Cornwall Borough resident Bruce Chadbourne moved to Cornwall Manor a few years ago after his retirement, drawn by the history of the mine and the Cornwall Iron Furnace. He has taken to writing a few historical articles, which he’s kindly shared with LebTown for our readers to enjoy in a semi-regular series titled, “Who knew?” We hope you enjoy.

Part one: A tale of two railroads

Iconic /īˈkänik/

A word overused in today’s media-centric world but apt description of the tokens from the board game many of us grew up with. The Reading and Pennsylvania railroads, along with the Short Line and B&O (Baltimore & Ohio), were real railroads that Robert Coleman grew up with. Railroad competition was a serious matter; in the following episode, a near outbreak of war in 1887 erupted between two competing lines.

The Reading, which began in the 1830s, and the Pennsylvania, starting in the 1840s, crisscrossed Pennsylvania and neighboring states. Chartered in 1833, the “Philadelphia and Reading” served a regional purpose bringing coal from Pottstown down the Schuylkill back to the cities. The portion that served Lebanon remains an active line today, still running east-west through the middle of Lebanon out to Harrisburg.

The state chartered the Pennsylvania Railroad in 1846 connecting Harrisburg to Pittsburgh, in part to compete with the Erie Canal up north, which had opened the Great Lakes to the Hudson River. The Pennsylvania railroad would eventually connect as far west as Michigan, Chicago, and St. Louis.

The Colemans were shipping their iron (and receiving their coal) via the north on the Reading, just as decades before they had hauled it up the plank road from Cornwall to the Union Canal. In 1880, in direct competition with the existing local Cornwall Railroad, Robert H. Coleman saw the need to move iron efficiently to the southwest as well and planned a connector from Lebanon to Elizabethtown to connect with the Pennsylvania Railroad and points west.

