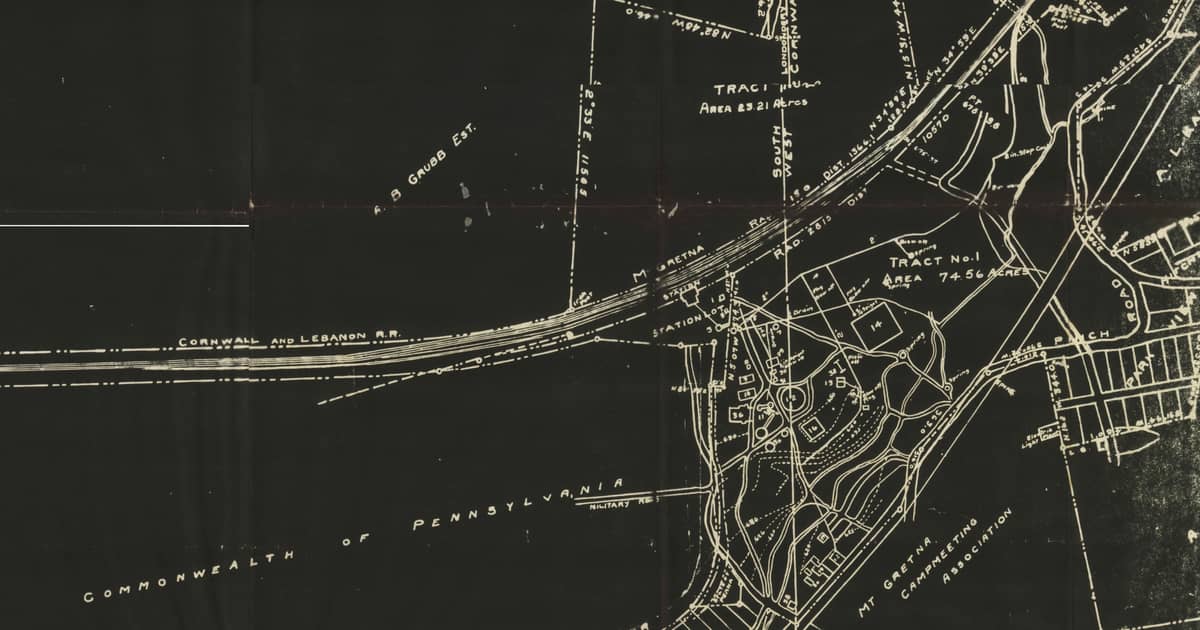

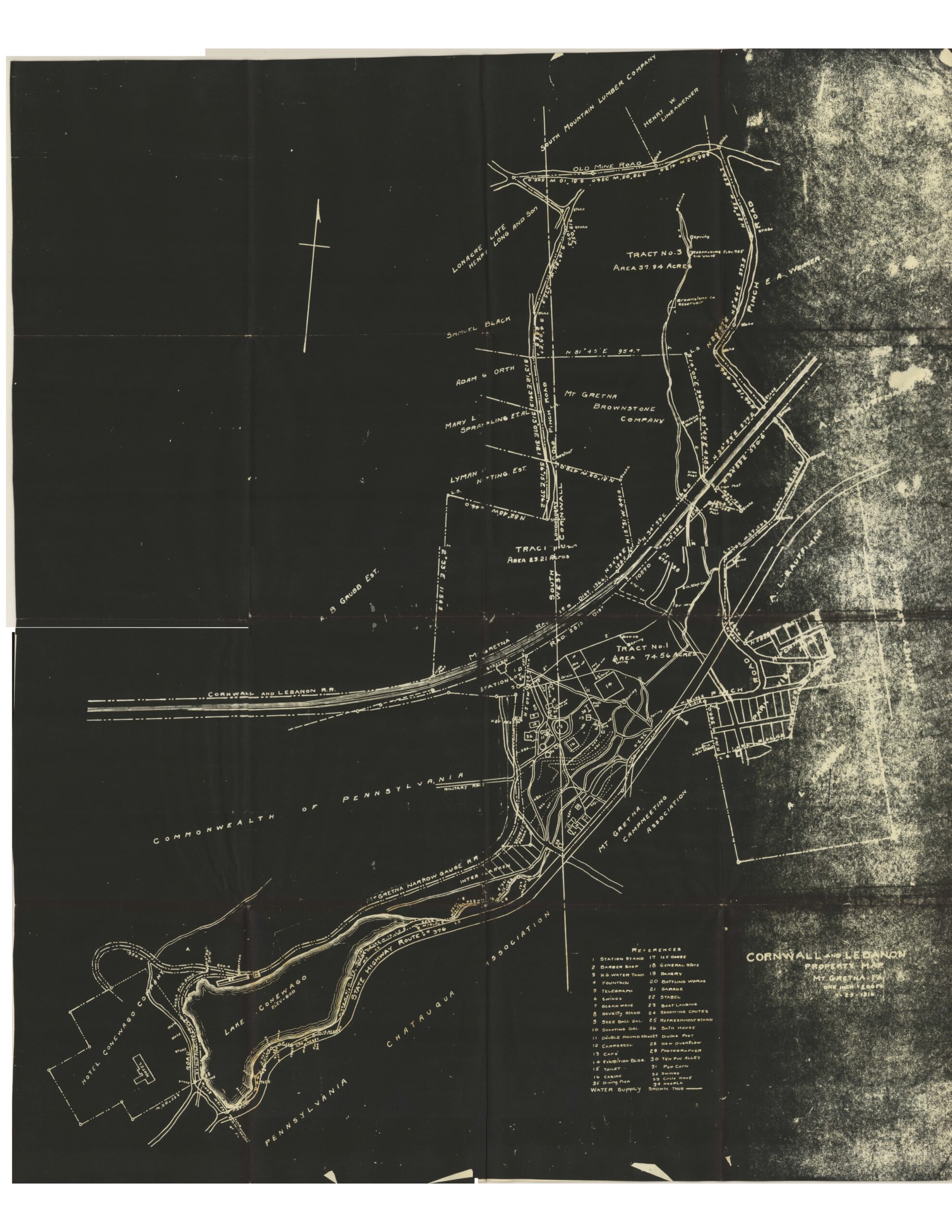

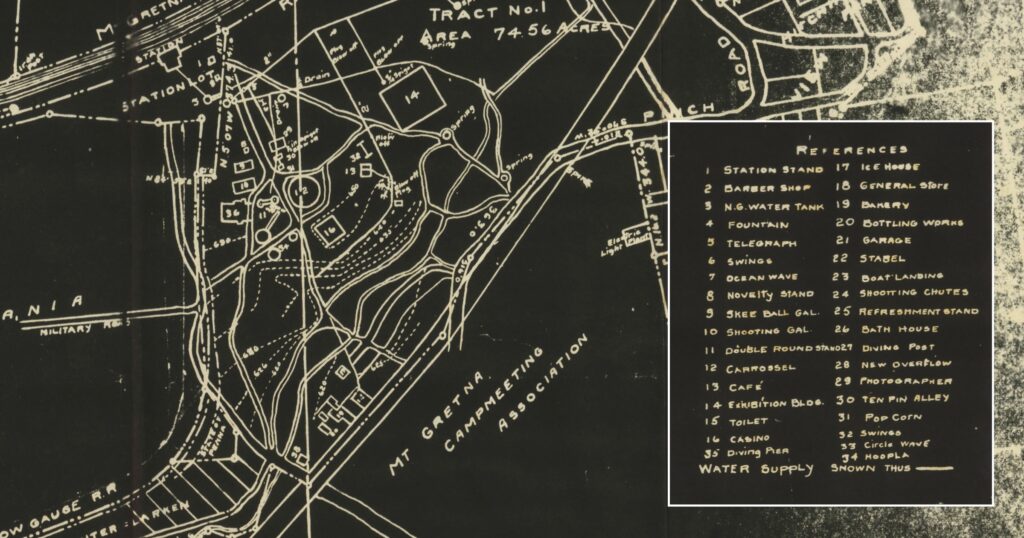

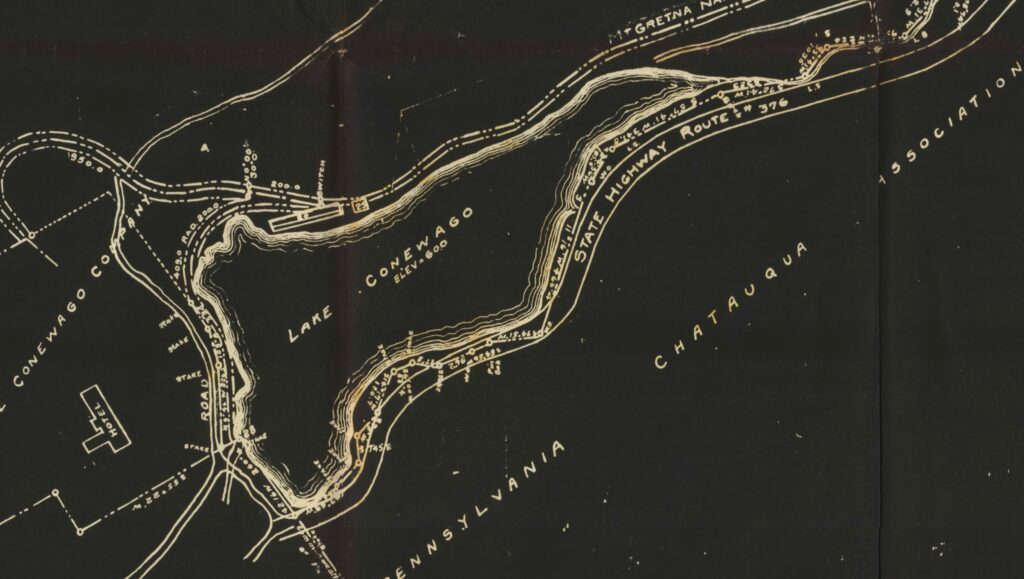

A maze of crisscrossing lines, a cluster of tiny hand-drawn shapes and a numbered list of “References” — these appear on a “1916 Cornwall and Lebanon Property Map, Mount Gretna, Pa.”

