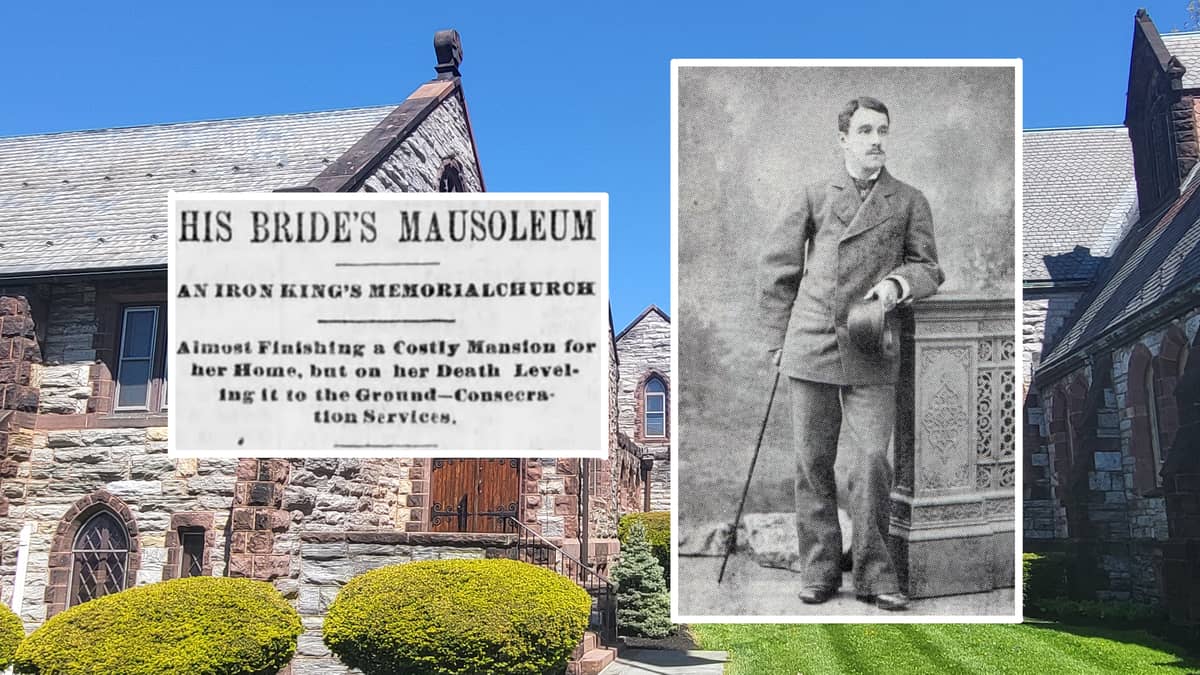

It’s one of those tidbits of local history that gets pass around as accepted fact: after the sudden death of his wife Lillie, young industrialist Robert H. Coleman demolished a mansion under construction in Cornwall and sent the stones to be used in the construction of St. Luke’s Episcopal Church.

While the story offers a poetic origin for one of Lebanon’s most beautiful stone churches, several historians have pointed out discrepancies in the timeline of events. As Robert H. Coleman is one of LebTown’s most-covered historical figures, it seemed only natural to try to get to the bottom of the history.

The timeline

Robert Habersham Coleman was born March 27, 1856, the great-grandson of ironmaster Robert Coleman. A year later, on Nov. 8, 1857, the first service among what was to become the congregation of St. Luke’s was held at a private Lebanon residence, according to a history supplied by St. Luke’s.

William Coleman, father of Robert Habersham, was among the vestry when the congregation officially organized in 1858 as Christ Church of Lebanon. (The name would change to St. Luke’s in 1865.)

In 1861, William died, leaving behind funds dedicated to the church for use in purchasing property. A first church was built in 1863 at the corner of Sixth and Chestnut streets. William’s widow Ellen continued to support the parish for decades, including through the funding of parochial schools, several “Public Reading and Recreation Rooms,” and a children’s home that came to be known as Talbot Hall.