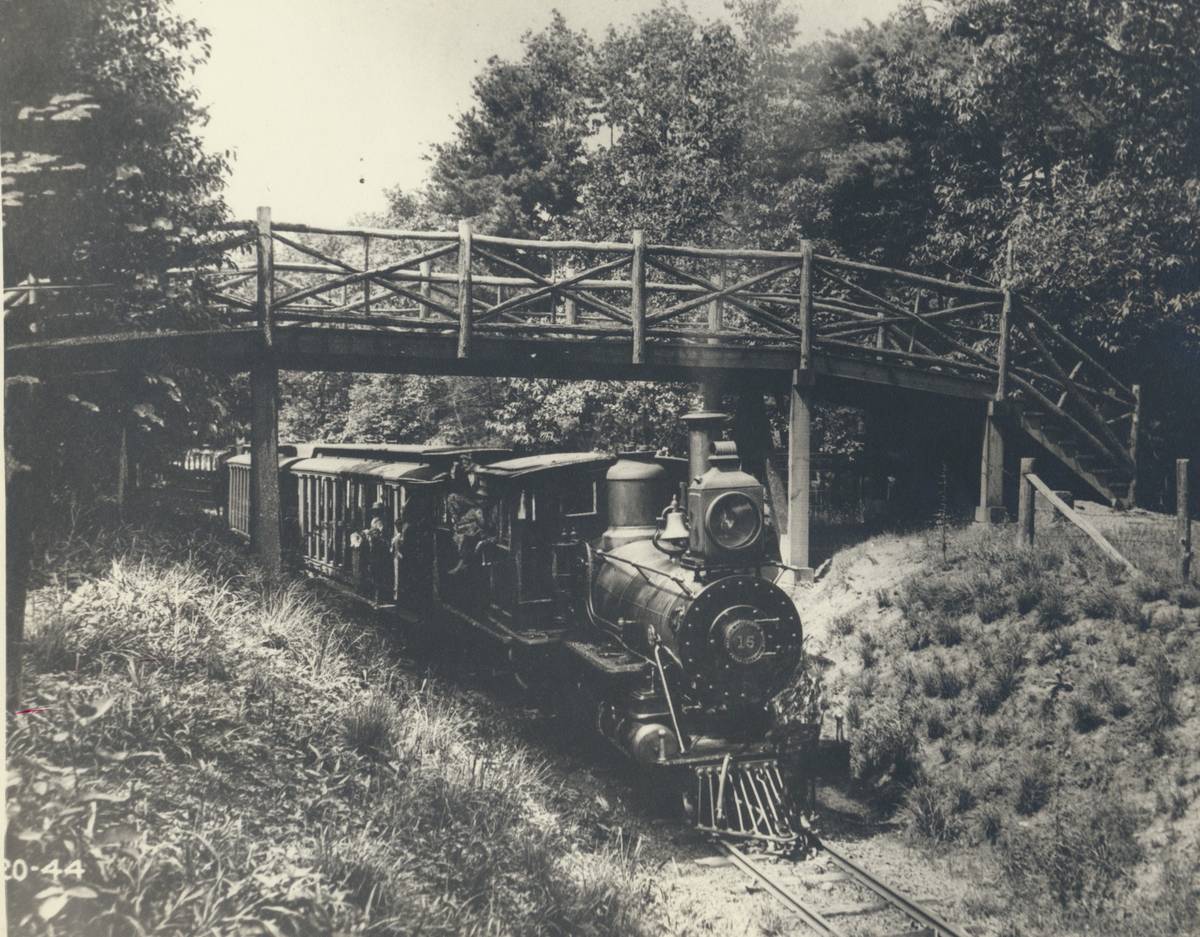

He had tried to buy out his aunts’ interest in the Cornwall Railroad but they refused. The accounts of the history vary but the competition between Coleman’s Cornwall & Lebanon Railroad (C&LRR) and his cousin William Freeman’s Cornwall line was legendary, including high-speed locomotive races and fights over maintenance of track junctions. Coleman finally built the prominent iron bridge that still stands over the tiny Cornwall center to allow his railroad to proceed unhindered southwest to Mount Gretna and beyond.

Read More: When Robert Coleman’s two-foot railway snaked through the hills of Mount Gretna

Read More: How a railroad rivalry spurred the creation of Penryn Park, Cornwall’s answer to Mount Gretna

Read More: LebTowns: North Cornwall & Karinchville

Cornwall center sported therefore not one but two competing rail stations in close proximity. In addition to rail service, they provided telegraph services – a telegram to most places cost 25 cents. Each also had its own competing delivery services, akin to our modern UPS and FedEx parcel services. If you wanted something shipped out of town on Coleman’s C&LRR you paid the agent of “Adams Express Company,” or with the Cornwall Railroad it was the “United States Express Company.” A small package sent to Washington, D.C., Philadelphia, or New York cost less than 50 cents; you might run a tab and settle up at the end of the month. If you ordered clothing or other items from New York or Philadelphia, that merchant would send it by rail using the express company; you would pay the freight upon receipt, or sometimes the entire price of the item, “cash on delivery (COD).” The U.S. Post Office was in the Cornwall station.

In other words, railroads were a tidy and essential business, one more way for Cornwall’s wealthy family to diversify and support their iron and farming businesses. Mount Gretna historians are also quite familiar with this story, as Robert H. Coleman ran his railroad through his southern hills he built one of the stops near the intersection of Pinch Road, imagining a pleasant wooded recreation area, another commercial use of his railroad. By spring of 1884 it was common for groups such as church Sunday schools and Lebanon High alumni to travel there on the new railroad for relaxing picnics.

Read More: Before the Pennsylvania Farm Show, there was the Mount Gretna Farmers’ Encampment

Part two: The scene

Though the Pennsylvania National Guard had first used the location known as Camp Hancock for an encampment in 1885, the week-long encampment of 1887 was a grand affair, drawing 8,000 troops, 438 horses, many senior officers and dignitaries (including Lt. Gen. Philip Sheridan), and newly elected Pennsylvania Governor James Beaver, himself a four-times wounded Civil War hero.

The commonwealth of Pennsylvania was grateful to Robert H. Coleman for rolling out the red carpet for the event at a personal expense of about $60,000 (just under $2 million in today’s dollars) and permitting free use of the land. The encampment still cost the state $125,000, representing a savings of $20,000 over the previous year. Coleman had also offered the state reduced transportation cost for the troops at 2 cents per mile, round trip. He had also borne the cost of erecting infrastructure including a 1,600-yard infantry range with permanent targets. But Coleman profited in other ways.

He directed his personal secretary B.F. Hean, also a Civil war veteran, to negotiate contracts to supply provisions to the state, shipped by his Adams Express Co. (which opened an office at the encampment). Some 5,000 quarts of milk were distributed each day, contracted from Lebanon county farmer Aaron Brubaker (“all the cows in Lebanon county will be taxed to their uttermost capacity” reported the Philadelphia Times). 40,000 pounds of fresh beef were shipped from Chicago, as well as a trainload of local potatoes, and onions, white beans, and tomatoes. Also, 8,000 loaves of fresh bread (per day), 18,000 pounds of hard-tack and 4,300 pounds of coffee beans and 7,900 pounds of sugar. Lebanon County furthermore provided 15,000 candles and other supplies.