Nothing else on the map has the same detail as that which is found in Tract No. 1, a 74.56-acre parcel that once was Mt. Gretna Park.

Most of the numbered structures are long gone. The telegraph (#5) was replaced by the telephone, the icehouse (#17) by home ice boxes and later, refrigerators. The “stabel” (#22) disappeared as well — also made obsolete by new technologies. (See a version of the map overlaid on contemporary satellite images here.)

Read More: Lebanon’s ice industry turned winter temperatures into cold cash

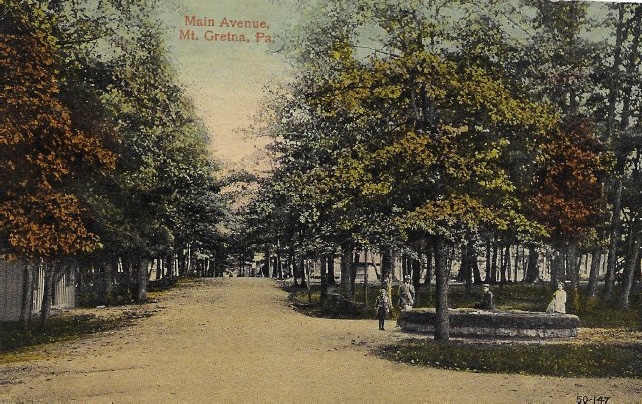

But a few vestiges remain. The sandstone fountain (#4), once a popular gathering place, still borders the path from the Lebanon Valley Rail Trail into Gretna, and a sign on a building erected on the footprint of the original general store (#18) even now announces “Mt. Gretna Park.”

