Nearly nine months after the death of Andrew “Andy” Dzwonchyk, an investigation by Lebanon County District Attorney Pier Hess Graf into possible criminal charges for the Pennsylvania state trooper who fatally shot him appears to be stalled.

Apparent slow play of Dzwonchyk investigation by DA leaves case in legal limbo

“The investigation is still ongoing,” said DA Hess Graf in an email to LebTown. “For obvious reasons, we do not publicly release details in any case of any investigative measures or steps done by law enforcement.

“We are still actively working on it; as such, we are unable to render a final determination.”

LebTown has been unable to confirm that any investigators have been back to the scene or interviewed eyewitnesses since the days immediately following the shooting, and it’s not clear whether neighbors or eyewitnesses had been interviewed at any point following the shooting.

The autopsy and coroner’s report of Dzwonchyk, obtained by LebTown through an open records request, show that the initial death investigation was completed last December.

LebTown asked Hess Graf to elaborate on the “obvious reasons” for withholding details of the investigation; however, the DA did not respond to further followup emails. With Dzwonchyk dead, it’s not clear what public safety concern could lay behind the refusal to share any updates or potential timeline for the investigation to conclude.

Hess Graf also did not respond when asked if the delay of the investigation was based on legal strategy.

Paul Messing, a partner in a civil rights firm in Philadelphia County, has been retained by the Dzwonchyk family. It is LebTown’s understanding that they are closely monitoring the situation.

As the New York Times reported in January, Dzwonchyk was the fourth Pennsylvanian to be fatally shot by Trooper Jay Splain. The first fatal shooting occurred in Lehigh County in 2007; the second in Northampton County in 2017.

The third occurred in Lebanon County in March 2020, when Splain shot Charity Thome in Jackson Township following a car chase through the county. Hess Graf closed an investigation into the Thome shooting five weeks after the incident took place, and has said she has no plans to reopen it, despite growing scrutiny around the findings.

DA’s husband was Splain’s supervisor at time of Thome shooting

In June, the New York Times reported that Hess Graf’s husband, Pennsylvania State Police Cpl. Christopher Graf, was Splain’s supervisor at the time Splain fatally shot Thome. The Times reported that Cpl. Graf moved to a training position in June 2021 and was not supervising Splain at the time he fatally shot Dzwonchyk.

Prior to the Times reporting, Hess Graf had said to LebTown that her husband had “nothing to do with this incident or investigation.”

Splain is currently on “administrative duty,” which a Pennsylvania State Police spokesperson told LebTown is standard policy for a trooper who is involved in an officer-involved shooting that remains under investigation. Splain has not faced criminal charges for any of the previous three shootings, and PSP would not say whether Splain has ever faced internal disciplinary action, citing confidentiality policies.

The apparent conflict of interest for Hess Graf regarding her husband’s involvement in the shootings lies at the center of an outstanding ethics complaint filed by the Lebanon County branch of the NAACP against the DA.

All Pennsylvania attorneys, including prosecutors, are required to follow the Pennsylvania Rules of Professional Conduct, which include specific provisions for prosecutors, including that “a prosecutor has the responsibility of a minister of justice and not simply that of an advocate.” The state Supreme Court has held that a prosecutor must exercise independent judgment in prosecuting a case, be “disinterested and impartial,” and that “even in the absence of an actual conflict [of interest]” … the DA’s continued participation can create “the appearance of unfairness and undermines confidence in the proceedings.”

Additionally, Pennsylvania law makes district attorneys subject to the same ethical rules as county judges in regard to conflicts of interest. Those rules require prosecutors to avoid the appearance of impropriety in performing their duties, even if an actual conflict may not exist.

Hess Graf previously said that the NAACP’s complaint was “meritless” but otherwise did not substantively address whether at minimum she may have the appearance of impropriety with respect to her impartiality on the case.

“He had no factual information as to the shooting, the circumstances which led to the shooting, or the investigation which immediately started thereafter,” said Hess Graf, referring to her husband, in a June press release responding to the NYT’s reporting. “As such, per the policy, no conflict existed and my Office investigated the incident.”

Complaints against attorneys submitted to the Disciplinary Board of the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania are initially private, and in most cases only become public if the board, based on its investigation, recommends that the Pennsylvania Supreme Court punish the attorney for an ethical violation. The party filing a complaint is however informed of the outcome of complaints, such as whether it was dismissed as unfounded or referred to the Supreme Court for disciplinary action. An NAACP spokesperson said that the organization has not heard any updates on the complaint since it was filed.