A second church at the same location (where it towers today) was built beginning in 1879; the cornerstone was laid on Oct. 18, the feast day of St. Luke, and the consecration followed exactly one year later in 1880.

Meanwhile, Robert Coleman had grown into a young man with the resources of a vast inheritance at his fingertips. During his education at Trinity College in Hartford, Connecticut, he met Lillie Clarke, eventually marrying her in January 1879.

Lillie fell ill shortly after marriage, resulting in the couple taking a restorative tour of the southern United States. Before leaving for the South, Robert proposed the idea of a new mansion for Lillie and their future family to Artemus Wilhelm. Wilhelm was Robert’s business and financial manager and had been put in control of the Coleman iron operations before Robert was old enough to take control of his entire estate. Wilhelm was on board with the idea.

The plans for the new mansion progressed as the year continued and Lillie’s health was seemingly restored. Construction began in October 1879, and the young couple left for Europe with the intent to purchase furnishings and artwork. Robert continued to correspond with Wilhelm about the mansion’s progress from across the Atlantic.

But disaster struck. Lillie, whose health had always been delicate, fell deeply ill with “Roman Fever,” a name for malaria, and the trip was lengthened to focus on restoring Lillie’s health. The couple traveled to Paris, where Lillie died on May 10, 1880.

A grief-stricken Robert returned to Cornwall with the body of his wife. Though work on the new church of St. Luke’s was underway, he halted construction and interred Lillie’s remains within the church crypt. A May 27, 1880, column in the Lebanon Daily News recounts the burial services that took place on May 26, describing in detail the homecoming of the widower via boat and then train.

Lillie’s remains were interred that day “in a new vault just finished under the chancel of the new St. Luke’s,” and the private family funeral was concluded with the hymn “Nearer my God to Thee.”

Lillie’s remains were subsequently reinterred at the Laurel Hill Cemetery in Philadelphia following Robert’s second marriage to Edith Johnstone in 1884. All three are buried alongside other Coleman family at the Laurel Hill plot; Edith having died in 1903 and Robert in 1930.

What about the mansion?

The greatest misconception about the story is the identity of the incomplete mansion in Cornwall. Richard E. Noble’s 1983 graduate thesis “The Touch of Time” is a well-known biography of Robert H. Coleman, which is still available as a booklet from the Lebanon County Historical Society.

Although Noble’s research is extensive, he made a mistake in identifying a photograph of a building named Cornwall Hall as the unfinished mansion stopped in 1880.

Cornwall Hall was in fact an entirely different unfinished mansion erected by Robert H. Coleman, and its construction did not begin until 1886. Designed by the renowned architects and brothers George Watson and William Dempster Hewitt, the Victorian three-story mansion was an “addition” to the residence of Robert’s mother Ellen. Her home, referred to as “the Cottage,” was designed by John McArthur Jr. and finished in 1878.

Located in the field opposite Toytown across Cornwall Road, Cornwall Hall was a massive expenditure for Robert (over $130,000) and construction on it was halted in 1891 for unknown reasons – some researchers, such as the late John and Margery Feitig, have speculated that Robert’s funds were getting tight. During the Panic of 1893, the failure of Robert’s investments in Florida’s railroad industry caused him to lose much of his fortune, and he departed the Lebanon area for good, having never lived inside Cornwall Hall.

The uninhabited building was guarded until it was dismantled beginning in 1914; it may have taken several years to raze the entire building. Several LDN notices from 1914 report the theft of brass and copper, which was stolen while the mansion was being taken apart in February and March of that year.

Many historians have pointed out the obvious discrepancy in the timeline between the deconstruction of Cornwall Hall and the construction of St. Luke’s. It is less known, however, that there was an earlier mansion that was also located in Cornwall, constructed for Robert H. Coleman, and left unfinished.