A snapshot from another century, the map gives a glimpse into the amusements that once captured our ancestors’ attention and imaginations. But it also tells us something about how we lived in the late 1890s and early 1900s, and what has changed or been lost over time.

Picnics, dancing, boating, and more

Developed in 1884 as a station stop on the Cornwall & Lebanon (C&L) Railroad, the park initially was a picnic grove with rustic tables and benches, swings for children and woodland walking paths. Even in its first summer, those simple attractions drew more than 50,000 visitors, according to news reports of the day.

Recognizing the park’s potential as a go-to destination, railroad magnate and park developer Robert H. Coleman added a pavilion for dancing, bowling alley, lawn tennis and shooting gallery for summer 1885 — and folks from Lebanon and neighboring counties flocked to Mount Gretna.

Next, he had Conewago Creek dammed, and Lake Conewago was opened for boating. A scenic narrow-gauge railway followed. Mount Gretna, declared the Lebanon Daily News in July 1889, “has become without question, the most attractive park in Pennsylvania.”

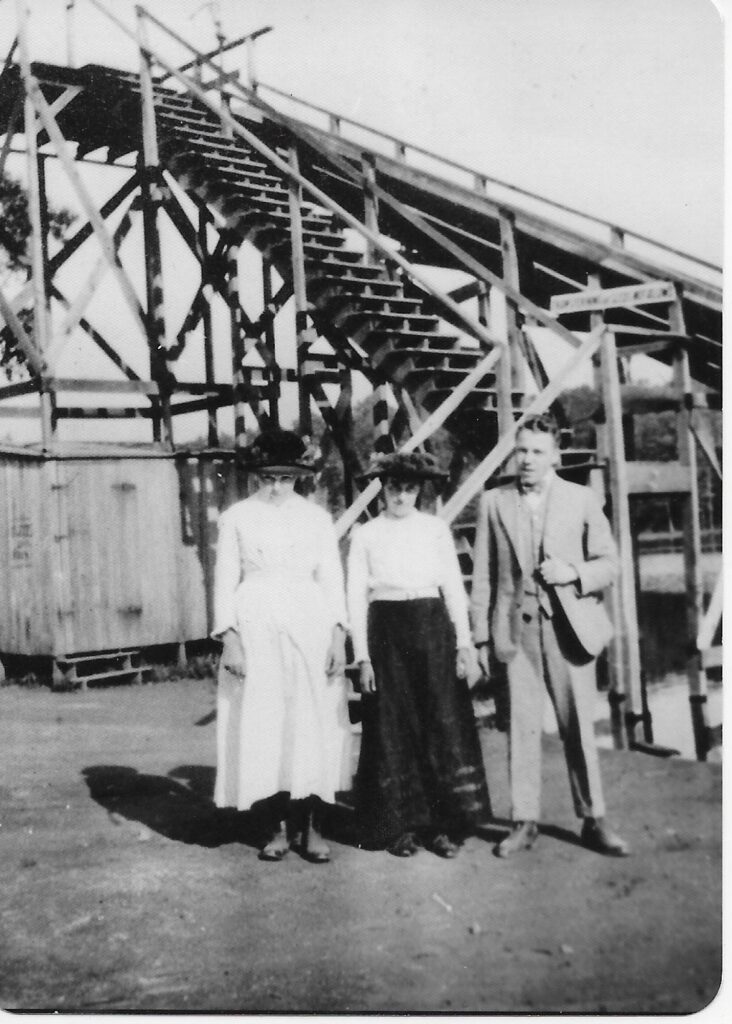

A decade after its start in 1884, Mount Gretna Park had a carousel “of the latest improved pattern,” an auditorium that could seat 3,500, and 16 large platforms for dinner parties and other activities, according to the C&L brochure, Mount Gretna Park: 1884-1891.