Read More: NAACP files complaint against DA over investigation of fatal PSP shootings

County judge, AG say they did not review conflict of interest policy despite DA’s claims

Hess Graf told the Times that she had consulted with the president judge of the Lebanon County Court of Common Pleas before establishing the referenced conflict of interest policy (PDF). A LebTown interview with Lebanon County President Judge John C. Tylwalk in June put that claim into question.

“We did have a meeting to discuss whether or not there should be some policy and my recollection, I guess my notes of that conversation indicate that I told her that I believe that if there was a use-of-force situation or if her husband was involved, even tangentially, the better move would be to bring in the attorney general’s office,” said Tylwalk. “And then the next thing I heard, I received a copy of the memorandum where they had consulted with the attorney general’s office and developed the policy that was developed. I wasn’t involved in actually developing the specifics of it or anything.”

The policy itself also states that the DA “consulted with the Pennsylvania Office of Attorney General.” Molly Stieber, press secretary for the Pennsylvania Office of Attorney General, previously told LebTown in a statement that their office did not assist Hess Graf in creating a conflict of interest policy for Lebanon County’s district attorney’s office.

“Generally speaking, District Attorney’s offices regularly contact the Office of Attorney General’s criminal division to discuss potential conflicts or seek advice since our office serves as the agency to which cases involving conflicts or resource needs are referred,” Stieber wrote. “While we can provide advice on potential conflicts or the appearance of one, District Attorneys are under no obligation to follow that advice and we do not review any internal policies for counties as to what constitutes a conflict. We did not review the language in Lebanon County’s policy.”

In addition to concerns around Hess Graf’s conflict of interest with the investigations, questions remain about what specifically happened on the nights in question, and the extent to which official police narratives are representative of those facts.

Use of deadly force in both incidents may have gone against state law, PSP policy

According to Pennsylvania law, deadly force is justified only when such force is necessary to prevent an arrest from being defeated by resistance or escape and the person to be arrested has committed or attempted a “forcible felony” (such as murder, rape, arson, or aggravated assault) or is attempting to escape and posses a deadly weapon, or otherwise indicates that they will endanger human life or inflict serious bodily injury unless arrested without delay.

In the cases of both Thome and Dzwonchyk, police have said or implied that a moving vehicle presented imminent risk of serious physical harm to a state trooper, which necessitated use of deadly force. The Pennsylvania State Police policy for shooting at a moving motor vehicle requires that either the vehicle is being operated in a manner that poses an imminent threat of death or serious bodily injury to another individual, or that by some other means the vehicle operator or passenger poses an imminent threat of death or serious bodily injury to another individual.

NLPD officer says he wasn’t in fear of his life when Thome’s vehicle struck cruiser; dash cam footage shows 5 mph impact

In August 2021, Philadelphia law firm Kline and Specter filed a federal civil rights lawsuit (PDF) on behalf of the Thome estate against Splain and Pennsylvania State Trooper Matthew Haber. The lawsuit claims that “this was not a justified shooting and … constituted excessive, unnecessary force, in violation of Ms. Thome’s constitutional rights” and alleges that the the account of the events as described by Splain and Haber is not corroborated by video of the shooting the firm obtained via a subpoena.

Read More: Civil lawsuit filed against troopers in 2020 Jackson Township fatal shooting

LebTown is sharing clips from that video for the first time today.

The video comes from the dashboard-mounted camera of a North Cornwall Township Police Department (NCTPD) vehicle. Kline and Specter attorneys allege that the video contradicts certain aspects of the police narrative regarding Thome’s shooting. Furthermore, an initial legal response by the Office of Attorney General Josh Shapiro (PDF) to the lawsuit seemingly upholds key discrepancies between the initial police narrative and what the Thome estate contends occurred in its suit.

The chase, which began when police obtained an arrest warrant for Thome in the early hours of March 16, 2020, after she allegedly tried to break into a former North Lebanon Township residence twice in a 24-hour period, lasted about 15 minutes and spanned approximately 15 miles, according to LebTown estimates based on the video. County dispatch records show that the first call for a disturbance at Thome’s previous residence on the 1700 block of Heilmandale Road was made at 2:02 a.m. In a half hour’s time, Thome would be dead.