Of course the horses had to eat, too; there were 50,000 pounds of hay and 56,000 pounds of oats.

Tons of shot and shell were stacked next to Coleman’s railroad tracks.

The encampment spanned the week of Aug. 7, with some initial set up in the days preceding. In addition to the thousands of troops, even greater numbers of civilians showed up beginning on the first weekend. Even today Mount Gretna sports a population of about 200 to 2000 people depending on when you count them. On that Sunday in 1887, 20,000 spectators showed up on Mount Gretna’s grounds. The numbers swelled further to 35,000 within a few days. A one-way ticket from Lebanon to Cornwall cost about a dime, a bit more to Mount Gretna, good money for the railroad’s proprietor.

Read More: Upcoming dedication of Soldiers Field to recognize Mt. Gretna’s military past

With the Civil War a recent memory of 20 to 25 years, the spectacle of thousands of troops parading, marching, drilling, practice shooting rifles and cannon, and engaging in mock battles drew the throngs. They needed to eat as well.

The troops were warned to avoid the “picnic atmosphere” of Mount Gretna afforded by so many spectators. There were plenty of peddlers and hawkers drawn to the spectacle. Consequently beer and liquor were found among the soldiers, some of it smuggled inside a barrel of vegetables, until the officers rid the camp of it. To discourage the soldiers’ access to liquor and women, barbed wire was erected to separate Camp Hancock from Mount Gretna.

With the great numbers there was fear also of crooks and pick-pockets and so a force of Pinkerton detectives were sent for. (Editor’s note: A year later, Robert Coleman sought the help of the Pinkerton agency for a problem at his own stable. Find our previous stories about the Pinkerton Cornwall Caper here.)

Part three: Did someone mention a riot… in Cornwall?

Overall the encampment was a great success, to be repeated in subsequent years, with visits by noted dignitaries and great coverage by the newspapers from Harrisburg, Reading, Philadelphia, and points beyond. However the onset of the encampment was another story, which threatened the outcome of the entire affair.

An advance guard of several hundred men and supplies under the command of General Townsend left Philadelphia by train at 7 o’clock Thursday morning, Aug. 4.

“At Bridgeport, Pottstown, Phoenixville, Reading and Lebanon big crowds gathered to see the soldier boys,” said one newspaper. “All along the line men left their work in the big iron foundries to watch the train. Girls in the factories waved their handkerchiefs, aprons and sun bonnets.”

The men were to arrive at Mount Gretna by 11 o’clock but it wasn’t until six hours later that they started trickling into camp … on foot.

What the papers referred to for several succeeding days as “the Railroad War at Cornwall,” began as Townsend’s train approached Lebanon. The local Cornwall Railroad was allied with the (Philadelphia and) Reading and the local Cornwall & Lebanon partnered with the Pennsylvania. Per previous agreement, the Reading train was to stop in Lebanon and transfer its cargo to Coleman’s railroad, the Cornwall & Lebanon line, for the trip to Mount Gretna. However, a previous contract with the Reading Railroad specified carrying passengers to Cornwall on the Cornwall Railroad. The conductor therefore allowed the train to proceed on to Cornwall on the wrong line.

On arrival in Cornwall, the train stopped as the Cornwall Railroad does not go to Mount Gretna but to points south. Townsend’s seemingly reasonable solution was to disembark the men and material in Cornwall and transfer them to a train, assuming one became available, on the adjacent Cornwall & Lebanon line, a distance of 10 feet. Superintendent Irish, of Coleman’s railroad refused this at Coleman’s instructions. He insisted that the train of at least 10 cars (carrying men, gun trucks, caissons and baggage) be backed up to Lebanon to the C&L station and put on the proper track.

Coleman stuck to his proverbial guns and eventually won the war, but for six hours the train sat in Cornwall, and not quietly.

Several soldiers in the detail were train engineers and attempted to switch the train onto the C&L track until they were warned off by a monkey wrench-wielding engineer of the Reading railroad, warning them “keep off my train!” Word of the conflict spread publicly and crowds of spectators flocked to Cornwall to see what the troops were going to do.

Townsend telegraphed word to his superiors already in Mount Gretna asking “shall I take the train by force and proceed on?” There erupted a dissent among senior officers at Gretna, one saying “No,” but another insisting the National Guard had a right to take forceable possession. When the trainmen heard of this they uncoupled their engine from the train and moved it off to safety, parking it on the local turntable.