A casino, skee-ball gallery, and ten-pin bowling alley were among the amusements in place when the map was drawn in January 1916.

But the park also contained more practical structures including a bakery and café. Some of these may have been added by Frank Dissinger and John Lesher, two Campbelltown businessmen who, starting in 1897, were the “park caterers,” operating a dining hall that could seat 400.

By summer 1901, the two men had leased the “park privileges” which apparently meant they managed not only all of the park’s dining facilities but also all of the amusements including Lake Conewago. As lessees, they added “a very fine, artistic roof over their merry-go-round,” according to the Lebanon Daily News, as well as a number of bath houses at Lake Conewago.

They also opened several stores, one of which (#18) is pictured on the map. In what sounds like a reference to today’s mini-marts, these stores were “a great convenience to residents” as they supplied “an abundance of the necessaries of life,” according to the Lebanon Daily News.

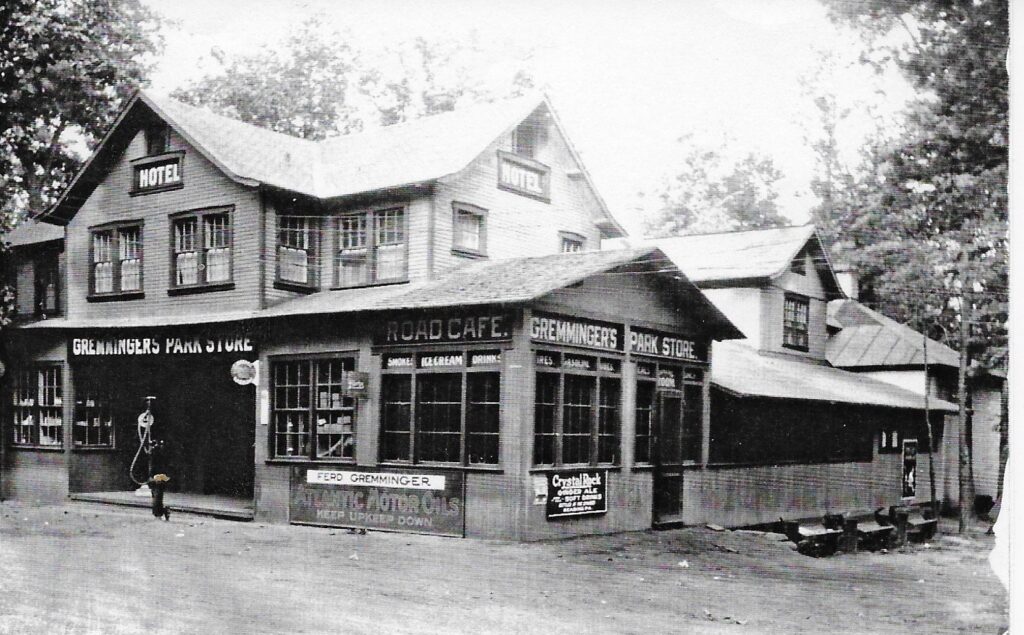

Dissinger & Lesher leased the park until 1912 when Dissinger became the sole manager. Either he or his brother, E.R. Dissinger, operated the park for several more years at which time the “park privileges” were sold to Ferdinand Gremminger, a Swiss émigré who had settled in Lebanon in 1906.

Sometimes called “Fred,” “Ferd,” and “Freddie,” Gremminger was well-known in Lebanon as proprietor of the Casino bowling alleys in the basement of the Mann Building on Cumberland Street. Even before he purchased the park privileges in March 1915, Gremminger had operated several attractions at Mount Gretna Park including a branch of his Lebanon business.