About three miles from Thome’s former residence at the intersection of Route 72 and Tunnel Hill Road/22nd Street, an NCTPD officer joined North Lebanon Township Police Department officer Ryan Haase in the pursuit. Video of the pursuit comes from the dashboard camera on that NCTPD cruiser.

In Hess Graf’s press conference declaring the Thome shooting as justified, the DA stated that Thome was throwing “auto parts” out of the vehicle at pursuing vehicles. A LebTown analysis of the video has not yet identified any such moments or debris lying on the roadway, but according to the state, Haase said that Thome was throwing objects from the driver’s side window attempting to strike his vehicle and that he believed she was trying to disable the vehicle.

Approximately 14 minutes into the chase, Haase can be heard telling dispatch that he was going to terminate the pursuit, just as PSP troopers joined the chase.

“I don’t know who all’s behind me right now but I’m about to terminate,” said Haase in a radio call audible in the NCTPD video.

Thome estate attorneys quote Haase in the suit as saying that he did not feel the public was in danger because the time of the incident was early in the morning. In a response to the suit, attorneys for the state denied that claim as stated, but offered no further characterization of the extent to which Haase felt Thome presented a risk to the public if the chase was terminated.

Immediately after Haase tells dispatch that he was going to terminate the pursuit, someone – presumably the NCTPD officer – can be heard saying, “You’ve got PSP between us here.”

In the video, PSP can then be heard requesting permission to perform a Precision Immobilization Maneuver (P.I.T.), a pursuit tactic by which a pursuing car can force a fleeing car to turn sideways abruptly, causing the driver to lose control and stop.

The PSP troopers then apparently perform the PIT on Thome’s vehicle, although the maneuver itself isn’t visible in the video. Thome’s vehicle can be seen leaving the road, spinning 270º into a field, and knocking into a street sign in the process. The vehicle can then be seen stationary for a few seconds before it begins to lurch from the field, onto the shoulder, and into the NLTPD vehicle in front of it.

In the civil suit, lawyers for the Thome estate said that the vehicle was moving at 5 miles per hour when it struck Haase’s parked North Lebanon Township Police Department vehicle. The state confirmed that estimation in its response to the suit, saying that Haase believed Thome’s vehicle was moving at 5 miles per hour when it struck his vehicle.

According to the state, Haase said that the impact did not jolt his cruiser and that he did not feel in fear for his life when Thome struck his vehicle. The state confirmed that at the time he saw Thome driving towards his vehicle, Haase said that all he could think was “do not hit my car, bitch do not hit my car.”

No airbags were deployed in either vehicle as a result of the impact.

The state said in its filing that Thome ignored verbal commands from Splain and Haber after her car was spun off the road. Splain can be seen in the video exiting the vehicle first, followed by Haber a second later. No verbal commands issued to Thome can be heard in the dash-cam recording.

Thome estate attorneys said that in his deposition Splain estimated thirty seconds elapsed between when he got out of his vehicle to when he and Haber began shooting, and that the trooper said he was giving Thome commands the entire time. Far fewer seconds appear to have actually elapsed between when the vehicle was forced off the road and shots were first fired. The video shows that the car had ceased moving by the time Splain reached it, standing directly in front of the NLTPD cruiser.

Attorneys for the Thome estate said that Haber and Splain were supposed to have a lapel microphone on their person at all times, including at the time of the incident, but that they claim to have lost their microphone earlier in the evening in question when they were, as they were quoted as saying, tending to an injured deer. The state contested this claim generally in its response to the suit without elaborating in further detail, but did admit that the troopers thought the microphone fell off during a prior call on their shift.

At one point in its response, the state says that Splain yelled “Stop” one last time and that Thome then reached down towards the passenger compartment as if she was grabbing something. However, the state offers a slightly different order of events elsewhere in the same document, saying that Splain estimated he shot four or five shots in quick succession, after which Thome continued moving and appeared to be reaching for something, so Splain then proceeded to fire one or two more shots.

The state said that Haber also fired two shots at Thome. In the lawsuit, Thome estate attorneys said that Haber was on his first day as a Trooper following a coaching period. The state generally denied this claim, although it did not refute it in specific detail. The Times had also previously described Haber as a “rookie” cop in its reporting.

