Standard-Speaker, in anticipation of the 30th anniversary celebration of the PA Joint Board of the ACWA, described it in 1963 as “one of the most famous union recreation and education centers in the country.” Numerous events and ceremonies, as well as leadership meetings, took place at the center over the years.

The end of an era

By the 1980s, however, unions were feeling the effects of a decline in union power across the country. This process began in the late 1960s, continued during the high inflation and economic instability of the 1970s, and accelerated with the election of President Ronald Reagan in 1980 and the breakup of a strike in 1981 often regarded as a major defeat for union power in US labor movement history.

The ACWA had merged with the Textile Workers Union of America in 1976 to form the Amalgamated Clothing and Textile Workers Union (ACTWU) (ultimately, the current union UNITE HERE, representing some 300,000 workers, is in part descended from the ACWA). For the ACTWU, the general weakening of unions was compounded by a decline in the US garment manufacturing industry as production began to migrate overseas.

At the time it was put up for sale in 1983, John Swoboda, international vice president of the Pennsylvania Joint Board of Clothing Workers, explained that the union had enjoyed a heyday from the 1950s through the early 1970s, but had hemorrhaged half of its members in the subsequent decade. In fact, since 1980, a third of its plants had closed. The Union Center property had served its purpose well for nearly three decades, but after spending millions on it throughout that period, the ACTWU decided to put it up for sale.

Rumors began swirling about the sale of the property to one of two church organizations. The first was the Faith Evangelical Mission of Pennsylvania, headed by Rev. Robert Fyffe. In an attempt to expand outward from the four churches he headed in Illinois, Fyffe and his organization purchased the property in November of 1983, mansions and valuable belongings included.

Fyffe wanted to develop a Bible college, accommodations for 500 people, and housing for the elderly on the property, while retaining the charm of the “little ol’ church down the lane,” as described by LDN reporter Hugh Lessig. Now a 296-acre parcel put up at a price of over $2.5 million, the property was then the object of the largest non-commercial real estate deal in the history of Lebanon County.

Until it fell through. Fyffe’s mission had collapsed before even beginning to raise the $250,000 needed for a demand note due to the union by early February. With the deal dissolved, Fyffe tipped off the second church organization to the purchase of the property — one much bigger than his own.

This time, the property was being eyed by Rev. Robert Schuller (NY Times obituary), televangelist and founder of the megachurch Crystal Cathedral in California. According to a local realtor in 1984, Harry Fisher, Schuller was interested in the property as possible grounds for a “renewal center” and spiritual center to expand his reach to the eastern side of the country.

In the end, though, neither of the two Revs. Robert got their hands on the property. Schuller was prevented from acting thanks to an agreement the union had made with Missouri-based Lee F. Sutliffe Associates, Inc., which planned to build a nursing home on the property. Even that deal did not proceed. By 1988, the property found itself in a state of limbo, though it was no longer owned by the union. It remained unused until the early 2000s, when Louis Hurst and his development group unveiled plans for the construction of its current development, Alden Place, which opened in 2005.

Since then, befitting a retirement community, the Alden plot has been fairly quiet. Alden Villa was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2011. Alden Place has retained some of the Union Center features, most obviously the lake, but there is little left today that hearkens back to its days as union property.

Recently, there’s been two major pieces of news for the property — Hurst purchased the nearby defunct Quentin Riding Club for $2.1 million in 2019, and two parcels of Alden Place land were sold for $18 million in 2020. What exactly these changes will bring to the area is yet to be seen.

The remarkable history of the property as it unfolded over the course of 140 or so years is perhaps not well-known today. In its time as Alden land, it reflected the great wealth and wane of Lebanon County industrial royalty, and in its time as Union Center, it became a similarly extravagant perk of union membership, until the union faced a decline of its own. It’s a piece of property that has changed with the times, and it may well be worth keeping an eye on to see what the next decades will bring.

Questions about this story? Suggestions for a future LebTown article? Reach our newsroom using this contact form and we’ll do our best to get back to you.

Support Lebanon County journalism.

Cancel anytime.

Monthly Subscription

🌟 Annual Subscription

- Still no paywall!

- Fewer ads

- Exclusive events and emails

- All monthly benefits

- Most popular option

- Make a bigger impact

Already a member? Log in here to hide these messages

An informed community is a stronger community. LebTown covers the local government meetings, breaking news, and community stories that shape Lebanon County’s future. Help us expand our coverage by becoming a monthly or annual member, or support our work with a one-time contribution. Cancel anytime.

This article was corrected to remove a description of Louis Hurst as “late.” In fact the developer remains quite alive and continues to make news in Lebanon County. Watch for more on LebTown about his plans for the Quentin Riding Club property in the coming weeks.