Read More: The Mann Building has stayed true to its historic purpose as a business hub

Designed to “meet the desires of the sportsman,” the Casino offered billiard tables, cigar stand and dormitory to “accommodate gentlemen that desire to spend the night on the grounds,” according to the Lebanon Daily News, which lauded the park attractions as a “step in the direction of progress for followers of sport….”

After becoming the new lessee, Gremminger pledged to “develop the park in a manner never known before,” according to the March 22, 1915, Lebanon Daily News. Besides opening a news stand, he relocated a Cumberland Street barber shop to the park.

Perhaps the most surprising of his intentions was to bring to the park what could well be a forerunner of today’s urgent care — namely, an emergency drug store.

Missing, lost, or transformed

While the map places the bakery (#19) and barber shop (#2), no reference exists for that emergency drug store. Perhaps this was #36 or #38, both of which were drawn on the map but are missing in the “References.”

Some of the numbered references have present-day iterations like the skee ball gallery (#9). Invented in 1908, skee ball was initially played on 32-foot alleys. Contests and competitions were held frequently and with spectators. Mount Gretna had its own teams and in one contest, featured a “lady roll[ing] on the Mt. Gretna team against a man,” according to the Lebanon Daily News.

“Shootting chutes” (#24) is not pictured on the map but likely is a variation of shoot the chute, invented in 1884 and with recognizable counterparts in amusement parks today. The original shoot ride involved greased tracks and flat-bottomed boats that would slide down the track and into a body of water, splashing, and soaking occupants.

Others, like hoopla (#34), don’t even appear in history books.

Among the numbered references are several — diving pier (#35), diving post (#27), boat landing (#23) — that suggest they were located at Lake Conewago, but none of them appear on the map. Nor does the bath house (#26).

Despite its name, the ocean wave (#7) is not at the lake. A July 1916 Lebanon Daily News story mentions this attraction has been added to the grounds with the caveat that “it must be seen to get a correct idea as to what is really is and does.”

The description suggests swings attached to a revolving center socket with the up-and-down motion of ocean waves. But that description also might fit the circle wave (#33).

It is possible that a pirate ship-style ride was the ocean or circle wave. Debuting in 1897 in amusement parks across the country, this attraction involved a vessel-like contraption that swung back and forth like a pendulum.

Anyone familiar with Mount Gretna will recognize #14 identified as the exhibition building. Also called the “park auditorium,” this roofed structure could seat from 3,500 to 6,000, depending on the news source. Coleman had it built for the Farmers’ Encampment, which used it for meetings before converting it to an exhibition building.

Origin of the map

Nothing is known about who drew and labeled the 30” by 36” map and what prompted its creation. Both the Lebanon County and Mount Gretna Area historical societies have copies of the map that likely started as a blueprint.

Although the map is titled “Cornwall and Lebanon Property Map,” the three tracts likely belonged to Anne Coleman Rogers, sister to Robert H. Coleman, who started the C&L Railroad and who developed the park and Lake Conewago.

Read More: Who knew? Anne of Cornwall (Part 1)

Both were part of the Colebrook Estate, estimated to have included at one time about 5,000 acres. This estate seemed to have been deeded to Anne. Robert managed his sister’s financial affairs and served as trustee of Anne’s real estate and personal holdings.

Parcels of that estate became the park in 1884. A larger portion became the training grounds of the Pennsylvania National Guard in 1885. The Pennsylvania Chautauqua and the Mount Gretna Campmeeting Association took a slice as well.

In 1903, Anne Rogers had the trust voided, and she became sole owner of the remaining Mount Gretna real estate. Given that Dissinger & Lesher held the “park privileges,” it seems unlikely that Anne Coleman Rogers was ever involved in managing the park.

When Gremminger bought those privileges in 1915, he built on his experience in Lebanon managing the Casino bowling alleys which included running competitions and tournaments, which he often competed in — and won. In many ways, the Casino was a social club with smoking rooms and soda fountain. It was open to both men and women, who had special times and events apart from those for men.