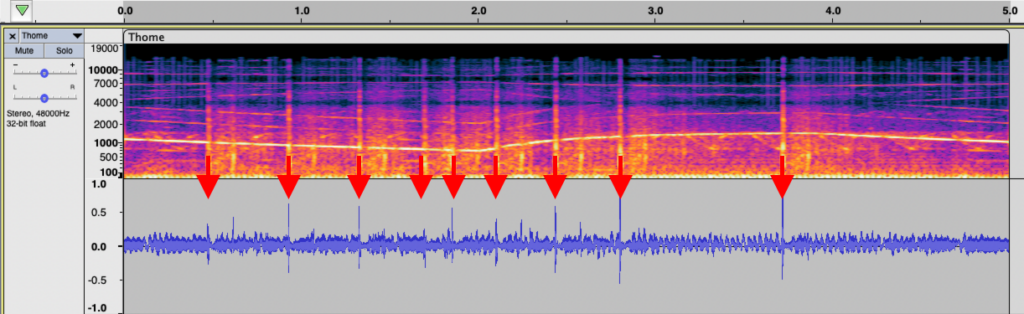

A LebTown analysis of the video audio suggested that closer to nine shots were fired in total.

Other than the contradictory statements about Thome reaching for something in her vehicle, the state did not elaborate in its response to the lawsuit about why Splain or Haber felt the use of deadly force was necessary.

When Hess Graf declared the use of deadly force as justified in a press conference some five weeks after it took place, she said that the troopers were unsure if the North Lebanon officer had gotten out of the cruiser and feared that Thome might be able to strike that officer or another with her vehicle. In her press conference, Hess Graf also said that a large metal railroad spike was found in Thome’s car, although this object is not mentioned in the state’s filing or any other source.

Read More: DA discusses details, process that led to justified shooting finding in Thome death

Autopsy records show that Thome was shot seven times, including five shots that entered in her back. The autopsy report states explicitly that shots are not identified in the chronological order in which gun wounds may have been incurred and it’s not otherwise known in what order the shots were fired.

According to coroner records, a trooper from the PSP Forensic Services Unit – Michael Stramara – was also present for the autopsies of both Thome and Dzwonchyk. Three total troopers attended the autopsy of Dzwonchyk, including one corporal, Christopher Zukowsky. Although it’s unclear what, if any, influence PSP may have had over autopsy results by having troopers in the room with medical examiners, it’s an example of the close relationship that coroners have with law enforcement – one that raises questions of conflict of interest and independent judgement.

Trooper not injured in car scuffle that led to Dzwonchyk being shot twice in the head

The shooting of Dzwonchyk occurred Sunday, Nov. 7, 2021, in Union Township, after troopers were dispatched over a Protection From Abuse violation by Dzwonchyk for visiting the home of ex-girlfriend Amy Hastings, whom he had dated for 20 years and with whom he had two children. Hastings told the Times that she had left the relationship because she was weary of Dzwonchyk’s drug use.

According to the Times, Hastings obtained the PFA after Dzwonchyk badgered her to reenter the relationship and talked of killing himself in front of their two sons if she did not come back.

“Andy never threatened me or the kids,” Hastings told the Times in an interview.

Hastings called 911 around 10:40 p.m. on Nov. 7 because Dzwonchyk kept texting her in violation of the PFA order, according to the Times report. Two troopers showed up – one of them Splain – in response to the call. Hastings was staying at a residence down the road from Dzwonchyk’s house, the Times reported, and at the time, Dzwonchyk was caring for their sons.

Hastings told the Times that while the troopers were on site, Dzwonchyk texted again and said he needed a thermometer for one boy who was sick. Hastings then went inside because it was cold, after which Dzwonchyk showed up.

Pennsylvania State Police said they attempted to arrest Dzwonchyk while he was in the car when a “scuffle occurred,” according to the autopsy report, and Dzwonchyk put the vehicle –a 1999 stick-shift Volkswagen Beetle according to the Times’ reporting – into reverse and forward while a trooper was partially in the vehicle, dragging but not hurting him, according to the police account.

“I don’t think (the vehicle) was very fast at all,” said Pennsylvania State Police spokesperson David Boehm at a press conference the next day.

Police said that the second officer on site that night – identified as Splain – initially deployed his Taser twice before discharging his firearm into Dzwonchyk. Boehm said that the Taser had no effect on Dzwonchyk.

According to the autopsy report, seven casings were found at the scene, with eight shots believed to have been fired by Splain.