The first mansion

In the late 1870s, Robert began planning a mansion that would serve as a home for Lillie and their eventual family. An architect employed by the Colemans, Washington Bleddyn Powell, was tasked with the design of the new mansion; Powell sent initial drawings to Robert in early 1879 and construction began by October.

Powell had in fact been previously employed under John McArthur Jr. when the latter was the Philadelphia City architect; Powell later assumed the title himself.

The correspondences between Powell and Robert are kept in the Pennsylvania State Archives. A large body of research material compiled by the aforementioned Feitigs includes copies of the letters; the material is now in the possession of the Cornwall Iron Furnace.

One such letter written by Powell on June 9, 1880, details the aftermath of the halted mansion construction. This 17-page letter provides insight into the expenses and materials of the mansion in the state it was in at the time of demolition, with the total cost between October and May summing up at over $48,000.

Unlike Cornwall Hall, no photographs of the Powell mansion are readily available, if they exist at all. The architectural drawings were kept by Robert H. Coleman and are believed to be lost. A Lancaster Intelligencer report from the time of Lillie’s death reported that, before being destroyed, the back walls of the Powell mansion had reached a second floor though the front lacked any brickwork.

Jim Polczynski, president of the Friends of the Cornwall Iron Furnace, published an article for the Lebanon County Historical Society in 2019 explaining the differences between Robert’s two unfinished Cornwall mansions, titled “Clarifying the Colemans.” LebTown spoke to Polczynski about the earlier mansion and the research that has been conducted over the years.

According to Polczynski, the most likely location of the first mansion was just west of the still-standing gatehouse or stable building north of Cornwall Methodist Church (another Coleman project designed by McArthur). The dilapidated building was designed by Powell.

The entire property, including the gatehouse and the former sites of both the Powell mansion and Cornwall Hall, is still in private hands after a different branch of the Coleman family, the Freemans, purchased the plot in 1903.

So was the mansion stone ever used for St. Luke’s?

At the time of this writing, LebTown was unable to locate any record of the leftover mansion stones being sold to St. Luke’s. In an exchange with LebTown, church historian and archivist Terry Heisey stated that no church records show such a transaction occurring, though he added that both the church and mansion utilized some of the same quarries for supplies.

This is referenced in Powell’s letter of June 9, in which he noted that “the Church was supplied for a part of the time from the same locality from which we derived our supplies and afterwards from a greater distance during most of the winter months.” Powell also described the state of the leftover material at Cornwall, but makes no reference to St. Luke’s, instead proposing that they go towards other unrelated projects:

“In consequence of the subversion of the New House a very large amount of building material will be accumulated on the site. To the end that the dressed stone shall not receive injury from breakage or the absorption of earthy substances, I have caused the same to be carefully placed under cover in the stone-shed. These may be utilized in the New Office or the proposed School Building spoken of.”

In conversations with LebTown, Polczynski recalled viewing a two-page itemized list of building materials that noted that stones leftover from the Powell mansion were sold at a minimum cost to St. Luke’s, but this document has not been found. If the stones were indeed sold, the church does not have the record and reports on construction in the following years (such as the adjacent choir room) do not mention of any connection.

It is a confusing coincidence – and a testament to the wealth of Robert H. Coleman – that two mansions were partially constructed in the same vicinity and eventually abandoned.

Special thanks to Jim Polczynski, Terry Heisey, Mike Emery, Bruce Chadbourne, and Bruce Bomberger in the researching of this article.

Questions about this story? Suggestions for a future LebTown article? Reach our newsroom using this contact form and we’ll do our best to get back to you.

Keep local news strong.

Cancel anytime.

Monthly Subscription

🌟 Annual Subscription

- Still no paywall!

- Fewer ads

- Exclusive events and emails

- All monthly benefits

- Most popular option

- Make a bigger impact

Already a member? Log in here to hide these messages

Our community deserves strong local news. LebTown delivers in-depth coverage that helps you navigate daily life—from school board decisions to public safety to local business openings. Join our supporters with a monthly or annual membership, or make a one-time contribution. Cancel anytime.