Brigadier General Gobin, upset that his battery was being held up, threatened he would get his equipment to camp “if he had to shell the county.” As it turns out, of course no shots were fired and they didn’t get to camp until 10 o’clock that evening after a dead march of five miles over a rough mountainous road.

Meanwhile Coleman’s trains to Mount Gretna continued running all day through Cornwall on the C&L line. Superintendent Irish issued orders not to sell tickets to men in uniform and the trainmen were ordered to put off any soldier who attempted to board the train. “There was a scene of wild confusion every time a train came along for Mt. Gretna,” reported the Philadelphia Times. Only one man succeeded, an officer surgeon of the First Brigade.

When this officer reported to his superiors in Mount Gretna they began telegraphing to management of the Reading railroad, who then contacted Superintendent Neff of the Cornwall Railroad, to back the train up to Lebanon and break the standoff. This time Neff refused; he had done what he had been contracted and paid to do.

The men were frustrated, hungry, and tired, and considered taking action of their own until Brigadier General Snowden ordered them from the train and to march to camp. Imagine several hundred soldiers marching what is now the Lebanon Valley Rail Trail from Cornwall to Mount Gretna. These days some of us have done it on foot, but mostly on bicycles. They didn’t have macadam pavement or smooth cinders to walk on, and with their equipment – it was a railroad bed, with wooden ties and slag ballast underfoot.

Off they straggled. The first arrivals reached camp about 6 o’clock in the evening. A few had broken into one of the railroad’s tool houses, stole a hand-car and about 25 men propelled themselves to camp up a heavy grade, only later to be disciplined for the theft.

The Philadelphia paper reported: “Among the country people there is a good deal of excitement over today’s lively scenes. Both railroads claim that they have won the fight.” At 5 p.m. the Reading railroad manager was still meeting in Lebanon with one of the generals to get the train moving.

Once the troubles of Thursday evening settled down, preparations at Camp Hancock resumed and throughout the weekend and ensuring week, the newspapers wrote glowing stories of the parades and events of the encampment. The Patriot of Harrisburg on Saturday wrote “the settlement of the railroad war is regarded as a victory for Mr. Coleman, as all the soldiers will now be carried over his road from Lebanon.” All’s well for them but the issue remained that excursion tickets for the general public sold by the Reading railroad to Cornwall will leave them facing the same long hike that the soldiers had taken to the encampment; Mr. Coleman insisted he will only accept through traffic from those who boarded his train in Lebanon. To ensure that passengers did not transfer from the Cornwall Railroad in Cornwall to his Mount Gretna train, a high fence had been hastily erected on Friday, separating the two railroads.

The newspaper feared the reaction of those of the public on Sunday morning “who have not kept themselves posted” of the day’s conflict. Nevertheless at least 20,000 spectators arrived in Mount Gretna for the events of the day, and all seemed forgotten.

According to the accounts Coleman was present most days of the encampment. On Wednesday he and his wife attended formal ceremonies, sitting next to General Sheridan along with Generals (Gov.) Beaver and Hartranft. Coleman was widely recognized and respected not only as host of the encampment but for his reputation as the millionaire businessman who continued to bring prosperity to Lebanon.

In a final anecdote, he had driven up to visit the Governor for the afternoon, and a young sentinel named Samuel Wright was ordered to hold Coleman’s horse. Having sheathed his sabre he took hold of the horse’s bridle and stood at attention in the sunlight for two hours. Later, Coleman readied to leave, tossing a silver quarter to the sentinel “supposing him an ordinary orderly.” The story got around headquarters quickly, earning Wright some uncomfortable attention, but he got to keep the quarter “as a souvenir of the first money he ever earned.”

Of late the residents of Lebanon County have been intrigued by the ground-shaking booms of the National Guard artillery at Fort Indiantown Gap. May these echoes remind us of the ghosts of the General who would have shelled this county and the war between two railroads which are no more.

The author credits contemporary coverage by a number of newspapers for being instrumental in putting together this narrative, including The Scranton Truth, The Reading Times, The Philadelphia Times, Philadelphia Record, and The Patriot.

Any questions about the 1887 Cornwall riot we left unanswered? Ideas for future history stories? Let us know here.

Do you want to read more stories like this?

If you want to see LebTown continue and expand its history reporting, consider joining LebTown as a member. Your support will go directly towards stories like this and you will be helping ensure that our community has a reliable news source for years to come.

Learn more about membership and join now here.