The autopsy states that Dzwonchyk died due to multiple gunshot wounds, five in total, including two gunshot wounds on the head and face. The autopsy report also indicates that Dzwonchyk had been tased twice, with one of the probes embedded in the skin of his right chest and the other embedded in his jacket.

With police alleging that another trooper was partially in the vehicle at the time Dzwonchyk was shot, it’s unclear how Splain could have discharged his weapon or Taser without putting the other trooper at risk. Three of the shots went unaccounted for in the autopsy.

PSP said that first aid was given to Dzwonchyk by both troopers, and EMS also responded, but Dzwonchyk was pronounced deceased at the scene by the Lebanon County coroner’s office.

Families say that police responded to mental health crises with unnecessary deadly force

Representatives of both Dzwonchyk and Thome have presented the incidents as being first and foremost mental health crises, not as potential threats to public safety.

Both Dzwonchyk and Thome had high levels of methamphetamine in their systems at the time of the deaths, according to toxicology reports.

In the civil lawsuit, the Thome estate’s attorneys said that Thome’s history of mental illness and substance abuse was known to police prior to the incident, and that the officers could have used substantially lesser means than killing Thome to deescalate the situation. In its initial response to the suit, the state confirmed that Splain and Haber were aware that Thome was a known methamphetamine user.

“Their job was to talk her out of the vehicle and into safety,” said Thomas Kline in an interview with the Times. “And instead, they did just the opposite, which was to fire multiple rounds of bullets into her pinned-down vehicle, leaving her defenseless and tragically dead.”

Autumn Krouse, Dzwonchyk’s sister, had previously told LebTown that it’s a shame that a common denominator in all four shootings involving Splain were related to individuals who were suffering mental health issues.

“There is no place for someone to kind of have a nervous breakdown,” said Krouse. “The common thread is these people were all unraveling and it feels in our society there is not a time nor a place where that is a good idea. It seems like such a deeper problem.”

Krouse told LebTown that her impression was Splain didn’t have the capacity to deal with a mental health episode, or any level of patience or tolerance for one.

“Even the most mentally sound people have times when everything is falling apart,” said Krouse.

PSP policy calls for officers dealing with persons who may be suffering from mental illness or mental health emergencies to “take steps to calm/de-escalate the situation, when feasible,” “assume a quiet, non-threatening manner,” and “provide reassurances that you are there to help and that they will provided with the appropriate care.”

The federal lawsuit over Thome’s shooting is currently scheduled for trial on Nov. 21, 2022. There has been no docket activity in the case since December 2021.

In cases such as this, the state will often argue that its officers have “qualified immunity,” a controversial legal doctrine that shields public employees from liability they would otherwise face when accused of violating others’ constitutional rights. Exceptions to qualified immunity typically include conduct that knowingly violates clearly established statutory or constitutional rights of which a reasonable person would have known.

Attorneys for the Pennsylvania State Police are currently attempting to use this doctrine to get a civil lawsuit against Splain and another trooper over the 2017 Northampton County shooting of Anthony Ardo dismissed in a summary judgement, a preemptive ruling made by the court when it believes there are no significant disputed facts that need to be decided at a trial, and that one party is entitled to win some or all of its claims immediately. That motion remains pending and undecided.

In the Thome lawsuit, the deadline for either party to move for summary judgement is Aug. 12, 2022.

No civil lawsuit has been filed over the Dzwonchyk shooting at this time. The statute of limitations for federal civil rights lawsuits, such as the one filed by the Thome estate, is variable depending on the type of underlying violation. In most cases, the state’s statute of limitations applies. Pennsylvania has a two-year statute of limitations for death actions, so Dzwonchyk’s estate would have until Nov. 7, 2023, to file suit.

Chris Coyle and James Mentzer contributed reporting to this article.

Questions about this story? Suggestions for a future LebTown article? Reach our newsroom using this contact form and we’ll do our best to get back to you.

Support Lebanon County journalism.

Cancel anytime.

Monthly Subscription

🌟 Annual Subscription

- Still no paywall!

- Fewer ads

- Exclusive events and emails

- All monthly benefits

- Most popular option

- Make a bigger impact

Already a member? Log in here to hide these messages

Our community deserves strong local news. LebTown delivers in-depth coverage that helps you navigate daily life—from school board decisions to public safety to local business openings. Join our supporters with a monthly or annual membership, or make a one-time contribution. Cancel anytime.