One of Gremmingers’ first moves at Mount Gretna Park was to promote the pool and billiard tables, bowling alleys and smoking rooms by relocating them closer to the paths. He also enlarged the store, built a hotel on its second floor, and renovated the bakery and café.

What Gremminger might have added to the park in 1916 was derailed on April 24, when he was shot by a man who had been thrown out of the Lebanon Casino because “of a liquor inflamed brain,” according to the Lebanon Daily News.

For days, Gremminger’s condition and prognosis were front page news. Although he underwent surgery, physicians couldn’t find the bullet fired into his abdomen, so he didn’t fully recover, which seemingly curtailed further park renovations that year.

Gremminger spent the summer confined to his bed in his cottage at the park, according to news reports, although no cottage appears on the 1916 map. Perhaps he recuperated in the boarding house that Dissinger & Lesher had built for park workers. In any case, in September, Gremminger traveled to a Philadelphia hospital where the bullet was successfully removed.

Three months later, negotiations between Anne Coleman Rogers and Gremminger began for the sale of the property. In a front-page headline on April 5, 1917, the Lebanon Daily News declared, “Mt. Gretna Park, Purchased by Ferd Gremminger, To be Made Ideal Summer Resort.”

He paid $27,000 for the tracts pictured on the 1916 map: Mt. Gretna Park, Lake Conewago (both in Tract 1), 25 acres north of the station (Tract 2) and 35 acres leased to the Brownstone Company (Tract 3).

On the day the sale was announced, Gremminger shared his plans for the park — a new bathing beach at the lake, parking for 500 cars, rifle shooting, boxing exhibitions, and roller skating. His intention, according to newspapers, was “to make Gretna one of the most desirable and favored picnic resorts in this region.”

Park remains

While most of the park’s attractions have been torn down or displaced by new technologies, two of Robert Coleman’s original features continue to draw people to Mount Gretna.

One of those is Lake Conewago, initially built for boating and eventually offering swimming with a bath house, refreshment stand and water amusements. Those continue to attract both Gretna residents and visitors.

Read More: [Photo Story] Cooling off with a trip to the Mt. Gretna Lake & Beach

The other is the park auditorium built in 1890 and today the Mount Gretna Roller Rink. It’s said that generations of children who learned to skate at the rink frequently return as adults bringing their own children.

Coleman didn’t set out to devise timeless amusements: he wanted a go-to destination to increase passenger revenues for his railroad.

But he inadvertently tapped into what seems to transcend not just crazes and fads but also centuries – the enduring allure of simple pleasures.

Questions about this story? Suggestions for a future LebTown article? Reach our newsroom using this contact form and we’ll do our best to get back to you.

Be part of Lebanon County’s story.

Cancel anytime.

Monthly Subscription

🌟 Annual Subscription

- Still no paywall!

- Fewer ads

- Exclusive events and emails

- All monthly benefits

- Most popular option

- Make a bigger impact

Already a member? Log in here to hide these messages

Quality local news takes time and resources. While LebTown is free to read, we rely on reader support to sustain our in-depth coverage of Lebanon County. Become a monthly or annual member to help us expand our reporting, or support our work with a one-time contribution. Cancel anytime.

Questions about this story? Suggestions for a future LebTown article? Reach our newsroom using this contact form and we’ll do our best to get back to you.

Be part of Lebanon County’s story.

Cancel anytime.

Monthly Subscription

🌟 Annual Subscription

- Still no paywall!

- Fewer ads

- Exclusive events and emails

- All monthly benefits

- Most popular option

- Make a bigger impact

Already a member? Log in here to hide these messages

Quality local news takes time and resources. While LebTown is free to read, we rely on reader support to sustain our in-depth coverage of Lebanon County. Become a monthly or annual member to help us expand our reporting, or support our work with a one-time contribution. Cancel anytime.